Founded by former “Shark Tank” entrepreneur hopeful James Siminoff, Ring launched in Santa Monica in 2012 and was acquired by Amazon – which has its own smart home and surveillance network ambitions – in 2018 for reportedly north of $1 billion.

Ring’s push to become cozy with the cops is spooking privacy experts and policymakers alike. It’s become a bipartisan issue – elected officials on either side of the aisle have sponsored or are lobbying bills that could reduce the scope of what private companies collect and share with law enforcement. But a bill that would block police from surveilling people’s internet habits without warrants was narrowly defeated two years ago, and there is no comprehensive federal regulation regarding what companies can – or can’t – share with police and how they should notify users.

“The ubiquity of straight to consumer surveillance technology has happened so fast and the relationships from the very start have been so cozy with police,” Electronic Frontier Foundation policy analyst Matthew Guariglia told dot.LA. “It's been so untransparent to some extent, that we really have not caught up yet.”

Amazon’s vice president of public policy Brian Huseman and Sen. Edward Markey (D-Ma.) exchanged dueling letters this week after Markey called Ring out for sharing data with police and asked for more information about the company’s privacy practices.

Huseman did not agree to several of Markey’s demands, including commitments to not accept financial contributions from policing agencies or allow immigration officials to access Ring recordings. Amazon also refuses to commit to never participating in police sting operations.

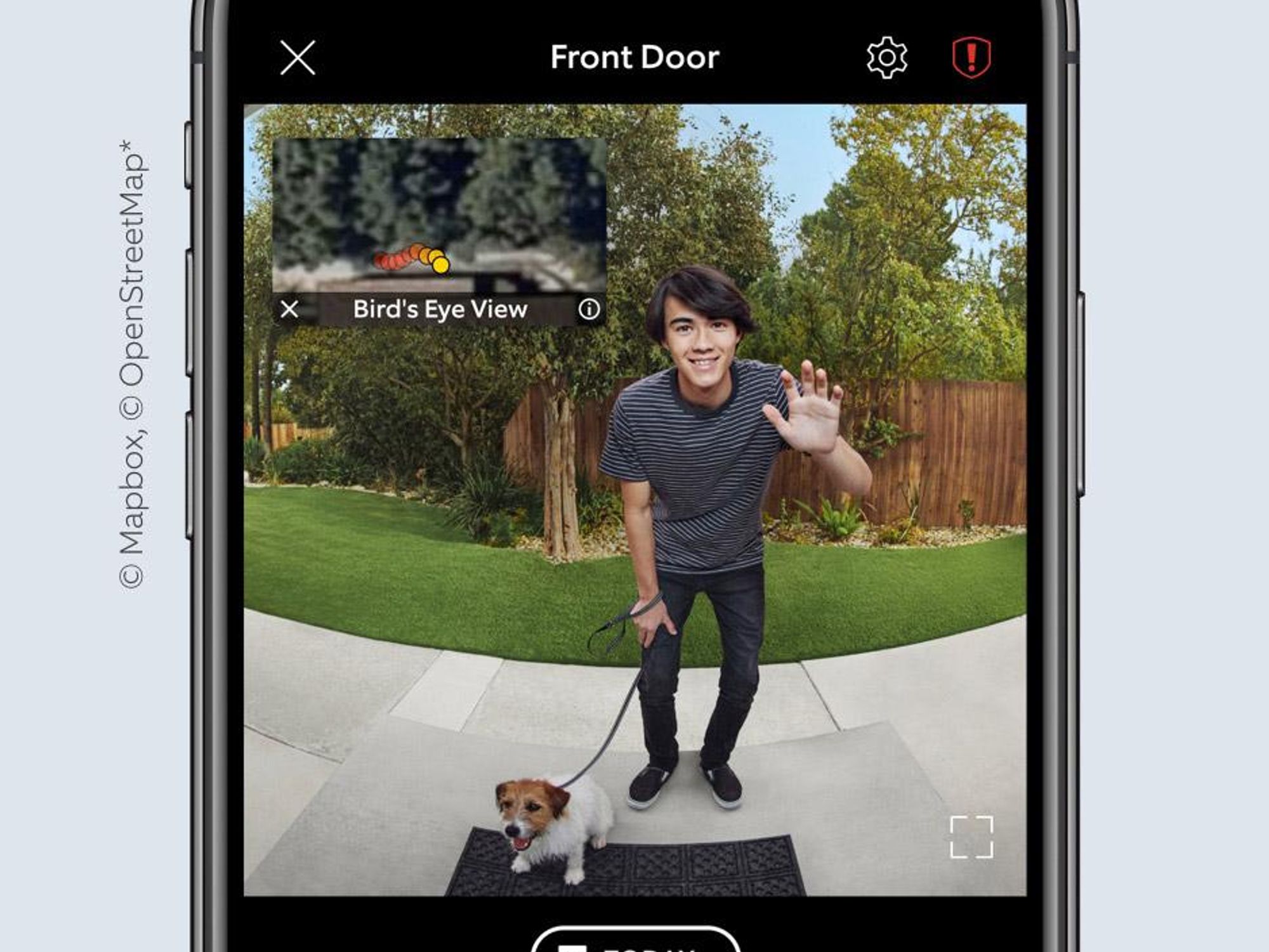

Ring's doorbell camera. Credit: Ring dot.la

Ring's doorbell camera. Credit: Ring dot.la

One of Ring’s more contentious features is its Neighbors app, which comes free with a Ring device, and its companion app for public safety agencies, called Neighbors Public Safety Service (NPSS), where police can post “requests for assistance” where they provide some details of alleged crimes and ask users to publicly comment tips or privately share footage from Ring devices.

“I agree there are a lot of potential harms that might come with that type of function,” said Max Isaacs, a staff civil rights attorney for the Policing Project at the NYU School of Law.

Guariglia said there’s seemingly no limit to the amount of footage police can get. He also noted he’s seen requests for up to eight hours. “They can use that footage in any way they want [and] they can forward it to other departments,” he said. “They might tell you they're investigating a car break-in. But what happens if your neighbor is undocumented, are they free to forward that footage to ICE?”

Ring said over 2,600 law enforcement agencies are on the NPSS platform, over a fivefold increase from 2019, growth which could in part be attributed to Ring's policy of giving law enforcement officials freebies in exchange for hawking their products. Last year, Ring Chief Technology Officer Josh Roth told dot.LA "our customer is not the police department."

Ring’s policy is that it only allows agencies to see camera footage if the owner agrees, or police get a warrant. But it says it's allowed to share video without user consent if there’s an “emergency,” which is vaguely defined as “cases involving imminent danger of death or serious physical injury to any person.”

Markey asked Huseman and Ring to clarify, but the company refused to elaborate.

In an email statement to dot.LA, Ring said, "it’s simply untrue that Ring gives anyone unfettered access to customer data or video, as we have repeatedly made clear to our customers and others. The law authorizes companies like Ring to provide information to government entities if the company believes that an emergency involving danger of death or serious physical injury to any person, such as a kidnapping or an attempted murder, requires disclosure without delay. Ring faithfully applies that legal standard."

“Police can request footage without a warrant without consent of the user, if they and Ring decide the situation was extreme enough,” said Guariglia. “I don't know who elected them the arbiters of what an emergency is, and what requires the use of emergency Ring footage as quickly as possible. But apparently, it's them.”

Ring's "Always Home Cam." Credit: Ringdot.la

Ring's "Always Home Cam." Credit: Ringdot.la

Max Isaacs worked on a December 2021 audit conducted by the Policing Project and commissioned by Ring (Isaacs told dot.LA NYU donated the $25,000 Ring paid for the study to a racial justice nonprofit) which found that more than 10 million people use Neighbors every month. He said Ring did take some of the Policing Project’s advice, including working to make the process of police requesting footage more transparent.

“What Ring has done through the audit is taking the first step; it’s modified some of its practices in a way that we think is a step in the right direction,” Isaacs told dot.LA. “What has to happen now is for policymakers to begin studying, learning from this transparency, learning how police are using this tool and creating sensible safeguards and rules for police to follow so that we can prevent some of the misuse and privacy implications that advocates are concerned about.”

Matthew Guariglia said the EFF wants Ring to add more public service groups to the app, like homeless outreach groups, fire departments and even animal control. He also said EFF recommends Ring make two key changes: firstly, turning on end-to-end encryption by default for users. People can turn this on in their app but only if they know where to find the setting and even understand the importance of encrypting their data.

Encryption “is not a perfect solution, but it's much safer and more verifiable than the case where the data is sitting on their servers and they can give it to whomever they want,” Dr. Clifford Neuman, director of USC’s Center for Computer Systems and Security told dot.LA.

Another thing the EFF says Ring needs to fix is ending default audio collection. Guariglia told dot.LA a study of Ring devices by Consumer Reports found that Ring doorbells can record audio up to a 30-foot radius, further increasing Big Brother’s range of sight.

“The cameras aren't even deployed by the government. It's individuals doing it for their own purpose, but you've got the aggregation of the data that changes the nature of surveillance that can be accomplished,” Neuman noted.

Will Ring and its competitors, including Nest, Blink, and Arlo be reeled in any time soon, or will these tens of millions of cameras scattered across the country eventually form an unavoidable mesh network of lateral surveillance that continues to foster racism and over-policing? Experts said that depends on how quickly lawmakers regulate the business. But as the first video security firms figured out ages ago, as long as people remain in fear of crime, Rings will continue to sell.

“Simply put, fear sells,” Guariglia quipped. “The more you are paranoid and afraid, the more cameras you're going to buy, the more apps you're going to download, [and] the more you're going to surround yourself with things that are going to make you even more afraid.”

Editor's note: This story was updated Friday, July 15 to reflect comments from Ring.

From Your Site Articles

Related Articles Around the Web

Ring's doorbell camera. Credit: Ring

Ring's doorbell camera. Credit: Ring  Ring's "Always Home Cam." Credit: Ring

Ring's "Always Home Cam." Credit: Ring