🔦 Spotlight

Hello Los Angeles,

Despite headlines about swipe fatigue and dating app burnout, Tinder believes the problem isn’t that people are tired of dating. They’re tired of bad dating experiences.

So it felt fitting that Tinder chose the El Rey Theatre in Los Angeles, a venue known for reinvention, to make its case that the category is far from over.

Walking into the El Rey, it was clear Tinder wanted this to feel less like a tech launch and more like a cultural moment. Music was bumping, the room buzzed with chatter and excited energy, red light beams cut through the room, and chandeliers glowed overhead.

At Tinder Sparks 2026: Start Something New, Match Group and Tinder CEO Spencer Rascoff took the stage to outline what the company calls the biggest evolution of the app in years. Tinder remains the largest dating app in the world, used by tens of millions of people across more than 185 countries and responsible for billions of matches every year.

Match Group and Tinder CEO Spencer Rascoff

Match Group and Tinder CEO Spencer Rascoff

Rascoff framed the shift around a broader cultural reality. In a world where people increasingly interact with machines, technology and AI, the need for real human connection has not gone away. If anything, Tinder believes it has only grown stronger.

To respond to that shift, Tinder says it’s focusing on what it calls “sparks,” the moments when a match actually turns into a real conversation.

As Rascoff put it on stage:

“We are not optimizing for swipes or likes. We are optimizing for sparks.”

That philosophy is shaping a wave of new features discussed throughout the keynote by Tinder’s leadership team, including Mark Kantor, SVP and Head of Product, Yoel Roth, SVP of Trust & Safety, and product leaders Claire Watanabe and Hillary Paine.

Image Source: Tinder

Image Source: Tinder

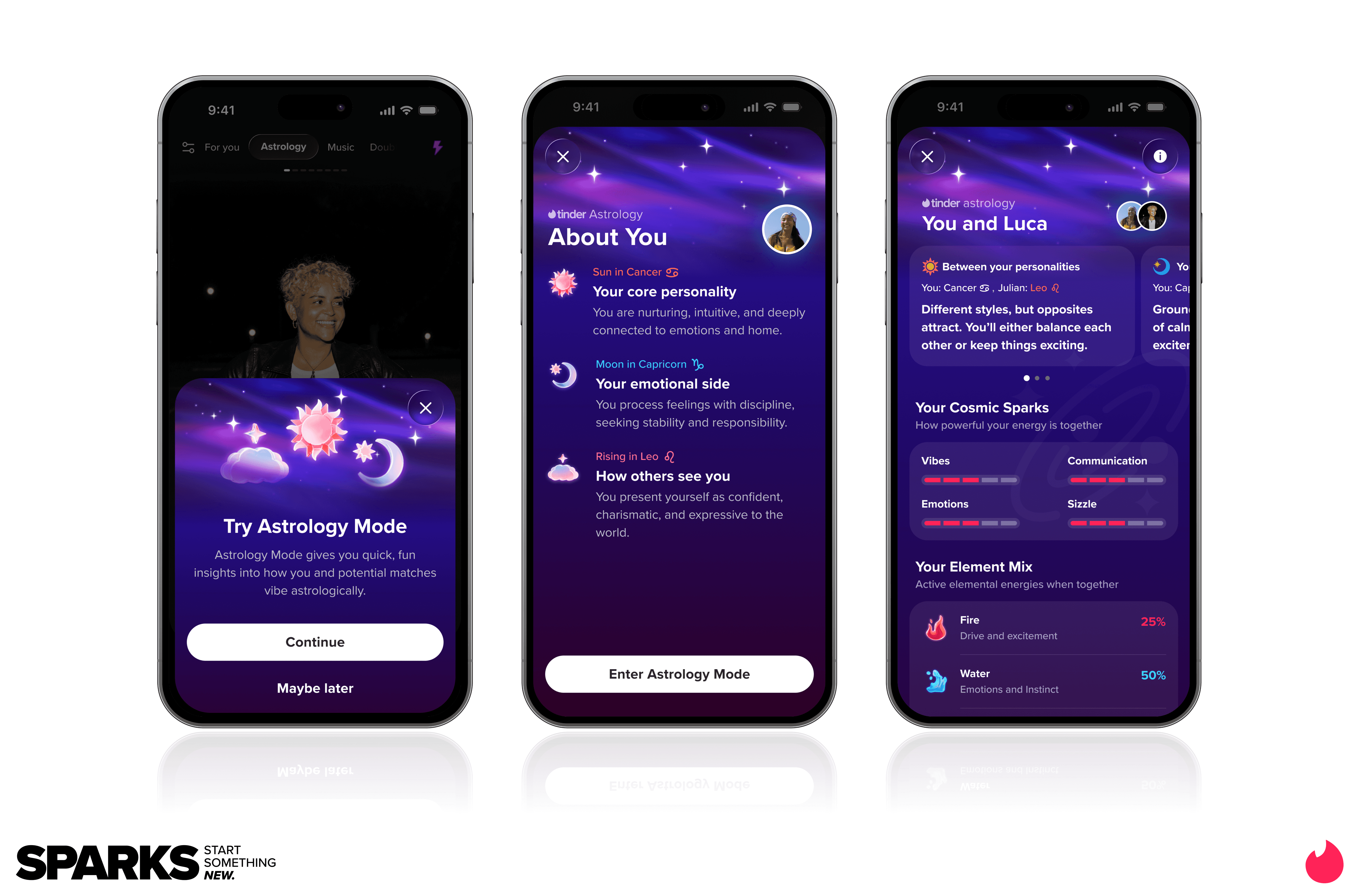

Among the updates are Music Mode, which lets users connect through shared songs and artists, and a new Astrology Mode that highlights compatibility between zodiac signs. Tinder is also leaning further into social dating with Double Date, a feature that lets friends match with other pairs together. The feature is already gaining traction with Gen Z users, reflecting a broader shift toward more social and lower-pressure ways to meet people.

Image Source: Tinder

Image Source: Tinder

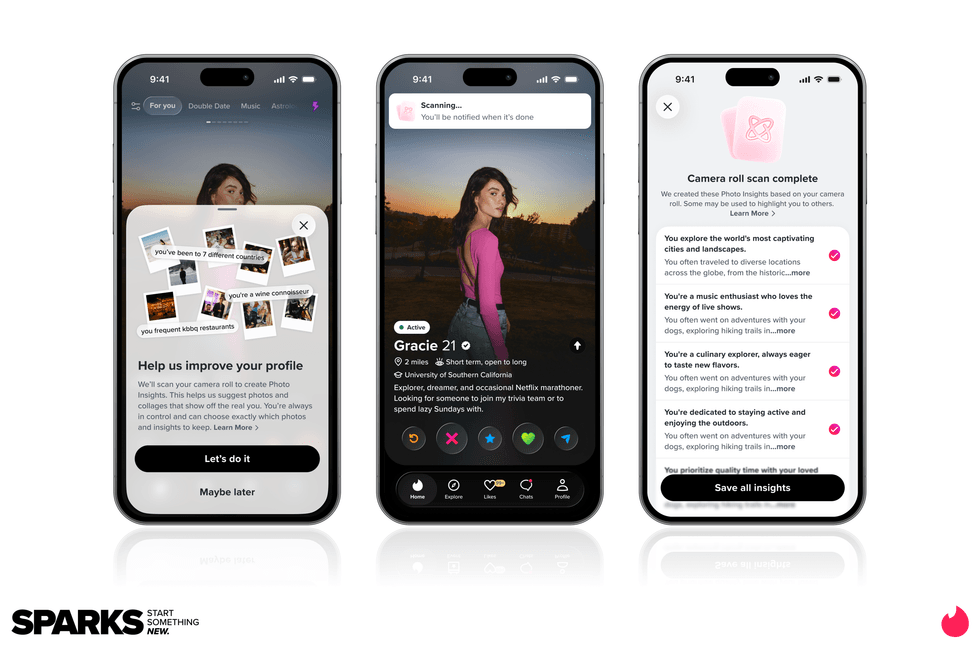

Tinder is also redesigning profiles to help users express more personality. New tools can surface stronger photos from a user’s camera roll, improve lighting, and highlight interests more visually, while integrations with platforms like Spotify, Duolingo and the restaurant app Belly bring more of a person’s real life into their profile.

Image Source: Tinder

Image Source: Tinder

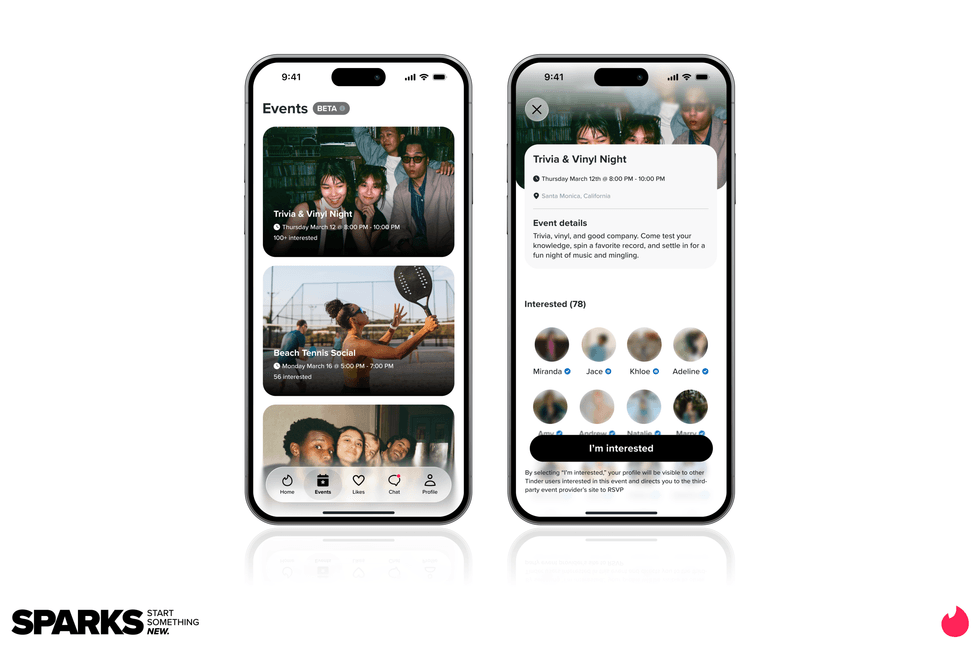

But the most interesting experiment might be happening right here in LA. Tinder is launching IRL Events in the city, letting users browse and RSVP to real-world meetups directly through the app. Think coffee shop raves, trivia nights and pickleball tournaments. The idea is simple. Dating works better when it feels like a social activity instead of an interview.

Image Source: Tinder

Image Source: Tinder

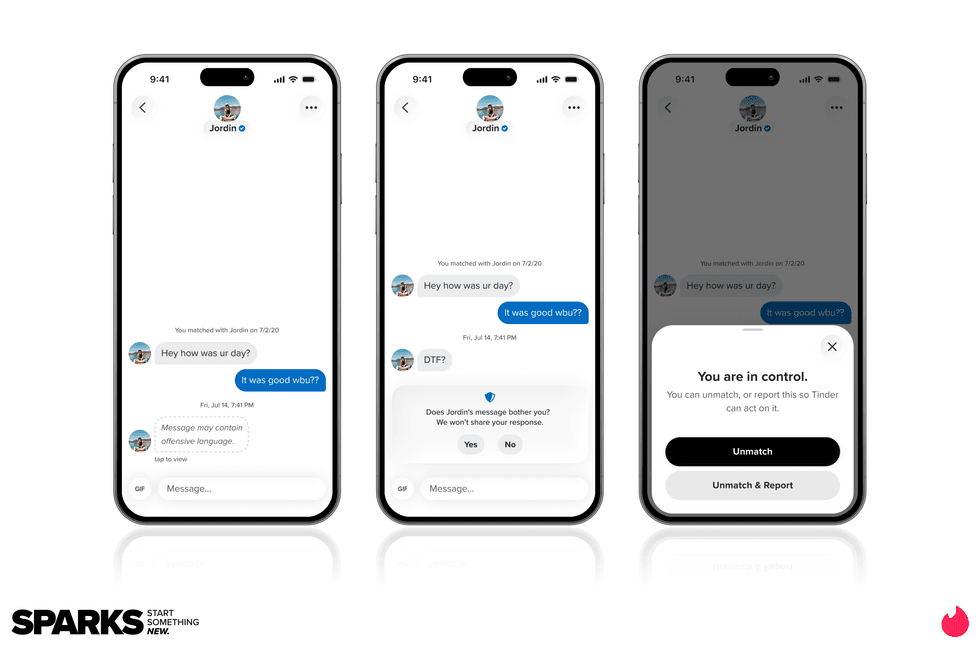

Under the hood, Tinder is also leaning more heavily on AI to improve recommendations. New tools like Learning Mode and Chemistry aim to better understand what users are actually looking for and surface stronger matches faster. At the same time, the company is investing heavily in safety, expanding Face Check, a facial verification system designed to reduce bots and impersonation accounts.

Closing out the presentation, Melissa Hobley, Tinder’s Chief Marketing Officer, zoomed out from the product roadmap to the brand’s cultural footprint, noting that Tinder is mentioned in billions of TikTok videos and has become shorthand for how younger generations talk about dating.

Taken together, the updates represent Tinder’s most significant evolution in years. And judging by the energy inside the El Rey this week, the company believes the next chapter of dating will be more social, more expressive and more intentional. It’s a shift being shaped right here in Los Angeles, and one that could redefine how the next generation meets.

Now onto this week’s LA venture deals, fund announcements and acquisitions.

🤝 Venture Deals

LA Companies

- Hurray’s GIRL BEER raised a $5M seed round led by Lakehouse Ventures, with participation from Spice Capital plus CPG insiders and entertainment executives, as it accelerates national expansion. The LA-based flavored light beer brand says it has already landed retail placements at Walmart, Kroger, Albertsons, and Whole Foods, and plans to use the new capital to deepen distribution, enter new markets, and ramp up marketing, alongside a rollout of seven new flavors. - learn more

- Freestyle closed a $10M Series A led by Silas Capital, with significant participation from ECP Growth. The company also noted continued backing from existing investors including Mucker Capital, Adapt Ventures, and Superangel, as it scales its premium diapers and wipes business following nationwide launches at Walmart and Target. - learn more

- MAX BioPharma announced a new investment and partnership with Technomark Life Sciences to advance Oxy210, its oxysterol-based, orally available drug candidate for MASH. Technomark is joining as a strategic lead investor by participating in MAX BioPharma’s $13M Series A to fund a Phase 1a/1b first-in-human study, and the companies say the collaboration will pair MAX’s therapeutic platform with Technomark’s drug development experience. - learn more

LA Venture Funds

- B Capital participated in ORO Labs’ $100M Series C, which was led by Brighton Park Capital and Growth Equity at Goldman Sachs Alternatives, as the company pushes deeper into what it calls agentic procurement orchestration. ORO said the new funding follows 300% revenue growth over the past year and will be used to speed up product development, expand go-to-market and customer teams globally, and broaden enterprise use cases across procurement, finance, legal, and supply chain workflows. - learn more

- Aliment Capital participated in Tropic’s oversubscribed $105M Series C, which was co-led by Forbion’s Bioeconomy Fund and Corteva as the company scales the commercial rollout of its gene-edited tropical crops. Tropic said the funding will help expand production of its banana portfolio, accelerate its banana and rice pipelines, and support entry into additional climate-resilient crops, following the 2025 launch of its first new banana varieties in more than 75 years and demand that is already outpacing supply. - learn more

- B Capital doubled down in Axiom’s $200M Series A, which valued the company at more than $1.6 billion and was led by Menlo Ventures. Axiom said the new funding will help it extend its lead from formal mathematics into what it calls “Verified AI,” with plans to apply its technology beyond mathematical discovery into software and hardware verification. - learn more

- WndrCo participated in Quince’s $500M Series E, a round led by ICONIQ that values the manufacturer-to-consumer retail platform at $10.1B post-money. Quince says it will use the fresh capital to accelerate growth and global expansion of its proprietary M2C operating system, which uses AI-driven demand forecasting and direct factory partnerships to cut traditional retail markups. Other investors in the round included Basis Set Ventures, Wellington Management, MarcyPen Capital Partners, Baillie Gifford, Notable Capital, and DST Global. - learn more

- Matter Venture Partners co-led Eridu’s oversubscribed Series A, part of $200M+ raised as the AI networking startup emerges from stealth to tackle what it calls the “network wall” bottleneck in AI data centers. - learn more

- Matter Venture Partners participated in Rhoda AI’s $450M Series A, backing the startup as it comes out of 18 months in stealth with FutureVision, a video-predictive control platform aimed at helping robots operate reliably in messy, real-world industrial environments. The round included a large syndicate of investors, including Capricorn Investment Group, Khosla Ventures, Leitmotif, Mayfield, Premji Invest, Prelude Ventures, Temasek, Xora, and John Doerr, and the company says the funding will accelerate development and industrial deployments. - learn more

- Halogen Ventures participated in Rasa Legal’s $5M late-seed round, backing the company’s push to scale its tech-enabled criminal record sealing and expungement service nationwide. The round was led by Rethink Education with participation from Social Finance and the Richard King Mellon Foundation, and Rasa says the funding will help it expand leadership, speed product development, and grow beyond its current footprint (Utah, Arizona, and Pennsylvania). - learn more

- Halogen Ventures participated in Nyad’s $1.3M oversubscribed pre-seed round, backing the Birmingham-based startup as it launches an AI decision-support tool for wastewater treatment operators. The round was led by Boost VC with participation from Draper Associates, Ollin Ventures, Apprentis, First Avenue Ventures, and strategic angel Troy Wallwork, and Nyad says it will use the funding to hire, grow customers, and keep building the product as retirements thin the wastewater workforce. - learn more

- MANTIS VC participated in Scanner’s $22M Series A, which was led by Sequoia Capital and also included CRV, as the company builds a high-speed security data layer for AI-driven threat investigation. Scanner said the funding comes as security teams at companies like Notion, Ramp, and BeyondTrust use its platform to search years of log data quickly and power agentic workflows that help hunt threats, triage alerts, and investigate incidents more efficiently. - learn more

- Chapter One participated in Zcash Open Development Lab’s $25M+ seed round, joining a syndicate that included Paradigm, a16z crypto, Winklevoss Capital, Coinbase Ventures, Cypherpunk Technologies, and Maelstrom. The new company, formed by former Electric Coin Company team members, said the funding will support continued development of privacy-focused infrastructure for the Zcash ecosystem, including its self-custodial wallet and broader shielded payments tooling. - learn more

- CIV participated in Isembard’s $50M Series A, which was led by Union Square Ventures and also included Tamarack Global, IQ Capital, and existing backer Notion Capital. Isembard said the new funding will help it open 25 AI-powered factories by the end of 2026, expand its engineering team, and enter Germany, France, and Ukraine as it scales software-driven component manufacturing for aerospace and defense customers. - learn more

- WndrCo participated in Crafting’s $5.5M seed round, which was led by Mischief as the startup launched general availability for Crafting for Agents. The company said the new capital will support its push to become core infrastructure for AI-driven engineering teams, giving agents secure access to production-like environments so they can validate, test, and ship code inside complex enterprise systems used by customers including Brex, Faire, and Webflow. - learn more

LA Exits

- Hireguide has been acquired by HireVue, which is buying Hireguide’s underlying technology and bringing the Hireguide team into HireVue’s product org. HireVue says the deal accelerates its agentic AI roadmap, starting with a voice-based AI interviewer designed to help employers qualify candidates earlier and run smarter, more conversational hiring workflows. - learn more

- Ultracor has been acquired by Applied Aerospace & Defense, bringing the California-based maker of specialized honeycomb core materials into Applied’s advanced composites platform. Applied says the deal supports its selective vertical integration strategy by strengthening supply chain control and boosting speed and capacity for space and defense programs, from satellites and missiles to antennas, radomes, and next-gen aircraft. - learn more

Download the dot.LA App

Match Group and Tinder CEO Spencer Rascoff

Match Group and Tinder CEO Spencer Rascoff Image Source: Tinder

Image Source: Tinder Image Source: Tinder

Image Source: Tinder Image Source: Tinder

Image Source: Tinder Image Source: Tinder

Image Source: Tinder

Image Source: Revel

Image Source: Revel