A New Study Breaks Down Just How Badly COVID-19 Hit Minority-Owned Businesses

Sam primarily covers entertainment and media for dot.LA. Previously he was Marjorie Deane Fellow at The Economist, where he wrote for the business and finance sections of the print edition. He has also worked at the XPRIZE Foundation, U.S. Government Accountability Office, KCRW, and MLB Advanced Media (now Disney Streaming Services). He holds an MBA from UCLA Anderson, an MPP from UCLA Luskin and a BA in History from University of Michigan. Email him at samblake@dot.LA and find him on Twitter @hisamblake

A new study quantifying the impact of COVID-19 on American small businesses confirms what many have suspected. Black small business owners have been ravaged by the pandemic. They were nearly twice as likely to have shut down in the last several months compared to the national average. Latinx, immigrant and female owners have also fared poorly.

The research, published this week in a working paper by the National Bureau of Economic Research, examines data from the U.S. Census Bureau and U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics to compare small business ownership between February and April of this year, with the onset of the pandemic falling squarely in the middle of that timeframe. In doing so, Robert Fairlie, economics professor at U.C. Santa Cruz and the paper's author, reveals how the virus' effects have damaged small businesses in different communities.

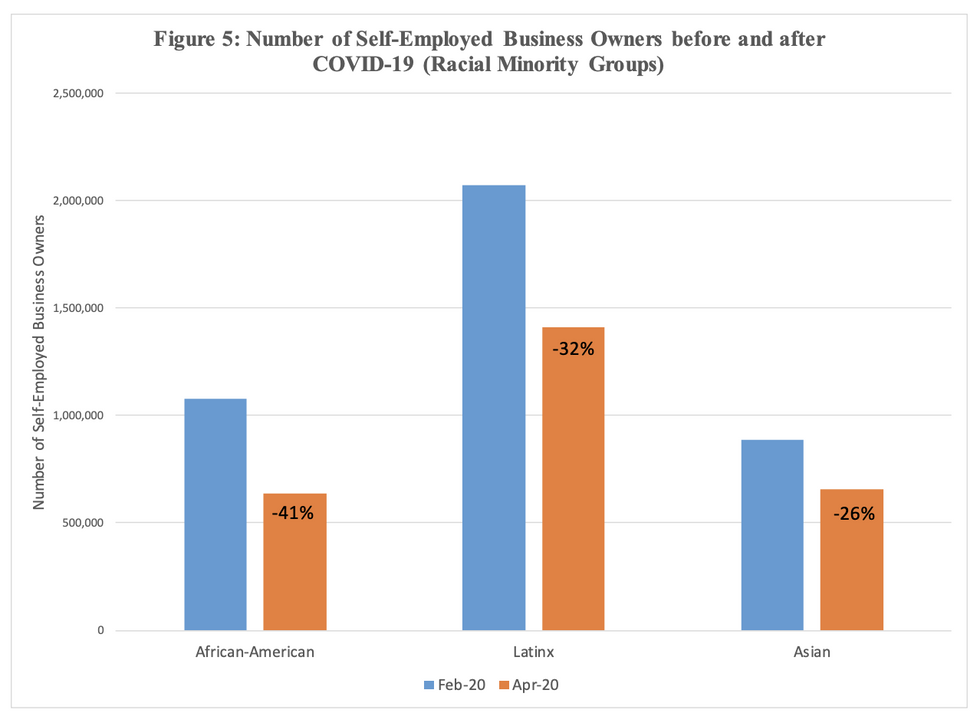

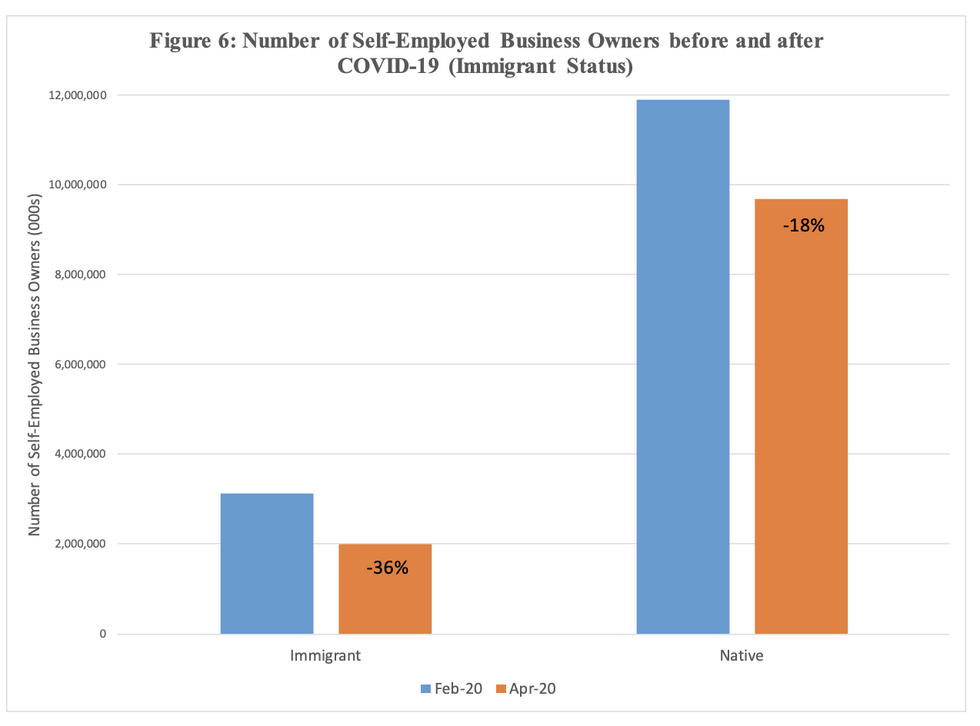

In the time period studied, the number of people who said the majority of their working week was devoted to their own business fell by 22%. Among black business owners, however, the decline was 41%. That number was 36% among immigrants; 32% among Latinx; and 26% among women.

The analysis does not break the data down by geography, but local experts see a direct connection to what's happened in the L.A. region.

Downtown L.A.-based Camino Financial, a financial services provider, recently published its own study on the current health of Latinx-owned businesses. It examined loan repayment data through May of this year, and found that Latinx businesses in California have had a 40% higher incidence of nonpayment compared to peer companies in Texas and Florida – two of the three other states besides California with the highest proportion of Latinx-owned businesses. The only other state seeing similar nonpayment rates is New York.

"There is a very strong correlation between the impact of COVID on businesses and the overall impact on the area itself," Camino Chief Executive Officer Sean Salas says. What's happened throughout the country is likely to be happening in L.A., he says. Perhaps more intensely, given that 40% of California's population is Latinx, and over 30% of the state's Latinx businesses are in Southern California.

L.A.'s black small business community was hit extremely hard, says Dr. Rhonda Thornton-Crawford, director of the USC Small Business Diversity Office. "Black business has been disproportionately distressed for far longer than the COVID-19 pandemic...We are again face-to-face with the reality of lack, loss, and limited opportunities."

Explaining the Inequity

"I've had perfect credit, I have a six-figure income, I have a degree from a great school. But institutions of all types would still see my name and discriminate," says Lilly Rocha, formally Liliana Patricia Rocha Castellar, Chief Executive Officer of the Los Angeles Latino Chamber of Commerce.

She's seen the pandemic hit her community hard.

"A lot of our smaller businesses...they're gone. They're done."

Latinx business owners have struggled to obtain emergency relief funds and leniency from landlords, among other hardships, Rocha says.

She and Salas both note that the initial implementation of the government-relief Paycheck Protection Program did a poor job of helping the businesses most in need. Some of the damage, however, has been mitigated since the program was expanded, they say.

But in explaining why minority-owned businesses have had less access to relief, Salas points to several factors that make these businesses vulnerable even in normal times.

First, Salas says that such businesses "over-index in operating informally structured companies as it relates to legal formation, cash flow management and other administrative-related tasks." This makes it harder for them to get financing at a level that aligns with their actual business needs, rather than based on what official records show. Undocumented-owned businesses are also more likely to be informal, cash-based companies due to owners' limited formal education and fear of deportation. (For what it's worth, Salas highlights his firm's estimate that, nationwide, approximately 800,000 undocumented-owned businesses generate around $100 billion in sales, "and get zero benefits in exchange.")

Minority and immigrant-owned businesses also tend to make less money and have been operating for less time on average, both of which, Salas says, exacerbate their vulnerability.

Jamarah Hayner, vice chair of the Greater L.A. African American Chamber of Commerce, adds that in the black community, "Historic problems like access to capital have been exacerbated... Most of our businesses are smaller and often family-owned, and we don't always have access to in-house or retained accountants and financial staffs, which make loan applications difficult to tackle. Further, we participate heavily in the restaurant, fitness and beauty industries, which were decimated during the shutdown. Lastly, black-owned businesses have found great success in the past decades in the manufacturing supply chain, so we've struggled as factories have shuttered."

What Comes Next?

"The next important question is whether the shutdowns of small businesses are temporary or longer term," Fairlie writes.

Salas sees the situation unfolding in three stages – relief, recovery, and reinvention – and notes that we're just entering the second stage.

"I think there's a silver lining in the reinvention to come," Salas says, pointing to four potential changes that could lay the groundwork for a more equitable future.

One is an accelerated adoption of financial technologies among Community Development Financial Institutions (CDFIs), which are meant to provide financial resources to distressed communities. In tandem, Salas says, the Community Reinvestment Act, a federal law meant to encourage lending to low-income neighborhoods, should be modernized. Its allocation of funding, for example, shouldn't be tied to banks' physical branch locations, which are increasingly closing down as the financial system digitizes.

Salas also points to the need for a realignment of incentives to drive investment from both banks and private investors.

"If we leave these businesses behind," he concludes, "over time it will come back and hurt us."

"Business leaders, businesses and communities must sit down and talk about a cohesive, concrete collective mapping of what is needed," Thornton adds. "The time is now."

- Covitech Launches to Get Small Businesses Back Online - dot.LA ›

- Minority-Owned Businesses Were Hit Hard by COVID-19 - dot.LA ›

- How To Lay Off Staff With Compassion - dot.LA ›

- Half of Latinx-Owned Small Businesses Closed During the Pandemic, Survey Finds - dot.LA ›

Sam primarily covers entertainment and media for dot.LA. Previously he was Marjorie Deane Fellow at The Economist, where he wrote for the business and finance sections of the print edition. He has also worked at the XPRIZE Foundation, U.S. Government Accountability Office, KCRW, and MLB Advanced Media (now Disney Streaming Services). He holds an MBA from UCLA Anderson, an MPP from UCLA Luskin and a BA in History from University of Michigan. Email him at samblake@dot.LA and find him on Twitter @hisamblake

Image Source: Revel

Image Source: Revel