Column: COVID Showed Me Why LA Needs a More Diverse Tech Workforce. These Students Showed Us How to Change It.

This week is national Digital Inclusion Week, but to be honest, I —like a lot of people— didn't understand the significance of this issue until COVID-19 hit. To me, the pandemic felt like a narrowly escaped disaster that I was only spared from because of my computer.

Luckily, by the onset of the pandemic, I was making enough money to retire my mom from her job as a janitor, a job which suddenly had a new risk attached to it. I was also among the fewer than 17% of all Latinos who could work remotely and protect my household in ways that were simply out of reach for most members of my community.

I felt an unshakeable sense of survivor's guilt to see the choices Latinos had to make — either physically go into work and risk it all or stay home and run out of money, fast. This ultimatum may seem dramatic but it's important to note that Latinos are significantly less likely to benefit from the social safety net (unemployment, health insurance, economic relief programs) afforded to other communities because of either the individual's or a family member's immigration status.

Roadblocks to Upward Mobility

At the time, I was working as a senior program manager at the Latino Donor Collaborative, where I had the opportunity to mentor many remarkable Latino college students. Most of our interns were attending top-tier universities on full-ride scholarships and were "seemingly normal" college students before the pandemic hit. Yet, COVID-19 reminded my first-generation college students that they were not the same as their middle- and upper-class peers.

For some, this meant moving back into crowded homes and struggling to find quiet places to study. For most, it meant that their parents would almost inevitably contract COVID-19 due to exposure via low-income essential jobs as janitors, construction workers and food distribution workers and then spread the illness to their families. On top of familial health concerns, many of my students were stepping up to make sure that their younger siblings didn't fall behind in school because their parents didn't have the technical literacy to provide support. So, it's no surprise that a national 2020 Public Viewpoint survey found that half of all Latino students canceled or changed their higher education plans, compared to 26% of their white counterparts.

If I had been born a few years later, as my interns, I wouldn't have been able to protect my family from coronavirus. It was hard to watch COVID-19 spread so predictably, based on the parents' occupations, and it reminded me of the impotence I felt as a teen, watching my stepdad be deported and losing our house during the 2008 financial crisis.

If I had been born 20 years later, I would have been one of the kids who didn't have the means or guidance to participate in virtual learning. Would I still have "made it" if I faced the exponential obstacles of COVID-era students? Probably not; it was already a by-the-skin-of-my-teeth journey as the first person in my family to attend school. How many kids won't "make it" because of the COVID-induced hurdles they are facing today?

LA Faltered

Despite being home to the fifth-largest tech market in North America, Los Angeles could not move fast enough to address the digital divide when the pandemic hit. It disproportionately affected (and continues to affect) our Latino and Black students, who are almost three out of four K-12 students in Los Angeles County. An LAUSD study found that only 50% of Hispanic and Black middle school students participated in at least seven weeks of online learning during school facilities closures — at least 30 percentage points behind their white and Asian counterparts.

The fact that distance learning was unattainable for students in 2020, in the third-richest city in the world, is inexcusable. The irony is that there is probably a significant overlap between L.A. essential workers, who risked or gave their lives to keep our basic needs met, and those whose children fell through the cracks during the remote learning overhaul.

My Pivot to Data

One reason for this unacceptable situation is that the resource allocators who had the power to address the distance-learning gap were not from our most-affected communities. That's why we also need to address another part of the digital inclusion equation: tech training for a more representative tech workforce.

After witnessing the amplified disparity in my community and recognizing the life-or-death importance of financial security, I was motivated to pivot into data and technology. In August 2021, I graduated with honors from the Data Science for All Fellowship by Correlation One. The company's mission is to provide free data analytics training to 10,000 people in the next three years and provide new pathways to economic opportunity through access to in-demand technical careers.

As part of this life-changing opportunity, we completed capstone projects using our newly gained coding and analytics skills. Over 100 teams delivered creative and impactful projects, but only the four top teams presented at graduation. To put the caliber of talent into perspective, only 1,000 of over 26,000 applicants were accepted into the program. Of those 1,000 fellows, only the work of about 24 students was presented in Grand Finale which was judged by top technology leaders.

What's Possible: The Internet Expansion Program

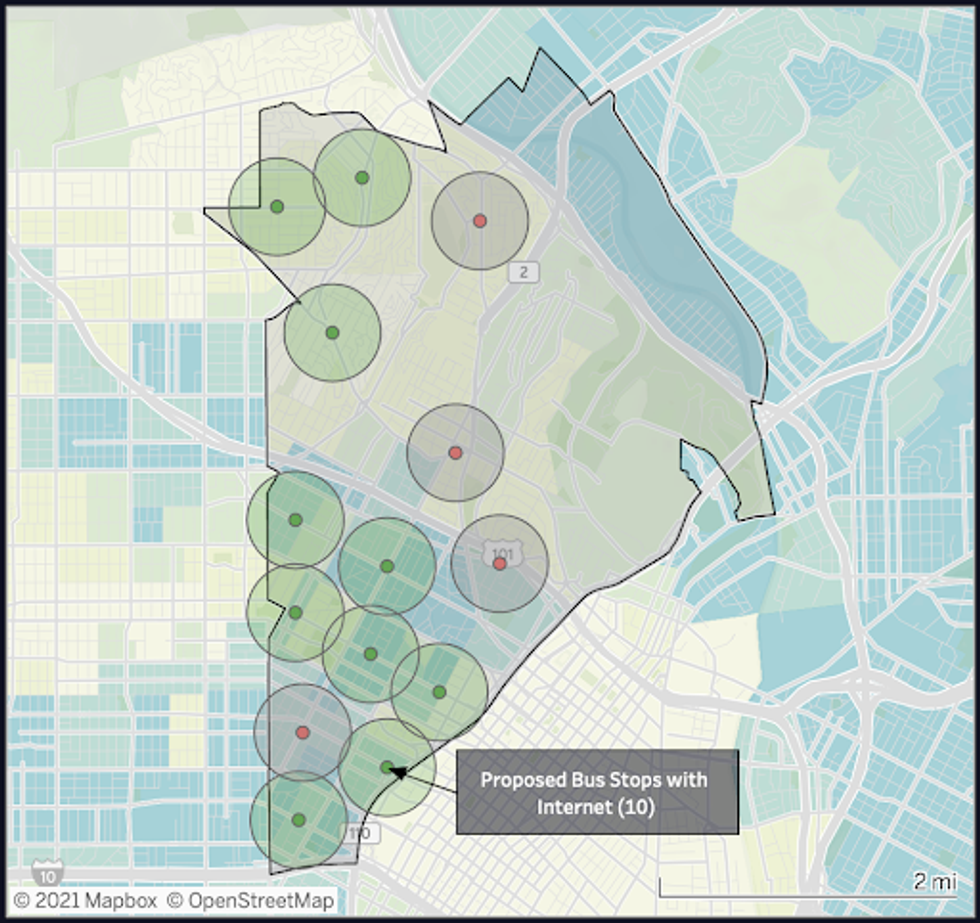

I was awestruck by a group of all Latino and Black students who applied sophisticated data science techniques to produce a cost-effective and actionable solution to L.A.'s internet gap. Team 104's project L.A. County: Internet Expansion Program identified which L.A. communities are struggling the most with internet connectivity and proposed that the local government leverage existing digitally-enabled infrastructure at bus stops (since commonly used indoor spaces like libraries and cafes were off-limits during quarantine) to provide internet access points to the people who would benefit most.

Team 104's solution targeted the East Central, Silver Lake, Echo Park and West Lakes regions because those neighborhoods have the highest rates of internet disparity by income bracket. They proposed that Wi-Fi be installed at 10 strategically selected bus stops (shown below) to increase internet accessibility by 26% in low-income, non-high school graduate households in L.A. County.

Team 104's elegantly simple solution ended up taking home second place in the DS4A Grand Finale and a $2,000 award that they donated to EveryoneOn, a nonprofit that works to democratize internet access.

Marlene Plasencia, of Team 104, poignantly reflects:

"If you look at the headlines regarding Wi-Fi and education, people are looking to the schools to solve the problem of lack of internet access for children. I think we've proven that when we have access to knowledge and tools like data science, we can take these issues into our own hands and present solutions to important social issues affecting our communities."

Mind you, they upskilled and developed this proposal in only 13 weeks. This is just an example of the innovation we're missing out on with anemic levels of diversity in the tech sector. In fact, CBRE's Scoring Tech Talent Report found that the L.A. tech workforce is currently the second-least diverse in the nation, although the city is one of the most diverse places in the country. To learn more about Team 104 and their project, click here.

Diverse Tech Training is a Competitive Advantage, Not Just a Social Responsibility

DEI arguments aside, a homogenous workforce produces less innovation. In a market that is driven by novelty and product-market fit, our tech industry's demographic makeup suggests that teams will struggle to pioneer new technology and, more importantly, even understand the needs of the increasingly diverse mainstream consumer. The gap between those building the digital landscape and engaging with it represents an opportunity loss for L.A. tech companies to understand their end-users more intimately and create better products and experiences.

Many industry-leading companies, who recognize the competitive advantage that a diverse tech workforce represents, partner with Correlation One to create fellowships so that Black, Latinx, LGBTQ+, female, and veteran talent can participate in world-class data and analytics training. These companies benefit by getting first dibs at recruiting directly from the rigorous and business-case-focused program.

Take steps today to ensure the long-term prosperity of L.A.'s tech community by connecting to organizations like Correlation One to learn how you can maximize the human capital potential of our local talent and workforce pipeline.

If you're interested in joining the Data Science for All mission to recruit "Data Science for All" fellows or to become a mentor, you can get in touch with the Correlation One team here.

This column was published in conjunction with L.A. Tech 4 Good.

This story has been updated.

- reWerk's Plan to Bridge the Digital Divide with Unused Tech - dot.LA ›

- 2022 Will Be the Year Tech Equity Moves Beyond Gesture - dot.LA ›

- Bessemer’s Elliott Robinson on Diversity in Venture Capital - dot.LA ›

- Bessemer’s Elliott Robinson on Diversity in Venture Capital - dot.LA ›

- Nex Cubed Announces the Inaugural Cohort for Its HBCU Fund - dot.LA ›

Image Source: Skyryse

Image Source: Skyryse

Image Source: Northwood Space

Image Source: Northwood Space