When I first spoke to Jamil Mehdaoui, an architect and former Oculus employee, he’d just returned to Paris from a weeklong pilgrimage into the future of movie making. Mehdaoui describes his work as “a collaborative process” between himself and the artificial intelligence that brings dream worlds to life with just a few key words. On Zoom, he occasionally appeared frustrated. Eager. Unsure. Hopeful.

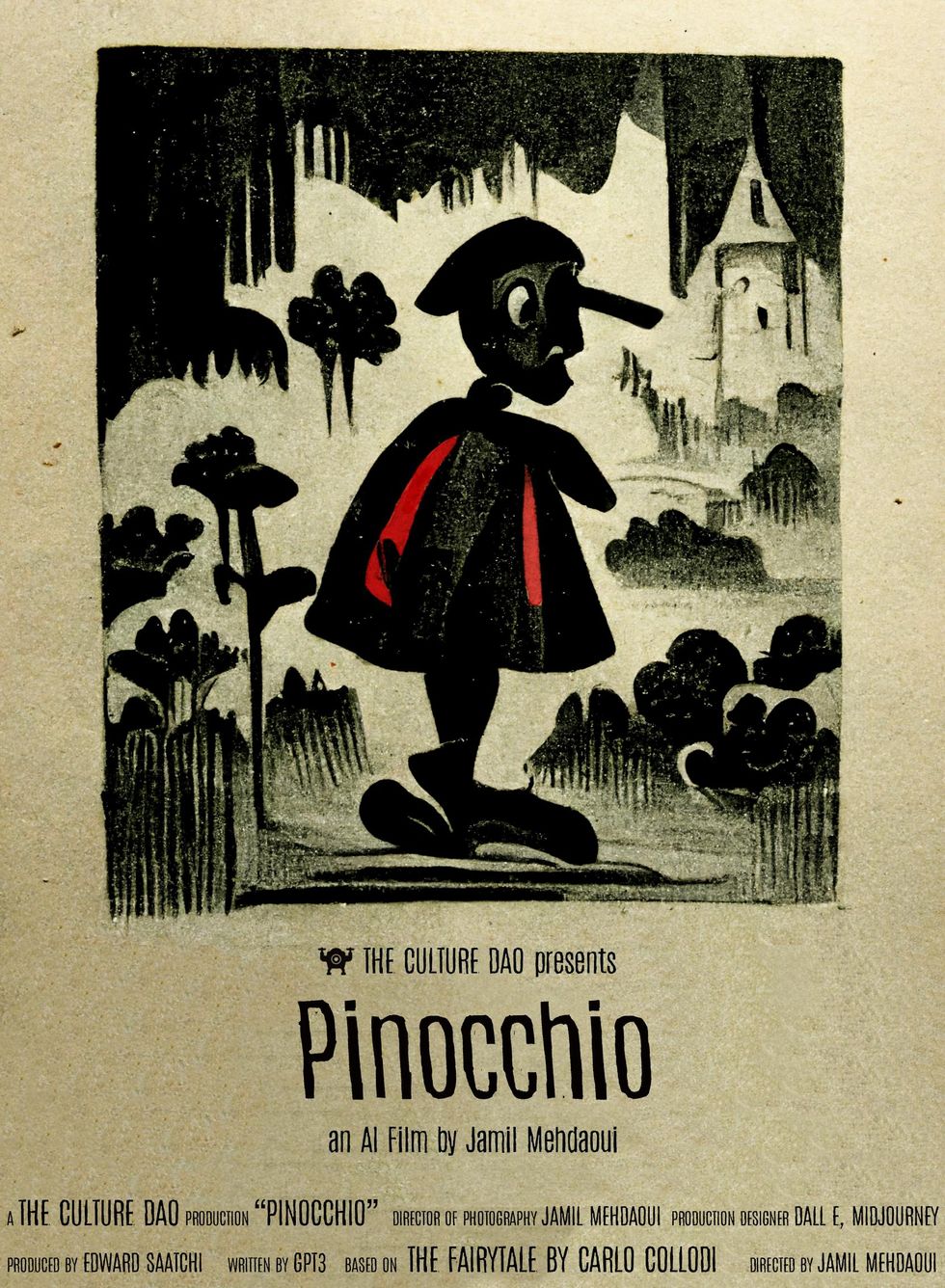

Like millions across the world, Mehdaoui is experimenting with Midjourney, a text to image program that generates images from a repository of data that spans the entire history of art and human existence as it’s cached online. Unlike millions, Mehdaoui is attempting to use this tool to make the first ever AI-generated feature film. And appropriately, he’s chosen to remake Pinocchio — the story of the first ever artificial boy.

Like the more well-known text to image AI tool — DALL-E — Midjourney’s output depends on art that’s already been made and photos already taken. But since Midjourney can’t read Mehdaoui’s mind (yet), it takes time to find the right levers to pull in order to get the AI to do what he wants it to.

For example, Mehdaoui was initially focused on prompting the AI to generate images of a boy fashioned from gnarled, raw wood. The troubles were myriad. First, Mehdaoui says, “The moment you ask the AI for Pinocchio, you lose control. It puts you in Disney’s hands.” Meaning the images the AI generated were often too familiar. Too recognizable. The other issue was getting the AI to see or rather interpret beyond such a generic descriptor as “boy that looks like a log.” So, for days, Mehdaoui tinkered with his prompts until his fragmented vision, the one cradled only in his mind, came to life, authored by artificial intelligence.

As the director of the movie, Mehdaoui has full creative control over his AI-generated Pinocchio. But there’s no studio backing his project. Instead, he’s one of 750 artists, architects, AI engineers, storytellers, animators, game designers, interoperability explorers and business folks who have joined together to dethrone Hollywood.

The Culture DAO is a “metaverse guild” assembled by Edward Saatchi, the chief executive officer (CEO) of Fable, an artificial intelligence-powered virtual being company, and the founder of Oculus Story Studio. Members of the DAO include current and former storytellers from Pixar, Lucasilm and Oculus, many of whom are currently working on an amuse-bouche of fairy tales, horror flicks, animations and live-action shorts.

Saatchi assembled the guild out of a concern that the most zealous artists interested in AI might waste too much time playing around with new features. “You could go two years, making very small demos and creating nothing substantial that’s going to last for 100 years,” he says. And since Saatchi believes AI-generated media is the beginning of a new art form, it was important, he says, to “encourage artists to find personal stories they want to tell that are empowered by AI.”

One of those artists is Scott Lighthiser — a VFX artist who studied production in college and has been experimenting with filmmaking techniques ever since. “But when Stable Diffusion [another AI powered text to image model] was released I could generate super realistic cinematic images,” he says.

Unlike Mehdaoui, who’s using AI text to image programs to animate a feature film, Lighthiser is working iteratively on developing short live-action clips. He’s posted a few of these videos on Twitter. The response has largely been one of shock. It seems few people expected the AI to be this good, this quickly. The first video shows how Stable Diffusion can add a layer that further immerses Lighthiser’s own face into a purple-skinned character. The second flaunts Stable Diffusion’s ability to quickly disguise Lighthiser’s body, rendering variations of a hissing monster. That Lighthiser was able to create these short clips on his own, a week apart, is part and parcel of how the Culture DAO plans to take on Hollywood.

“Being able to make animated movies not in seven years but in several weeks or being able to make live-action, effect heavy, content not in several years with hundreds of millions of dollars but in several weeks and with thousands of dollars, I think is going to massively democratize what’s possible,” says Edward Saatchi.Their recent progress aside, Saatchi’s proposition to decentralize Hollywood by democratizing access to the resources of a studio is still in its infancy. The Culture DAO’s current slate of content is mainly focused on horror and animation. Horror because audience expectations around having stars and a big budget are lower and the AI program offers some really creepy effects. And animation because the output is more technically suited to AI text-to-image programs.

But even in this time of great daydreams and ambition, not everything is going according to the plan. Since our initial conversation, Mehdaoui has already had to parcel his concept for the first feature length AI film into seven serialized episodes. And though Lighthiser’s short clips suggest a light at the end of the tunnel, they’re far from a finished product. “If we're talking about shooting an empty room and processing it to look like a 19th century Victorian mansion, I don't think we're there yet but probably pretty close,” says Lighthiser. “I think using AI in conjunction with LED Volume technology has the potential to be extremely powerful. But eventually you'd want to be able to take your phone out, point your camera at a barn and say ‘turn the barn into a spaceship’ and it renders it in real time.”

Naturally, there will always be detractors who argue any AI-generated art is merely “visual gibberish.” In fairness, much of what appears on Twitter does appear that way. Others critics have genuine ethics and copyright concerns. Like—what happens if everyone’s AI art steals from the same artist?

But Saatchi says these concerns are the growing pains at the frontier of a new artform. This moment, he says, is like the early days of Pixar. Back when the technology company failed to sell computer hardware and pivoted toward creating computer-animated shorts.

If even half of what the Culture DAO is promising becomes reality, Hollywood’s place as the entertainment capital of the world is imperiled. Most of the members of the DAO are spread all across the world. To some degree, this reckoning is already underway: In August Belfast-based composer and computer artist Glenn Marshall won the Jury Award at the Cannes Short Film Festival for his AI film “The Crow.”

More recently, Fabian Seltzer, co-founder of the Culture DAO along with Saatchi, was in the news for his AI-generated, choose-your-own-adventure movie fashioned after 70s-era sci-fi films. Both projects were essentially created out of an individual's home office.

“What I saw at Pixar—what I see in VFX— is that brilliant people who might not be entrepreneurial enough to start up their own studio, are being crushed in their creativity because it’s such a factory system,” says Saatchi. “It’s shifted to being about cost management and the creativity has gone down and these projects require so many people and so many resources.”

With AI, however, the number of people it takes and the amount of money required to make a Pixar-quality film doesn’t just have the potential to be cut in half, it might well be a fraction of the $200 million budgeted to produce many of these movies.

Saatchi’s message to the folks in Hollywood? “It’s time to get out and develop your own project.”

- Creatives Fear AI Generated Art Is Coming For Their Jobs - dot.LA ›

- Art Created By Artificial Intelligence Can't Be Copyrighted - dot.LA ›

- Disney's New AI Can Auto-De-Age Actors - dot.LA ›

- The Lensa Art Trend Sparks Controversy About Sexism In AI - dot.LA ›

- Is 2023 the Year of a Hollywood Writers' Strike? - dot.LA ›

- Anime Artists Are Mad Netflix Japan Used 'Image Generation' - dot.LA ›

- Darren Aronofsky on Why the Human Effort is Irreplaceable - dot.LA ›

- Storia is Betting Big on Hollywood’s Desire for AI Movies - dot.LA ›

- Is AI Art Real Art or Just a Gimmick to go Viral? - dot.LA ›