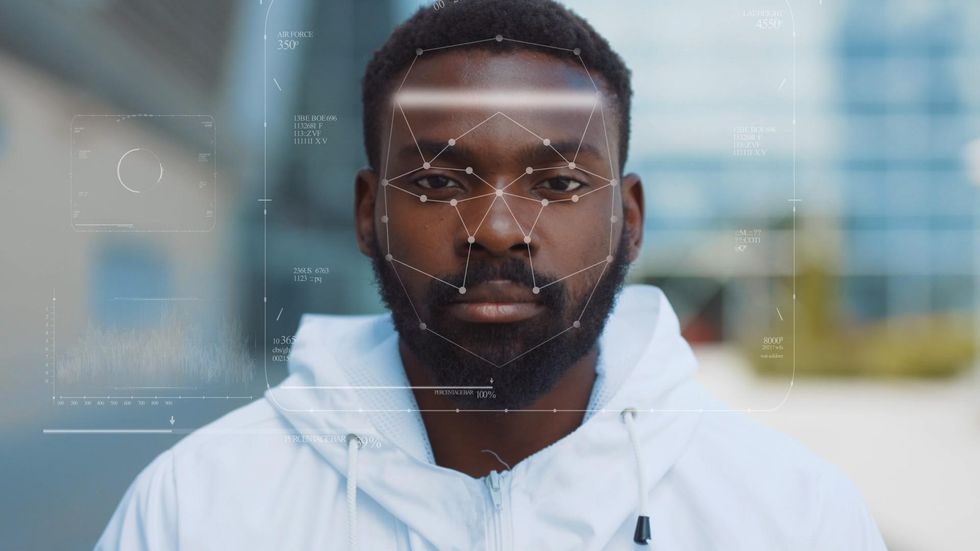

In LA, the Fight Over Facial Recognition Tech Is Just Heating Up

In Los Angeles, the cameras are everywhere. Cameras at traffic lights. Cameras on doorbells. Cameras on billions of smartphones. When your photo is snapped by these cameras, facial recognition technology can match your face to a database of millions of mug shots, potentially linking you to a crime.

Is this legal? Is this fair? Is this right?

These questions loom large over the technology, which the Los Angeles Police Department has been using since 2009. In November, an investigation by BuzzFeed News found that the LAPD had used the tech 30,000 times in the last decade, including using the controversial "Clearview AI," which trawls the internet for social media photos. Activists, furious over the investigation's findings, sought a ban on the tech. In January, the LAPD adopted what's effectively a "compromise" policy that prohibited the use of Clearview AI and other third party databases of photos, but allowed them to use Facial Recognition Technology (FRT) with their own in-house database of mugshots.

Flash forward six months. After road-testing the system, the LAPD said it's an effective tool that's being used with restraint, rapidly speeding up the time it takes to scroll through mug shots and helping to catch crooks. Activists say it should be forbidden, and that it disproportionately impacts communities of color.

"You have to look at the broader context, and where it fits in the broader 'stalker state,'" said Hamid Khan, founder of the Stop LAPD Spying Coalition. "This is not a moment in time, but a continuation of history."

The roots of the "stalker state," according to Khan, go back to the Lantern Laws of the 18th century, when Black people were required to carry lanterns after dark. Since then, we've seen a number of policies that have disproportionately targeted Black and Latinos, ranging from New York City's "stop and frisk" to the Department of Homeland Security's more recent "Suspicious Activity Reporting" program (a partnership between federal and local law enforcement), which allows anyone to report perceived sketchy behavior to the authorities. One audit found that Black people were reported in 21% of these "suspicious activities," even though they only represent 8% of Los Angeles County.

Activists worry FRT takes a pattern of discrimination and merges it with the brutal efficacy of surveillance tech.

"The danger now is that you're going to subject certain neighborhoods, certain people, and certain religious groups to this constant ever-present surveillance," said John Raphling, a senior researcher on criminal justice for Human Rights Watch. Raphling said that the Fourth Amendment, as established in 1979's Supreme Court case Brown v. Texas, means that the police can't simply waltz up to you and demand to see your ID for no reason.

"With FRT technology, that's out the window," said Raphling. "You're being identified at all times — who you are, what you're doing, who you're associating with." His concern is not just FRT itself, but the broader apparatus of sophisticated law enforcement – predictive analytics and data crunching from the photos, as now "you can't go out in public life without being under this surveillance."

The tech has been accused of racial bias, as research suggests the algorithms powering facial recognition lead to a higher chance of false matches for minorities and women. In one cheeky experiment, the ACLU used Amazon's facial recognition software ("Rekognition," which is not the software used by the LAPD) to compare the headshots of Congress with a database of mugshots, and they found that a whopping 39% of the false matches came from representatives who were people of color, even though they constitute just 20% of Congress.

Bita Amani, part of the Center for the Study of Racism, Social Justice, and Health, adds that constant surveillance likely poses an underappreciated health risk to marginalized communities, and that even if the facial recognition is flawless and accurate, it's just "strengthening and expanding the powers of the system that already targets the Black and the poor, and the people at the margins."

The police, of course, see all of this quite differently.

"This is not a sole identification tool. Ever," said Captain Christopher Zine of the LAPD. "This is basically a digital mug book." In the old days, you'd need to flip through stacks of photos and try to eyeball a match. It's slow. It's tedious. Now the system takes a photo and then queries it against the database Los Angeles County Regional Identification System database (LACRIS), which contains 7 million photos from 4 million people. (The LAPD clarified that the photos come from decades of arrests, and include non-L.A. residents.)

Lieutenant Derek Sabatini heads up the LACRIS system. He is well aware of the concerns over bias, but suggested that facial recognition technology, in a certain sense, can be employed to reduce the role of implicit bias. If humans do indeed harbor implicit biases, maybe tech can help inject objectivity?

In the traditional use of a photo, said Lt. Sabatini, "you might look at a male Hispanic and then filter that search" based on race or gender. But the FRT works differently. (The department prefers the term "PCT", for Photo Comparison Technology.) Sabatini said that the PCT employed by the LAPD ignores pigmentation, and instead digitally maps the face by looking at things like the distance between the eyes, or the distance from the nose to mouth.

Sabatini gives an example. One time the cops were trying to catch someone who was stealing packages off porches. They had a photo of a tattooed individual, and just from a casual glance, it appeared to be an Hispanic man. When they zapped the photo through the database, it was found to be an Hispanic woman, whom they arrested and charged in court. Sabatini said the facial recognition technology "actually takes away any bias in the user and just kind of goes, 'here's what's best, based on what you're providing me.'"

Some of the tension — and apprehension — seems to be a conflation between what's possible and what is actually being done. The activists fear the worst ("look at the history of the criminal justice system," said Khan) and the cops insist they are following a reasonable protocol.

"One of the big misconceptions is surveillance," said Sabanti, who explains that live feeds (such as continuous footage from an elevator camera) are not being dumped into the LAPD's records and then later mined for algorithmic dark sorcery. "You can't just have live feeds going through a system," he said. "We don't have the capability of that, and it would be against the law."

The department is also forbidden from using third-party photo databases or tools like Clearview AI. Every photo needs to be legally obtained, and to help solve a crime.

Captain Zine said that since the January protocols were enacted, the department created additional processes to ensure that only their own LACRIS database is being used, that extensive training is in place, and that only a small subset of the LAPD even has access to the tool. As for any official numbers, or quantified results and updates? This is still TBD. Zine said the LAPD is still conducting an internal review of FRT's effectiveness, and declined to provide numbers before that's finished (which he expects will be in September).

Critics like Khan, Raphling and Amani think that this middle ground is not enough, and that the potential for abuse — and the troubling history of discrimination — is itself reason enough to ban the tech. Khan points to reports that the LAPD sought photos from Ring doorbell cameras during the Black Lives Matter protests, as well as a high-profile false arrest in Detroit, although he is not aware of any specific abuses of the system, or examples of discrimination or misuse since the January protocol went into effect. The concerns seem to be more about the lurking threat of the ever-more-powerful "Stalker State" technology, as opposed to the more narrow use of the "digital mug book."

Others remain deeply skeptical. "Their argument is 'just trust us,'" said Raphling, arguing that law enforcement has a history of saying "we use it in this very minimal way," but that "it turns out they were using it vastly more." He added, more bluntly, "we would be suckers to trust them again."

Sabanti said he understands the broader concerns around a creepy, "Black Mirror"-esque surveillance state. "That stuff scares us as much as it scares the public. I don't want that," he said with a laugh. "I think we're all on the same team, and people forget that."

Lead image by Ian Hurley.

Correction: An earlier version of this post mis-spelled Hamid Khan's name.

- How Can L.A. Tech Promote More Diversity in Its Ranks? - dot.LA ›

- Unarmed CEO Tony Rice II Developed His Startup - dot.LA ›

- New Tech At LAX Aims To Speed Check-Ins, Keep Flyers Safe - dot.LA ›

- The LAPD Spends Millions On Spy Tech — Here's Why - dot.LA ›

- TikTok Tests auto scroll Feature Amid Growing Concerns Over App's Impact on Young Users - dot.LA ›

Image Source: Skyryse

Image Source: Skyryse