The global market for small satellites is booming. A report from Trends Market Research last April estimated that the industry will reach a value of $15.3 billion by 2026, propelled mainly by the deluge of satellite companies big and small that are eager to capitalize on low launch costs.

But one common problem most companies face is lengthy wait times to receive a satellite bus— the main body of a satellite that holds all its key functions, scientific instruments and payload.

Enter Apex Space, a Culver City-based startup that is building a factory to make satellite buses at what it claims can be a fraction of the time it takes these contractors to finish one.

CEO Ian Cinnamon, an alumnus of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology and Stanford, believes his new venture can outsmart legacy players in the satellite manufacturing business. He is working to scale Apex alongside CTO Max Benassi, a former senior engineer at SpaceX.

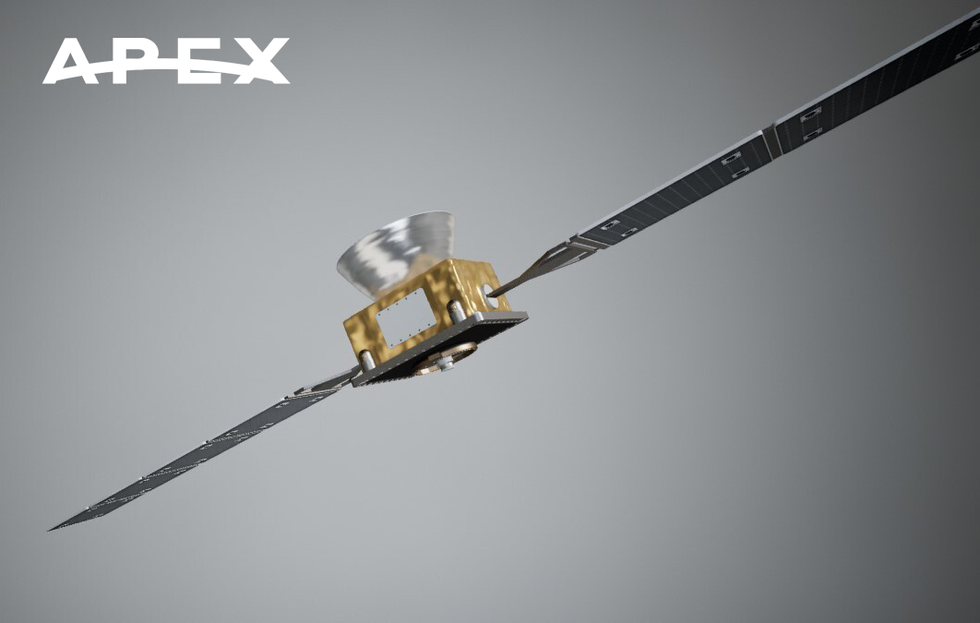

On Monday the company raised a $7.5 million seed round led by Andreessen Horowitz to fund development of its first product, the Aries satellite bus—a spacecraft that’s capable of carrying payloads of up to 200 pounds into orbit. The seed round also included investment from XYZ, Lux Capital and Village Global.

The startup enters a crowded field. Established federal contractors like Lockheed Martin, Boeing and Northrop Grumman are actively deploying satellite buses for the U.S. government (including the Space Force and the Department of Defense’s Space Development Agency). Additionally, Boeing opened a new factory to build small satellites in El Segundo this March to house its subsidiary Millennium Space Systems, another competitor to Apex.

On the startup side, there’s existing bus makers trying to outpace the big players, including Denver-based York Space Systems and Terran Orbital, which has an outpost in Irvine.

But Apex’s bus is built different. Designed to be sort of plug-and-play, meaning it can carry a variety of different payload types and could work for different customers, the Aries satellite bus is designed to support a range of missions and will be mass-produced. Cinnamon said Apex aims to build its first bus to test launch by 2023, and then five more by the following year.

Apex also plans to prioritize selling its Aries product to commercial customers first. Apex wouldn’t share its customers’ names, but said it is experiencing “significant interest” from commercial satellite operators. Cinnamon said he expects the first deals to be with companies working in satellite imaging and Earth observation, or communications. In the meantime he added Apex is “very eager to support the U.S. government, whether it be NASA, the Space Force or other missions.”

Apex’s plans couldn’t have come at a better time considering NASA is increasingly interested in having startups and private industry foot most of the bill to get its missions to orbit. The government agency is looking to pay companies that can deliver smallsat data products, and is offering a combined $476 million in contracts over the next five years to companies that meet its demands. “Those types of contracts we would love to work on,” Cinnamon said.

Given the myriad contractors already building satellite buses, however, Apex will have to make good on its competitive advantage—manufacturing speed—to succeed. Though Cinnamon wouldn’t provide specifics on timing and costs, he said that lead time on satellite buses usually is “measured in years, and we’ll measure in months.”

Alexander Harstrick, managing partner at J2 ventures, which invested in Apex’s seed round, said he believes in Apex’s proposal.

“The easiest entrant for disruption in manufacturing is to be very precise about a very specific problem,” said Harstrick. In Apex’s case, that’s how to make satellite buses faster and more sustainably than its competitors.

The issue of sustainability is a particularly important one to consider if Apex plans to mass produce satellite buses. Lately, the trend in aerospace is to avoid sending up hefty satellites with long lifespans and instead focus on constellations of smaller satellites, sometimes in the thousands (see Elon Musk's ambitions for Starlink).

But the more satellites launch into orbit, the more potential there is for its debris to cause harm. NASA is leading the initiative to reduce space waste; it and the FCC are advising private firms to build their satellites so they can de-orbit within five years. John “Danny” Olivas, a retired NASA mission specialist and co-director of USC’s Visual Intelligence and Multimedia Analytics Laboratory, called space junk “a real and present danger,” but added, “I think generally the space community is actually pretty responsible” in handling its debris.

Cinnamon said Apex is aware of this issue and has every intention to mitigate its impact on space junk. He added that, “we view the sustainability of space and mitigation of orbital debris not only core to our mission, but core to humanity’s long term survival.”

- Outpost Space Raises $7M to Launch 'The SpaceX of Satellites ... ›

- Vast, Orbital Assembly Race to Build a Commercial Space Station ... ›

- Starburst Ventures Launches Space Startup Investment Fund - dot.LA ›

- Los Angeles Space Tech News - dot.LA ›

- Apex Founder Ian Cinnamon on the Aerospace Capital: LA - dot.LA ›

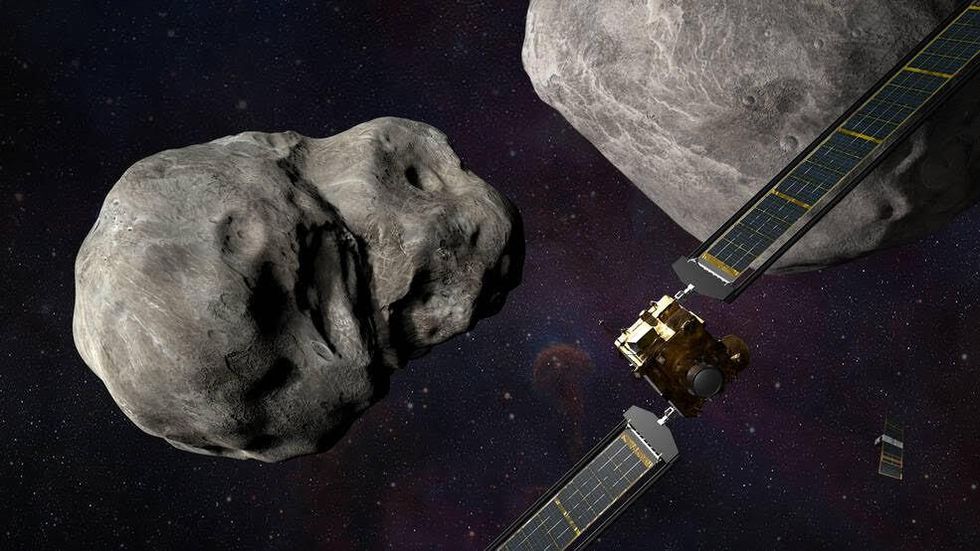

NASA’s DART spacecraft and the Italian Space Agency’s (ASI) LICIACubeNASA/Johns Hopkins APL/Steve Gribben

NASA’s DART spacecraft and the Italian Space Agency’s (ASI) LICIACubeNASA/Johns Hopkins APL/Steve Gribben