Venture capitalists last month sunk nearly half a billion dollars into a Southern California defense technology startup whose surveillance towers track migrants along the U.S.-Mexico border.

Anduril Industries, the Irvine-based maker of autonomous drones, towers and small ground sensors, will use the $450 million for acquisitions and build out its AI-powered tech designed for military and border enforcement agencies.

But activists and experts are raising flags about the technology, pointing to privacy violations and civil liberties infringements.

They also question the government's steep investment in the private defense contractors behind it.

"The fact that we're spending money on the border wall also means that we're not investing in the things we all actually need here in the valley," said Norma Herrera, an organizer with the Rio Grande Valley Equal Voice Network.

She pushes back against what President Biden called an "effective and modern border security" system—a bureaucratic apparatus that allocates $1.2 billion for border infrastructure next year (still a drop in the bucket, given the Department of Homeland Security's $52 billion 2022 budget).

Before the pandemic, Herrera knocked on doors in Texas' Starr County to tell residents about the amount of money elected officials were pouring into Trump's border wall. Now, she's learning how to explain the virtual wall, one that's often harder to notice.

Anduril declined to make executives at the company available for interviews.

Surveillance on the Border

Over the last decade, the border security and immigration detention industry has ballooned as Democrats and Republicans both funnel more government money into private companies. Between the fiscal years 2017 and 2020, Customs and Border Protection received about $743 million from Congress for tech and surveillance, according to the legal organization Just Futures Law. And in the 2021 fiscal year alone, the Department of Homeland Security received over $780 million for the same purpose.

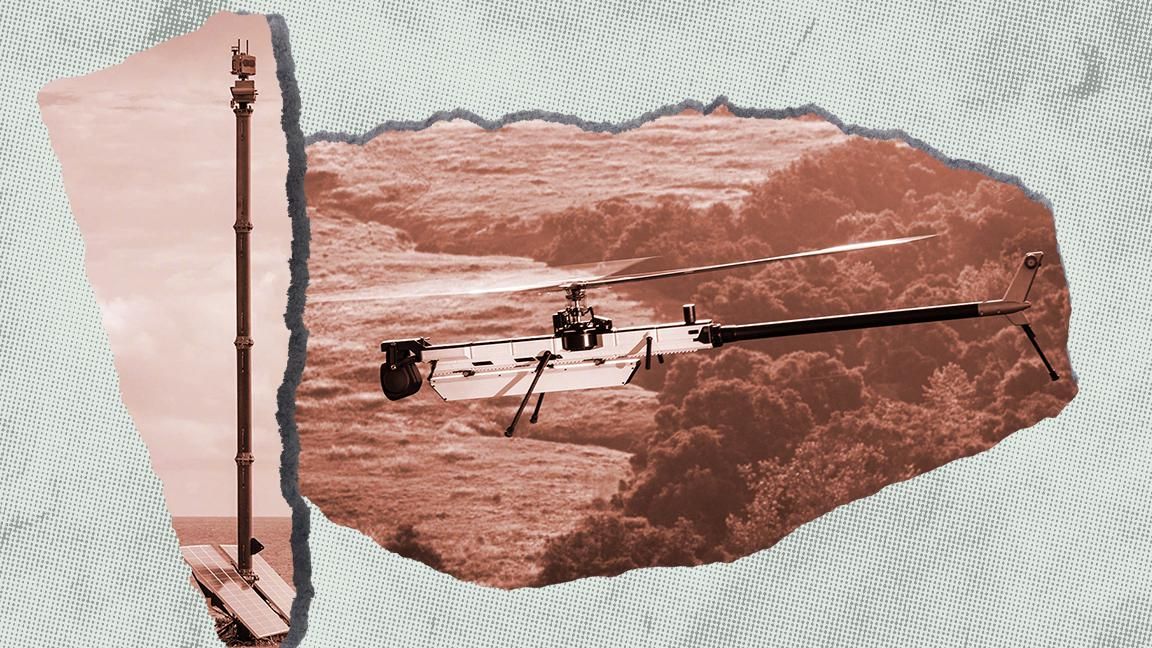

Anduril's recent project with CBP revolves around a $250 million contract signed under the Trump administration in July of 2020 to set up 200 solar-powered watch towers along the southern border. Of the towers, 60 are up and running as of July 2.

Under Biden's leadership, funding for border technology has become an even bigger priority, said Dinesh McCoy, a legal fellow at Just Futures Law.

"It's in large part a response to coinciding pressures of distinguishing themselves from the Trump years," he said.

Many Democrats back Biden's vision, considering a virtual barrier a far better alternative to the physical border wall Republicans prefer.

"When it comes to proposals for a virtual wall, we're talking about heavy, heavy investments," said Saira Hussain, an attorney at the Electronic Frontier Foundation who specializes in racial and immigrant justice, surveillance and technology.

Government agencies are tapping a number of private companies to install the technology. In 2019, CBP awarded the Israeli defense contractor Elbit Systems $26 million to install surveillance towers along the border.

Then came the administration's 2020 deal with Anduril. Its AI-powered operating system, called Lattice, is designed to distinguish humans from animals along the border and send information to an agent's cell phone. The company has to date received $691 million in venture capital, including $450 million that had backers including Andreessen Horowitz last month. Anduril is now valued at $4.6 billion.

"As with all of our investments, this is a bet not just on the technology (breathtaking) and the market (enormous) but also the people (outstanding)," Andreessen Horowitz co-founder and general partner Marc Andreessen said in a prepared statement.

Marc Andreessen is a longtime investor in Palmer Luckey, Anduril's 28-year-old founder. He backed Luckey's first company — virtual reality startup Oculus — before Facebook bought it for $2 billion in 2014. A few years later, Luckey left following reports that he was funding a far-right political group.

In 2017, Luckey opened Anduril with a band of former employees from Oculus VR and Palantir, the software giant with major contracts with several government agencies.

Eyes Everywhere

Along the border, Anduril's 33-foot towers are continuously scanning plots of land about three miles in diameter. They're built to ignore animals — what CBP calls a "false positive" — and light up after detecting movement from people or cars.

The towers are watching "illegal border crossings, human trafficking and drug smuggling," a spokesperson for Anduril said by email.

If a person or group falls out of the camera's vision, AI tells the next tower to pick it back up. Border patrol agents then receive an alert to their cell phones or computers.

The goal is to mimic an agent's pair of eyes, especially in remote and rural spots. As one agent put it, "they see what we can't see on the ground."

They also run on solar power, a feature CBP said avoids the need for new infrastructure that can "complicate the Border Patrol's agreements with many of the private ranchland owners, national parks, and Native Americans' tribal lands where the Border Patrol must work."

Video surveillance drones and towers are puncturing nearly every industry, from homeland security to fast food delivery to monitoring traffic and parking violations along busy streets.

The tech is also raising a flood of questions from academics and legal groups like the Electronic Frontier Foundation and Just Futures Law, all of them worried about the implications of surveillance not only for migrants, but for U.S. residents. In May of 2020, for example, agencies CBP flew a drone over Minneapolis to record protestors following the police murder of George Floyd.

"We know that what's often deployed at the border and what's normalized at the border in terms of surveillance eventually makes its way into the interior of the United States," said Hussain, the attorney from EFF.

The company says it does not use facial recognition or collect identifiable information.

But critics like the ACLU of Texas and other civil liberties groups said it's unclear what data is being collected by private defense contracts like Anduril and how it could be used and shared.

"The border is a testing ground for surveillance elsewhere," said McCoy, the legal fellow at Just Futures Law. "Unfortunately, it's been primarily used to surveill Black and brown folks in the U.S. and abroad."

As the U.S. begins reducing its military footprint in the Middle East, McCoy suspects other military contractors will turn to border surveillance as a new form of profit.

"These tools that were once confined to military contexts have found themselves more and more in local communities," he said.

Anduril, for its part, insists it is providing the government with a crucial security mechanism. "Anduril identifies a security problem," reads a prepared statement forwarded to dot.LA by a company spokesperson, "builds a potential solution, then takes it to the government for potential consideration."

Lead art by Ian Hurley

Editor's note: This article has been updated to clarify that Andreessen Horowitz was involved in Anduril 's$450 million raise round, but was not the sole funder. Additionally, mentions of Anduril's $250 million contract with CBP have been updated to clarify that they were not negotiated with President Trump himself, but rather with members of his administration.

- Snapchat Accused of Being an 'Ecommerce' Site for Fentanyl - dot.LA ›

- A TikTok Timeline: The Rise and Pause of a Social Video Giant - dot ... ›

- Fisker and Apple Manufacturer Foxconn to Build Electric Cars - dot.LA ›

- Oracle Confirms Deal with TikTok - dot.LA ›

- Ferret Raises $4 Million to Bring Checkered Pasts to Light - dot.LA ›

- Defense Startup Anduril Industries Seeking to Raise $500M-Plus: Report - dot.LA ›

- New Bill Aims To Regulate Use of Facial Recognition Tech - dot.LA ›

- Palmer Luckey's Anduril Introduced Its First Weapon - dot.LA ›

- LAPD Faces Criticism After Using SweepWizard - dot.LA ›

Los Angeles Chief Information Officer Ted Ross

Los Angeles Chief Information Officer Ted Ross Film director Scott Mann (left) and Robert De Niro on the set of "Heist".

Film director Scott Mann (left) and Robert De Niro on the set of "Heist".