The LAPD is facing criticism from privacy groups after SweepWizard — an app it used to conduct multi-agency raids last fall — exposed the personal data of thousands of suspects and details of police operations. Earlier this month Wired reported that LAPD and the regional Internet Crimes Against Children (ICAC) Task Force used a free trial version of the app to conduct multi-agency raids on sex offenders. While the app led to the arrest of 141 suspects, it also revealed sensitive details on police operations that could have put the entire mission at risk.

“LAPD has a long history of using free trials of surveillance technologies to experiment on our communities, especially in Skid Row and other Black and brown neighborhoods,” said Tiff Guerra, a researcher with the Stop LAPD Spying Coalition.

In 2020, the Los Angeles Times reported that the LAPD ended its relationship with controversial predictive policing program PredPol. Though Los Angeles Police Chief Michel Moore claimed the decision was due to financial constraints, community activists argued that Moore’s decision only came after they pressured the department to discontinue the program.

Guerra also cited the police department’s use of social media surveillance tools like Dataminr and Skopenow, which officers use to regularly monitor the online activity of suspects as well as search for certain terms.

“Every day, LAPD generates and collects sensitive data about our locations, associations, appearance, interests, and relationships. LAPD tracks and maintains this data regardless of whether a person is suspected of any crime,” they said.

Guerra added that ODIN Intelligence — the company behind SweepWizard — sells another app that uses gait and facial recognition to track homeless communities. Known as the Homeless Management Information System, or HMIS, the app lets users create a profile for each unhoused resident that includes their photo and personal data, including prior arrests, temporary housing history and contact information for family members and parole officers. The app’s facial recognition feature allows police to identify unhoused persons by searching for a match in the larger database.

None of this is particularly new. Law enforcement agencies have regularly used third-party surveillance tech — such as location-tracking and social media monitoring apps — to spy on suspects. But digital privacy groups say that the marketplace for such police tech faces few restrictions. “There are many privacy and safety harms caused by police using third party surveillance technologies including wrongful arrests, over-policing, and data breaches like this one. The marketplace for police tech is unregulated and full of poorly designed and poorly implemented software,” said Jake Wiener, counsel at the Electronic Privacy Information Center (EPIC).

Wiener also stressed that the police shouldn’t have used a free trial version of an app on “live cases”, as the LAPD did with SweepWizard. “Unfortunately, free trials are a common sales technique in the police tech market, and often lead to individual officers using tech without the knowledge or approval of supervisors,” said Wiener.

ODIN Intelligence — the company that developed SweepWizard and other police surveillance apps — regularly held a “Sex Offender Supervision Officer Bootcamp” to train officers on how to use the SweepWizard app. Screenshots of the app posted on the bootcamp’s website indicate that the third-party app allowed police to input personal details on targets, including address, date of birth, social security number and a photo. The app also includes a section for officers, which allows the user to assign specific targets to officers by name.

Wiener said that storing sensitive information such as addresses, identifying details and social security numbers is a “substantial privacy risk” and likely isn’t necessary to make the app work.

Following the Wired story’s publication, TechCrunch reported that an unidentified hacker on Sunday exfiltrated data from the website for ODIN Intelligence. The hackers defaced the website, leaving behind a message that claimed that “all data and backups” on the company’s servers had been shredded. The company’s website was quickly taken offline, and remains so as of Wednesday afternoon.

The LAPD is currently investigating what caused the SweepWizard breach, and has suspended use of the app. dot.LA has reached out to the LAPD for an update on its investigation, but has yet to hear back.

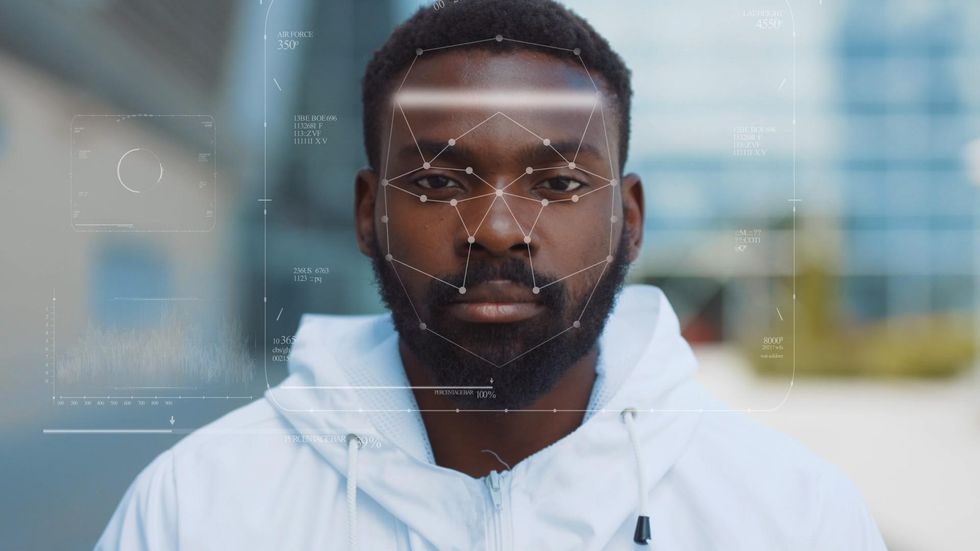

The technology employed by the LAPD ignores pigmentation, according to an officer who oversees it, instead digitally mapping the face by looking at things like the distance between the eyes, or the distance from the nose to mouth.Shutterstock

The technology employed by the LAPD ignores pigmentation, according to an officer who oversees it, instead digitally mapping the face by looking at things like the distance between the eyes, or the distance from the nose to mouth.Shutterstock