With the pandemic effectively vaporizing the in-person concerts business, hamstrung artists and venues seeking alternative ways to engage fans have turned to livestreaming.

Although a livestreamed show cannot completely replicate an in-person concert, the medium also presents artists an untapped creative outlet – and a new challenge: to convince their fans that ticketed shows are worth the price of admission.

"These platforms have no filter. You're not hiding behind a stage full of pyrotechnics and a carefully crafted public messaging or marketing veneer; it's just you," Tim Westergren, founder of Bay Area-based streaming platform

Sessions Live and former co-founder of Pandora, told dot.LA.

It's a high-stakes challenge, as many artists have grown to

rely on live performances for the majority of their income.

And as the pandemic runs its indefinite course, many companies are jockeying to provide artists, their teams and a music industry at large striving to stay afloat with the next generation of livestreaming infrastructure.

What has emerged is a vast, ongoing experiment to find the best way to engage fans and convince them to pay.

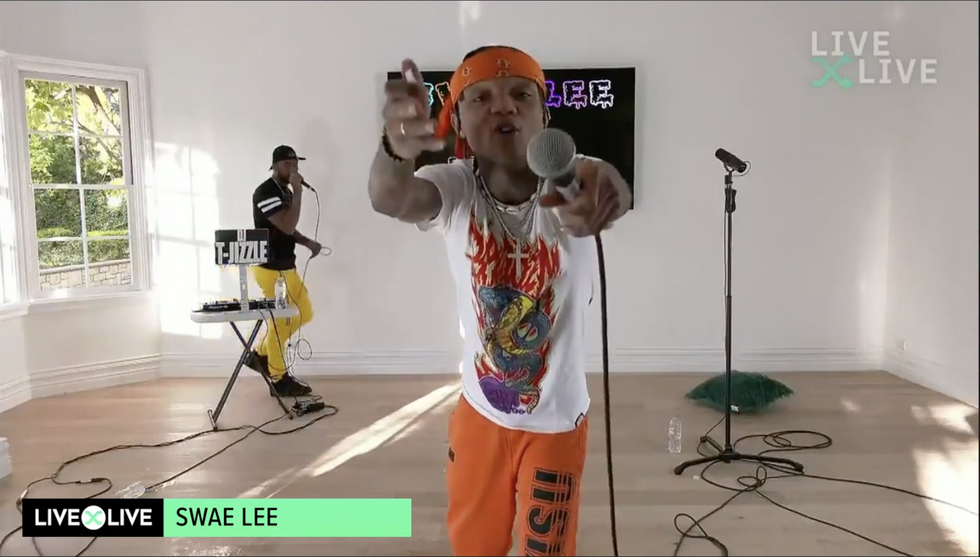

Rapper, singer and songwriter Swae Lee performs on LiveXLive.Courtesy of LiveXLive

Rapper, singer and songwriter Swae Lee performs on LiveXLive.Courtesy of LiveXLive

Born of Necessity

Livestreaming didn't receive serious attention or investment before the pandemic, not least because

the in-person concert business was booming. It wasn't until Q3 of this year that concert trade magazine Pollstar even began tracking livestreaming data.

But COVID-19 dealt the concerts business a serious sucker punch. Pollstar

forecast in April that artists, concert venues and labels were set to lose nearly $9 billion in revenue if live concerts didn't resume in 2020.

By August, Beverly Hills-based concert promoter Live Nation had

reported a 95% decline in year-over-year concert revenues.

Following a frantic period of shutdowns, reopenings and weighing options, the music industry has realized that live concerts won't be back anytime soon. It is now scrambling to figure out how to make livestreaming work.

"There was some shellshock early on," said Prajit Gopal, founder of L.A.- and NYC-based

LoopedLive, a streaming platform specialized in combining its 'digital venue' with a patented form of one-on-one digital meet-and-greets. "Over the last month or so, everybody is diving into it."

LiveXLive, for instance, a sprawling NASDAQ-listed music company based in West Hollywood, has

amped up its livestreaming shows by 289% over the last six months compared to the same period in 2019.

Greg Patterson, who'd previously been head of music at Eventbrite, told dot.LA that he saw L.A.-based

Veeps is "one of two or three companies that changed really quickly" in response to the pandemic, spinning up its first livestreamed show in March. Patterson joined Veeps in May to help the company develop its livestreaming business to complement its pre-existing suite of tools for 'long-tail artists,' such as direct-to-fan ticketing.

"Since then, there's been what feels like another company every 30 seconds," Patterson said, noting that the field remains very fluid. "It feels like the early 2000s startup period, where there were no rules."

"It's absolutely the wild West," said music industry veteran Stephen Prendergast. "To make it work we need people coming up with ideas and tech to make it more compelling; it can't be a flat, one-screen dimension."

In other words, artists sitting in their bedrooms and broadcasting on Instagram and Facebook won't cut it.

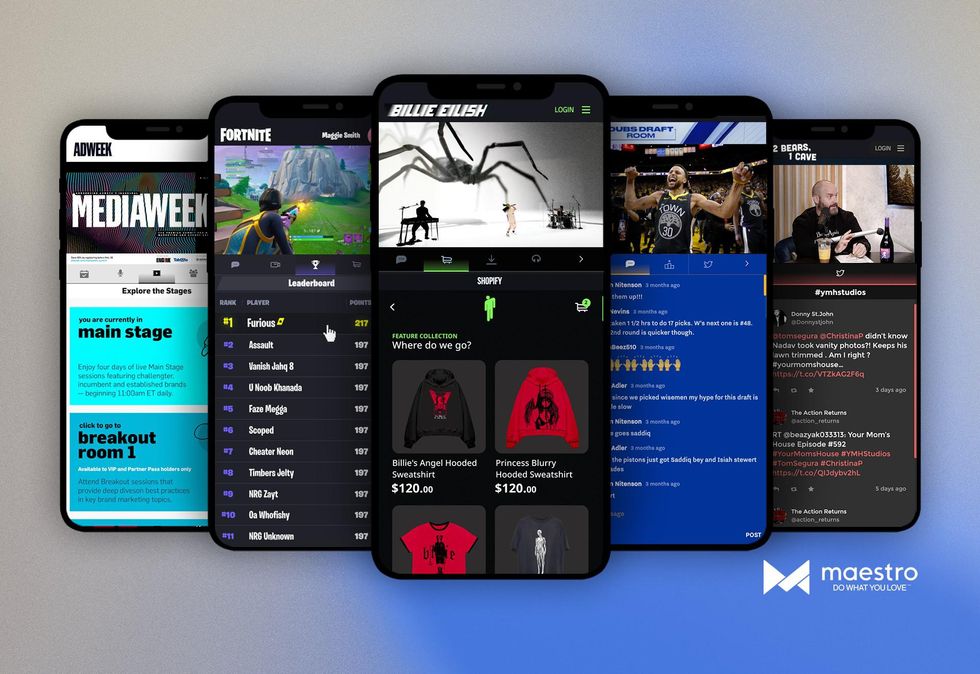

Image courtesy of Veeps

Image courtesy of Veeps

More Than a Concert

New solutions have sprung up to do what concerts do best: put fans in the same space as the bands they love. But because a digital show has its limitations, there are also ongoing efforts to provide fans with online experiences that they wouldn't find at a traditional concert.

"I always say, 'do things in digital that you can't do in the real world'," LiveXLive President Dermot McCormack told dot.LA.

Many streaming services have started to provide coaching services to help artists exploit the unique opportunities a digital platform affords, and increasingly so as data comes in showing what works and what doesn't.

"If you do the same thing over and over again, people won't want to tune in," Gopal, LoopedLive's CEO, told dot.LA. When his company hosted a livestreamed show for the cast of "Hamilton," the performers used LoopedLive's private meet-and-greet feature for more than 'Hi, how are you.' Lin Manuel-Miranda, for instance, regaled fans with freestyle raps about a topic of their choice, and some cast members gave quick dance lessons.

During Grammy-winner Brandi Carlile's Veeps stream in early October, she and her band paused the show for a 30-minute fan Q&A that spanned topics from whether the band ever gets on each other's nerves to how life has been during the quarantine and the status of Carlile's forthcoming book. The band then obliged a fan's request to sing happy birthday to her daughter.

McCormack pointed to a 20-minute Q&A one artist hosted in the middle of a LiveXLive-hosted performance. "The fans lapped it up," he said. "We had to switch off the comments, they were moving so quickly."

Fans also seem to like when artists lean in to the sort of unmediated intimacy that accompanies livestreaming. "Artists'll play a song and go 'fuck, let me start again' – fans love that; in comes a basket of tips when that happens. It's about relatability and connection," said Westergren.

For K-Pop artist James Lee, "there's definitely a rush" that comes with livestreaming. Lee, who has performed on Sessions, told dot.LA that, "I have not been on stage in over a year. [Streaming] feels very intimate. There is more of a burden because nobody is in the room with you and everything depends on me."

Linkin Park's Mike Shinoda took that intimacy to another level with his three-volume album, "Dropped Frames." Shinoda's fans on Twitch suggested themes and lyrics that he transposed into songs, some of which even included fan-submitted vocals.

More such experimentation is likely to come.

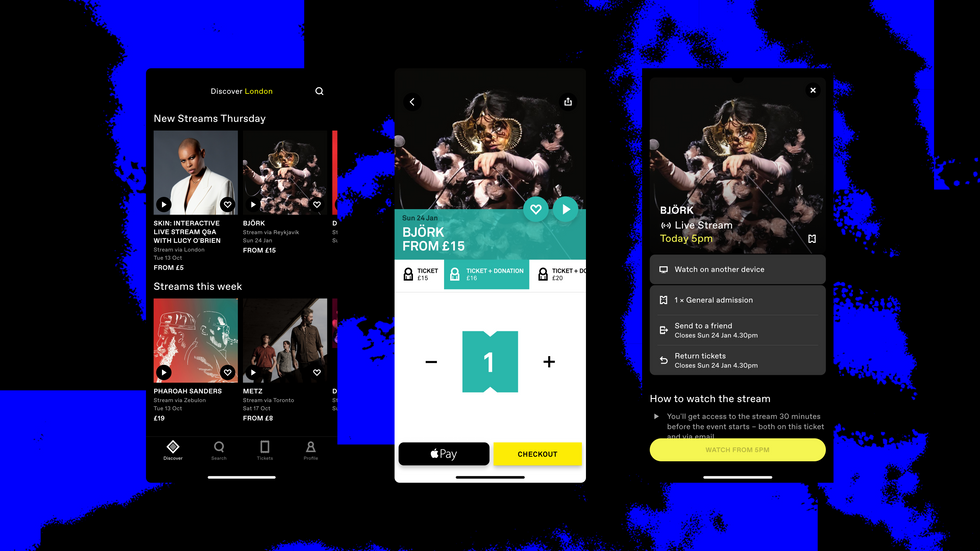

DICE general manager of North American operations Shanna Jade Vélez told dot.LA she is "expecting to see a lot more innovation when it comes to interactivity." The company began operating before the pandemic as a live-ticketing discovery platform, available in seven countries. It has since streamed over 4,000 shows and sold tickets in 145 countries.

K-Pop megastars MonstaX perform on LiveXLive's platform. Courtesy of LiveXLive

K-Pop megastars MonstaX perform on LiveXLive's platform. Courtesy of LiveXLive

Putting on a Show

Live chat has become a regular feature of livestreamed concerts, enabling concertgoers to message one another.

Mandolin offers private chat rooms for groups of fans to congregate; the Indianapolis-based company launched in response to the pandemic and recently raised $5 million in seed funding.

Other startups are working to translate fan input – like clicking 'like' buttons – into a crowd roar that gets transmitted to musicians on the other side of the screen.

FanTracks is one such service. It's also providing concertgoers a "director's chair" that gives them the option to toggle camera views. And it is one of many platforms experimenting with augmented reality to "transport" the performers to different locations.

Peter Shapiro, owner of several venues including the Brooklyn Bowl, is founder of

Fans, a concert-streaming platform that transports audience members themselves, by allowing them to beam their video-feeds onto screens at venues where livestreamed performances are held. The technique is similar to how the NBA has allowed its fans to project their video-feeds onto screens in the stands.

Taking virtual transportation a step further, L.A.-based

Wave renders musicians into digital avatars who interact with and perform for fans in otherworldly settings where the laws of physics are optional. The company raised $30 million in June and has hosted concerts by John Legend and The Weeknd. Produced in partnership with TikTok, the Weeknd's show reportedly attracted 2 million unique viewers.

Similar to Travis Scott's

virtual concert series in April – where a giant, digital rendering of the hip-hop artist performed for over 27 million viewers across five shows hosted on Epic Games' Fortnite – Wave concerts are created with gaming engines and can be accessed by viewers via PC, gaming consoles or VR headsets. Unlike the Scott concert, however, which was pre-recorded and then rendered into Fortnite's virtual venue, Wave's avatars perform in real-time.

The TikTok live event featuring the Weeknd and Wave's technology brought aspects of gaming to live concerts.

Whether artists perform as an avatar or their unvarnished selves, Veeps has found that fans seem to prefer some degree of predictability on what they will see in a livestream. Similarly, Vélez said DICE is finding that fans want "a reason" to purchase a ticket. Some artists are turning to filming shows at big, deserted, "hauntingly beautiful" sets like churches and palaces, she said.

Patterson added that shorter shows, around 45 minutes, also seem to perform well, and noted that the user interface must be premium.

"It has to be on the level of watching a movie on Netflix or Disney Plus," the Veeps executive said. "If you mess it up, with so many other options, no one's going to want to come back."

Anyone who's shelled out $100 for a concert wouldn't necessarily point to the auxiliary pieces surrounding a show – the lighting, the refreshments, the bathrooms – as key to the experience. It's the performance that matters. But in the digital world, the areas ancillary to the performance are opportunities for virtual venues to distinguish themselves. So says L.A.-based streaming platform Moment House.

"If you make fans feel that they're part of this very elegant, premium and special place of a moment, we can make this a cultural phenomenon,"

Moment House co-founder Arjun Mehta told dot.LA. "We saw that thesis in our beta stage play out really nicely."

Moment House debuts this month, with a focus on user experience. Mehta developed the idea as a student in the inaugural class of USC's Jimmy Iovine and Andre Young Academy, a program that focuses on the intersection of design, engineering, management and communication. The company has raised a $1.5 million seed round led by Forerunner Ventures with investors including Scooter Braun, Troy Carter and actor Jared Leto.

DICE began operating before the pandemic as a global live-ticketing discovery platform. It has since streamed over 4,000 shows and sold tickets in 145 countries.Image courtesy of DICE

DICE began operating before the pandemic as a global live-ticketing discovery platform. It has since streamed over 4,000 shows and sold tickets in 145 countries.Image courtesy of DICE

What's Next?

As this experiment continues and the culture and technology of virtual performances grows, we could be entering a new paradigm for musicians and their audiences.

"The early-90s internet is unrecognizable compared to what we have today and I think visual content and music will become unrecognizable to what we have now," Patterson of Veeps said.

One example of new technology that could open a world of possibilities is

Aloha by Elk, which launches in beta this month and will allow musicians to play together in real time from hundreds of miles away.

"Playing together over the internet is something that musicians have been dreaming about since Skype: 'We can talk, but why can't we play?'" Michele Benincaso, founder of the Stockholm-based Elk Audio, the company behind Aloha, told dot.LA. The answer: latency.

The delay between someone speaking over Zoom or Skype and someone else hearing it is usually between 500 milliseconds and 1 second. The delay itself often fluctuates, a process known as "jitter." These issues make playing together on beat effectively impossible.

Solving these problems, as Aloha aims to do, would clear the way to a whole new path for livestreamed concerts.

"I could think of hundreds of examples for things that haven't been done today," said Sharooz Raoofi, a musician and tech entrepreneur who splits his time between L.A. and London. He is one of a few artists who's worked with Aloha prior to its upcoming beta launch.

"If you think about legendary festival performances, like when a guest vocalist jumps on stage and sings a track – that can't be done in digital unless it's latency free," Raoofi told dot.LA. "Even in the best of times, trying to get musicians together is tricky – more so if it's multiple bands. Doing that remotely without any latency could be a game changer."

For now, the maximum distance Aloha can manage is about 1,000 miles, enough to allow musicians in different countries to play together. As this technology develops and the distance grows, however, the possibilities may become virtually endless.

A Band-Aid or a Bridge to the Future?

Whether livestreaming becomes an enduring pillar of the music industry or fades into a fad once the pandemic dies down will depend on whether it can bring in enough money and deliver a new kind of experience.

"I was really struck that someone made $10,000 in a show with 300 people attending – and I can guarantee you there's not a room anywhere in the world that that artist could sell out," Westergren said of a performer who streamed on Sessions. "Historically there are only two ways for an artist to get paid like that. One is to spend years on a stage, grinding and touring. The other is to get plucked out of obscurity by the powers that be."

"Livestreaming can solve that, but only if you have monetization," he said.

---

Sam Blake primarily covers entertainment for dot.LA. Find him on Twitter @hisamblake and email him at samblake@dot.LA

From Your Site Articles

Related Articles Around the Web

Rapper, singer and songwriter Swae Lee performs on LiveXLive.Courtesy of LiveXLive

Rapper, singer and songwriter Swae Lee performs on LiveXLive.Courtesy of LiveXLive Image courtesy of Veeps

Image courtesy of Veeps K-Pop megastars MonstaX perform on LiveXLive's platform. Courtesy of LiveXLive

K-Pop megastars MonstaX perform on LiveXLive's platform. Courtesy of LiveXLive DICE began operating before the pandemic as a global live-ticketing discovery platform. It has since streamed over 4,000 shows and sold tickets in 145 countries.Image courtesy of DICE

DICE began operating before the pandemic as a global live-ticketing discovery platform. It has since streamed over 4,000 shows and sold tickets in 145 countries.Image courtesy of DICE