‘Every Shopper Will Be a Seller’: Tradesy Founder Tracy DiNunzio Talks Vestiaire Collective Merger

When Tracy DiNunzio had the idea to build a secondhand high-end apparel company, she bootstrapped the business by renting out her bedroom on Airbnb and sleeping on her living room couch.

It worked. Over the past decade, Tradesy—the Los Angeles-based, peer-to-peer secondhand clothing platform that DiNunzio built—gained 7 million members and hauled more than $145 million in venture capital funding. DiNunzio reclaimed her bedroom. And last week, the company announced it would be acquired by Paris-based Vestiaire Collective, another peer-to-peer luxury clothing marketplace.

“There are a lot of companies in fashion resale, but we're not really competing with each other so much as trying to change consumer behavior and compete with retail,” DiNunzio told dot.LA.

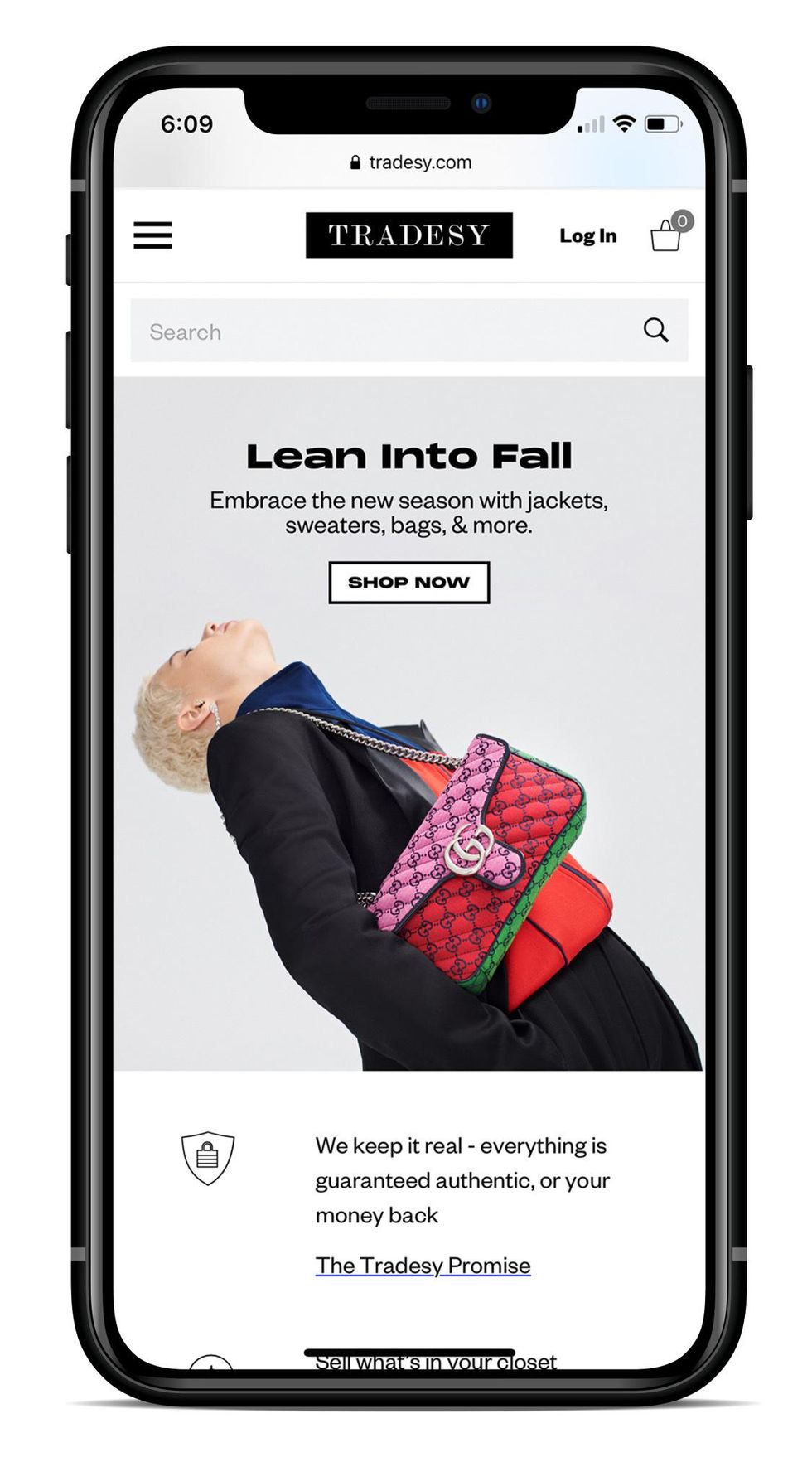

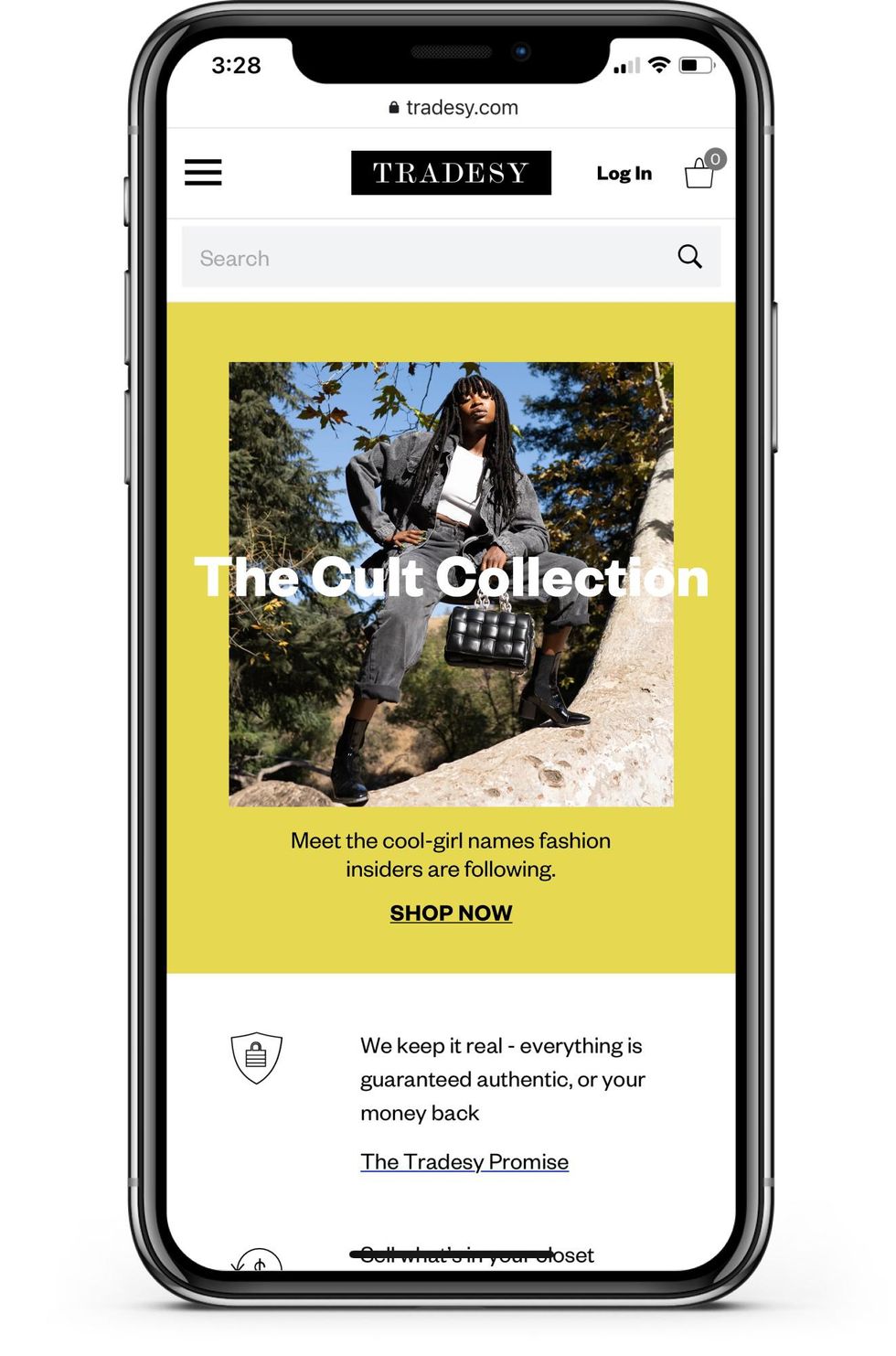

Image courtesy of Tradesy

Together, Tradesy and Vestiaire Collective boast 23 million customers and a catalog of some 5 million fashion items valued at more than $1 billion. The U.S. has quickly become Vestiaire Collective’s largest market, and the company is using the Tradesy merger to lay new roots in the States—with plans for a new authentication center as well as a technology hub, both located in Los Angeles. DiNunzio will serve as CEO of the combined company’s U.S. operations. (Financial terms of the deal were not disclosed.)

The acquisition feels logical given the parallels between the two companies. Both were launched in 2009 by women entrepreneurs. (Vestiaire Collective was founded by Fanny Moizant and Sophie Hersan; Moizant will serve as president of the combined company, while Vestiaire Collective chief executive Maximilian Bittner will remain CEO.). Both sought to compete in a market then dominated by eBay and brick-and-mortar consignment shops, which paid sellers a fraction of the profits they were making. And both adopted a peer-to-peer model by which users can sell and buy luxury goods through their websites.

The secondhand clothing market is expected to grow to $64 billion by 2028, according to CB Insights, driven in part by similar companies like Poshmark, The RealReal, Mercari and FarFetch. These companies are seeing rapid growth, and Tradesy and Vestiaire Collective are far from the only ones consolidating: ecommerce marketplace Etsy acquired secondhand apparel platform Depop for more than $1.6 billion last year.

But resale apps like Tradesy still have a long way to go before eclipsing retail. Buying secondhand clothing online is a less consistent experience than buying from a retailer, as even the most devoted of eBay shoppers will attest. The lack of quality control, along with unpredictable shipping and unscrupulous scammers, can make for an inconsistent experience.

On the sellers’ end, uploading photos, writing descriptions and pricing out items can quickly become a full-time job. When buyers complain about purchases—whether their claim is legitimate or not—it will usually result in a refund directly out of the seller’s wallet.

“Every shopper will be a seller in the future, but it has to be easy and it has to be seamless,” DiNunzio said. “The reason that every single person isn't selling every single thing they're no longer wearing today is because it's not easy enough yet.”

As middlemen, both Vestiaire Collective and Tradesy need to be able to organize millions of unique items that are described and priced in different ways—a task as logistically challenging as it sounds. In response, the company plans to automate parts of the authentication process through its L.A. technology hub, which will complement the new authentication center in the city (Vestiaire Collective’s second authentication center in the U.S. and fifth globally).

Much like startups Rent The Runway and L.A.-based Rent-a-Romper (both of which focus on short-term apparel rentals), Tradesy and Vestiaire are part of a growing number of fashion platforms invested in the “circular economy.” The concept is rooted in offsetting the damage that “fast fashion” has had on the environment by focusing on resale, repairs and rentals.

“I think we'll see kind of a whole different concept of ownership, where everything you own is sellable whenever you're done with it,” DiNunzio said. “That seems like a better way for us to consume things, and it would naturally lead to people buying higher quality things that last so that they can resell them. And that creates less waste, less disposable products in the market and ultimately gets us closer to having commerce overall be more sustainable over the years."