Peter Pham Is Not Afraid to Die. How One of LA's Preeminent VCs Became Obsessed with COVID

Ben Bergman is the newsroom's senior finance reporter. Previously he was a senior business reporter and host at KPCC, a senior producer at Gimlet Media, a producer at NPR's Morning Edition, and produced two investigative documentaries for KCET. He has been a frequent on-air contributor to business coverage on NPR and Marketplace and has written for The New York Times and Columbia Journalism Review. Ben was a 2017-2018 Knight-Bagehot Fellow in Economic and Business Journalism at Columbia Business School. In his free time, he enjoys skiing, playing poker, and cheering on The Seattle Seahawks.

As Thanksgiving approached, Los Angeles Mayor Eric Garcetti implored residents to stay home and halt all nonessential travel as COVID-19 cases skyrocketed.

But on Thanksgiving Day, Peter Pham, one of L.A.'s most prominent early-stage investors and the co-founder of Science Inc, a Santa Monica startup studio and early-stage venture fund that manages over $100 million and recently launched a $310.5 million SPAC, posted a selfie of himself atop Las Vegas' High Roller ferris wheel.

He was clutching a can of Liquid Death, the bad boy-themed canned water brand that has improbably become Science's buzziest startup. Pham guzzles six cans a day, because he says he does not trust municipal tap water.

"I'm not afraid of dying," Pham told me recently. "There's risk for everything and COVID is a risk that I feel very confident in my ability to deal with. I could be wrong and that's OK. I am OK if I fucked up and I die from it."

Pham has been transfixed by COVID since March, often tweeting dozens of times a day and sometimes much more – about his aversion to lockdowns and school closures, blockbuster treatments the government is allegedly ignoring, and the rocky vaccine rollout. He has also made it his mission to help distribute millions of PPE to medical workers.

"I like to go deep on things, like OCD-type deep," he said. "I like to learn and I like to fix things. I can get obsessed."

Pham stands out from most, but certainly not all VCs – who strive to remain as bland and non-controversial as possible, according to Tom Nicholas, a Harvard Business School professor who wrote the book, VC: An American History.

"Being neutral makes sense in an industry where investments are frequently syndicated," said Nicholas. "There's a lot of downside to being a contrarian and very little upside."

Pham says he does not care about being liked or offending others.

"It's opt-in, dude," he said. "If you don't like it, don't fucking follow me."

Pham says his tweets are a perfect reflection of his personality, which he admits can be scattered. But it is more than worth it, he says, because he is intensely loyal and "goes to the mat" for friends, colleagues, and founders that Science is backing.

"You know what you're going to get with me," he said. "You're going to get an erratic person who's passionate beyond belief."

Pham has scored the sort of exits that give him the license to speak his mind in the elite venture world, none bigger than the Dollar Shave Club, the direct-to-consumer razors and grooming startup that put Science on the map when it was bought by Unliever for $1 billion in 2016.

"Peter is definitely wired differently than most VCs I've met," said Michael Dubin, founder of Dollar Shave Club, "I think of Peter as an expert networker and fundraiser. He's highly social. He loves people. He's the first one on the dance floor, as he says on his Twitter bio."

Dubin says Pham is not the sort of investor to labor over the details of a company. Instead, Pham stands out for two qualities – he is a gifted "hype man," which is very useful when you're trying to build any company but especially consumer brands. And most of all, he possesses probably the most valuable skill in tech: The ability to quickly raise vast sums of capital.

"He is incredible at raising money," Dubin said. "When you're a VC looking to invest in companies and Peter Pham calls you, you definitely pick up the phone and listen to what he says. It doesn't mean you believe him, but you definitely pick up the call."

To Dubin, it makes sense that Pham has been consumed with trying to find light at the end of the COVID tunnel.

"The way Peter's brain is wired, it doesn't surprise me he is on the leading edge of trying to find helpful interpretations," Dubin said, before pausing to add: "It doesn't make him right. He's not Dr. Fauci."

'The Biggest Scandal in the History of COVID'

Pham talks frequently about his "research" and the hours he devotes to pouring over scientific papers even though his scientific training is limited to majoring in biology and pre-medicine during his undergraduate years at the University of California, Irvine. He planned to be a doctor but changed his mind junior year when he decided it required too much structure.

"I was premed, so I actually understand science," he said.

Pham has been especially vocal about the antiparasitic drug Ivermectin, which he went so far as to give to his housekeeper's ailing 80-year-old friend, which he shared on Twitter.

"It's a cheap drug that clearly is helping," Pham said. "That's been my crusade for the last couple of months."

A recent paper in the Journal Lancet found "limited evidence" that Ivermectin was effective in treating COVID patients. The FDA has warned people not to take the drug because it has not been tested outside of the lab.

Pham has no such patience, posting frequently that the drug needs to be widely distributed immediately.

"That will go down as the biggest scandal in the history of COVID," he declared.

Last month, amidst the chaotic vaccine rollout in L.A. County, Pham shared that he devoted a day to visiting five vaccination sites and more than 30 hours researching and talking to friends in health care.

Asked how he has so much time to devote to COVID, Pham said that he stays up until 3:30 a.m. every morning and only sleeps four hours a night.

"My partners are amazing and they know that I like to help people," Pham said. "Making money is not my goal in life, but I'm not neglecting my startups and my company."

Michael Jones, the former MySpace CEO who recruited Pham to work at Science Inc. in 2011, says he has no concerns about Pham's work habits.

"Peter has his own unique style of working, Jones said. "He complements our firm in a really unique and special way that I think benefits a lot from our investors."

'Sit This One Out;' Other Prominent Investors Push Back

In early March, Pham hosted his exclusive annual gathering of top VCs at Gjelina, a tony restaurant in Venice. The guests of honor were the suddenly very wealthy founders of Honey, an L.A. startup that sold to Paypal for $4 billion at the end of 2019. Pham hoped that the conversation would stay focused on the dinner's purpose – raising money – rather than the mysterious virus that by then was consuming people's attention.

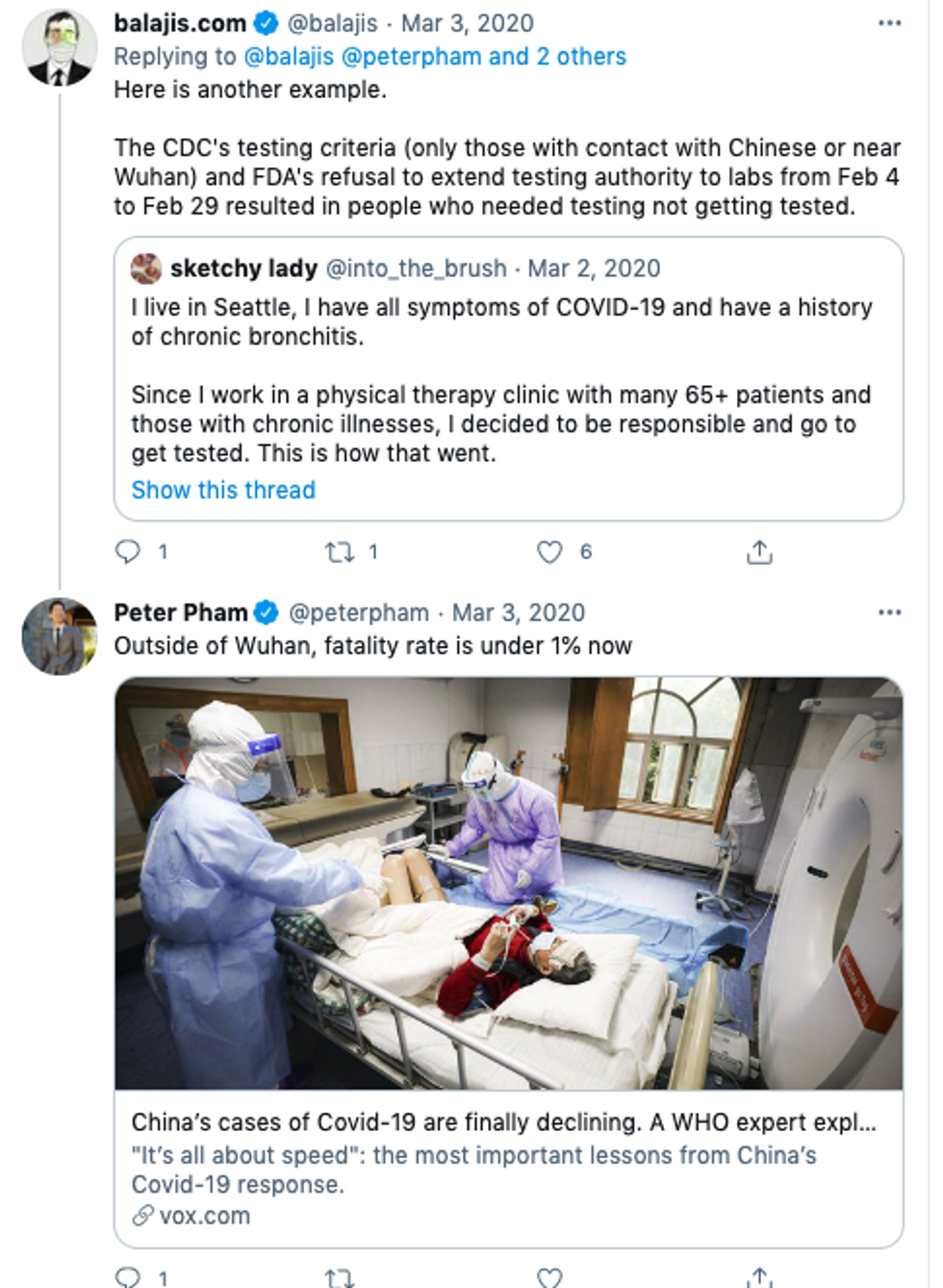

In the early days of the crisis, Pham repeatedly played down the seriousness of COVID, arguing that it only affected the old and sick, something Balaji S. Srinivasan, an angel investor and entrepreneur and former general partner at Andreessen Horowitz, pushed back against.

Pham now freely admits he underestimated the threat of COVID and he is certainly not the only one to do so, but he says the important thing is to learn from new information when it becomes available.

"I didn't think it would be that bad in March and obviously I was wrong," Pham said. "I'm not dogmatic in anything."

To Pham's credit, in March he also started raising money in the tech community to buy and distribute badly needed PPE as a founding member of C19 Coalition, which has delivered more than one billion units of masks, face shields, and other equipment.

But those early overly rosy assessments have not deterred Pham from continuing to downplay the risk from COVID, advocate for herd immunity, and accuse the media of hyping up the threat.

In August, he tweeted that the worst of the pandemic was over, when U.S. case numbers were a third what they were this month. In November, he said hospitals "will continue to be fine," a month before ICU capacity in Southern California plummeted to zero percent.

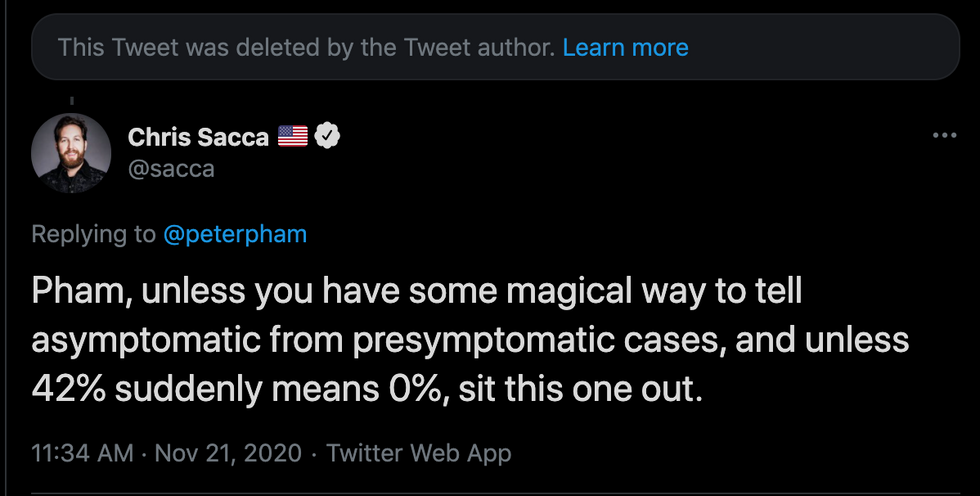

Chris Sacca, a venture investor best known for being a judge on Shark Tank who is a limited partner in Science, shot back around the time ICU was hitting 0% capacity, telling Pham to "sit this one out."

Pham says he can't recall what he was tweeting about. He deleted the original tweets that Sacca and Srinivasan were referencing.

"I should autodelete my tweets, to be honest, but I use it for search because my memory is so bad," Pham said. "I have ADHD with the memory capacity of the bottom 16th percentile of the population."

Pham does not appear to be exaggerating. Two weeks after we spoke for over an hour on two Zoom video calls, Pham had no memory of us ever talking.

"My memory is horrible," he said.

Pham says his lack of memory is one of the reasons he is perpetually upbeat.

"I'm always optimistic because I forgot what happened yesterday," he tweeted last month.

He says his lack of memory is also why he is so blunt and unfiltered.

"People are trying to create this persona online, which is weird and a lot of work and I think you have to have a good memory, and I don't have that," Pham said. "I don't care. I just say it."

The one thing Pham never talks about is family, which he says he avoids doing for privacy reasons, especially as he has gotten more involved with the sometimes shadowy world of cryptocurrency. He also won't reveal his age or the city where he grew up for "security reasons."

Pham may not fear COVID, but he lives in constant fear of being hacked.

The Embodiment of the American Dream

Pham often says he has lived the embodiment of the American dream and it is not hard to see why.

His father served as a fleet commander for the South Vietnamese Navy during the Vietnam War and in 1975, weeks after the fall of Saigon, the U.S. Navy evacuated Pham's parents and four older siblings to California.

Pham was born in a refugee camp about a month later.

The family grew up poor in a cramped one-bedroom apartment, the reason he says he has been dismayed many public schools have closed their doors during the pandemic. His parents both became social workers while the siblings took on odd jobs to put food on the table.

Pham was a straight-A student in high school and applied to only one college, the University of California, Irvine, which he picked because it was close to home.

He put himself through college, waiting tables at Red Lobster, selling computers at Circuit City and helping people install Windows operating software on their computers.

Pham found he was much more interested in tech than being a doctor and after adding a business management minor to his biology major, he bounced around 13 enterprise software and hardware startups for the first nine years of his career in business development.

Biz dev, as it is known, is largely sales and marketing. Above all, it requires hustle and building and maintaining big networks of individuals who can help your company – things Pham discovered he could do with ease.

His first major success came in 2005 when his friend Alex Welch recruited him to do biz dev at Photobucket, an early digital photo sharing platform that is now mostly forgotten. Pham was hired as the fifth employee and three years later News Corp. acquired the company for $300 million.

Pham went on to start BillShrink, a website to help consumers save on cell phone bills, credit cards, and gas. It was eventually bought by Mastercard.

After those exits, Pham had the credibility to raise major sums of capital from top Sand Hill Road firms — and that is exactly what he did in 2010 when he teamed with serial entrepreneur Bill Nguyen to start Color – named for their love of the Apple logo — the photo-sharing app.

"He's probably the best sales person I've ever met in my life, which is saying a lot because people think I'm a pretty good salesperson," Pham said. "He can convince you of anything."

Pham and Nguyen quickly amassed $41 million from Sequoia Capital, Bain Capital and Silicon Valley Bank before they ever launched a product. That was far more than Instagram, which was founded the same year with just half a million in seed funding, or about what Color spent just on acquiring the domain names color.com and colour.com.

Color also rented a cavernous office with a hand-built skateboard ramp in Palo Alto with room for 160 employees even though they had fewer than 40.

The New York Times featured the company as a prime example of another bubble in start-up investing. (It also warned about Airbnb in the same article, which had a much better fate.)

Unlike Instagram, which was built around users seeing photos of accounts they chose to follow, Color users viewed photos by location. But it turned out that was not what users wanted at all and the 2011 launch was a dud. Nyugen fired Pham three months later. Pham said he quit.

Apple bought Color in 2012 for $7 million amidst bizarre allegations of an abusive work environment, which was not only far less than the $167 million valuation Color had raised at in 2010 but also a long ways away from the $200 million Google had offered to buy the company in early 2011, according to Techcrunch.

Reflecting on his Color tenure now, which is omitted from his official bio, Pham says he barely knew Nyugen before they started the company – a mistake he would never make again – and describes their partnership as a "shotgun marriage."

"It wasn't a marriage that lasted," he said. "We were different people."

Pham defends the premise of Color as ahead of its time, pointing out that Snap launched a map feature two years ago that emulated what Color was trying to do.

"We were just early, and of course execution of this thing," Pham said. "Shit happens. Startups fail. It just didn't work."

But it did not take Pham long to get another job offer. Three months after his departure, Pham bumped into his old friend Jones at the Lobby Conference, an invitation-only consumer and enterprise tech gathering held annually in Maui.

They had been kicking around the idea for years of creating a Santa Monica version of Bill Gross' longtime startup studio, Idealab, which is in Pasadena.

"I wanted to do Idealab, but on the west side of town, because I like the beach," Pham said.

Up to that point, Pham and Jones had been consumed with other startups, but now they were both jobless and Pham wanted to move back to L.A., where he grew up and his family lived.

"Most people thought it was insane to leave the gold rush in the valley at that time," Pham said. "But what we wanted to do is be closer to building the business, not just writing the check."

Jones says he had no reservations about teaming with Pham, despite him only being a few months removed from being fired from Color.

"I wasn't at Color and I don't really know any of the background of Color," Jones said. "What I knew is that I knew Peter for a very long time."

Jones also recruited his longtime attorney Greg Gilman and former Myspace colleague Tom Dare to round out the founding team. Science Inc. launched with $10 million in venture backing from investors including Google CEO Eric Schmidt and another $30 million from the Hearst Corporation.

The now defunct Gawker tech gossip spinoff, Valleywag, marvelled at how quickly Pham was able to escape the Color fiasco.

"Why the hell are people still giving this guy money?" reporter Sam Biddle asked. "In just a couple short years, Pham has failed upwards, meteorically, from industry laughingstock to managing hundreds of millions of dollars."

But Pham soon proved the doubters wrong.

In its first year, Science had the sort of breakout success that it has never been able to top in the decade since.

Science incubated a small startup that sold razors and grooming supplies direct to consumers with quirky marketing campaigns with a $100,000 check. The next year, Kleiner Perkins Caufield & Byers led a $1 million seed round. In 2016, Unilever acquired Dollar Shave Club for $1 billion and yielded its founder, Dubin, a reported $200 million payday.

"Peter was instrumental in helping us fundraise," Dubin said. "He knows the art and science of raising money. He's extremely connected. We just would not have raised the money we did if it had not been for him."

Science has also scored big wins with DogVacay, which merged with its larger competitor Rover in 2018, and FameBit, an influencer marketing platform that was acquired by Google in 2016 before being shut down last year.

These days the firm's buzziest startup is decidedly low tech. Liquid Death, featuring the slogan "Murder Your Thirst," packages Austrian mountain water in aluminum cans. Pham says he was drawn to Liquid Death after a friend showed him the brand's edgy Facebook page.

Science incubated the brand in 2019 and led the $2.26 million seed round at a pre-money valuation of $5 million. In September, Liquid Death raised another $23 million Series B funding at a pre-money valuation at $82 million.

Mike Cessario, the creative director turned founder and CEO of Liquid Death says the first time he met Pham at Science's offices he struck him as "a really smart guy who talks a million miles a minute."

"Peter has stepped up with us to make sure we can get the best deals we can get where we are not being taken advantage of by other investors," Cessario said.

Pham is rarely seen without a tall can of Liquid Death by his side. He says he consumes six a day because is worried about drinking the tap water where he lives.

"I don't trust the water in Manhattan Beach," Pham said. "It's got PFAS in it – plastics forever. If you don't know what that is, Google it. It's going to blow your mind."

Unlike with Nyugen, in Jones Pham says he has found someone who he will be friends with for life. Pham says he has finally found the role that perfectly suits his unique personality. At Science, he is in-charge of business development. Crucially, he has no direct reports.

"I don't like managing people," Pham said. "I was CEO once. It's not my thing."

Last month, Science Inc. announced that it was launching a $270 million SPAC to focus on direct-to-consumer, mobile and entertainment companies.

'It's All Over in 60 Days'

These days Pham has been traveling to Miami, which comes with the dual advantages of being a place unencumbered by the lockdowns he hates and also home to a rapidly growing startup scene that he says reminds him of L.A. 10 years ago. Ever the networker and promoter, Pham hosted a sunset cruise there this month for tech founders and investors where they sipped on Liquid Death.

Pham continues to advocate for Ivermectin and has also been pushing the yet-to-be-approved Novavax Vaccine. He enrolled in the vaccine's phase III trial and says it is his "favorite" vaccine because it is easier to store and can be used on immunocompromised patients.

Far from a distraction, Pham says his passion about COVID and helping secure PPE has brought the unintended effect of further expanding his professional network.

"It opened up a whole new network of entrepreneurs and spaces and industries that we're now looking into investing in," Pham said. "It all comes full circle. It turns out if you do good things in life, you get rewarded."

While so many Americans are relentlessly dreary after nearly a year of the pandemic, Pham is more sanguine than ever.

"I still am optimistic it's all over in 60 days," he tweeted this month.

"We will all be having easter dinner with family," he added last week.

Lead image by Eduardo Ramón Trejo.

Editor's note: This story has been updated with Science's closing amount for its SPAC and a clarification from Pham on Color.

- Science Inc. Makes $270 Million SPAC Debut - dot.LA ›

- Liquid Death Files Paperwork to Raise $15 Million - dot.LA ›

- How Science Inc CEO Mike Jones Stays Ahead of the Trends - dot.LA ›

Ben Bergman is the newsroom's senior finance reporter. Previously he was a senior business reporter and host at KPCC, a senior producer at Gimlet Media, a producer at NPR's Morning Edition, and produced two investigative documentaries for KCET. He has been a frequent on-air contributor to business coverage on NPR and Marketplace and has written for The New York Times and Columbia Journalism Review. Ben was a 2017-2018 Knight-Bagehot Fellow in Economic and Business Journalism at Columbia Business School. In his free time, he enjoys skiing, playing poker, and cheering on The Seattle Seahawks.

Image Source: Revel

Image Source: Revel