Density Was Designed to Keep Lines Short. It Just Raised $51M to Keep People Safely Distanced

Ben Bergman is the newsroom's senior finance reporter. Previously he was a senior business reporter and host at KPCC, a senior producer at Gimlet Media, a producer at NPR's Morning Edition, and produced two investigative documentaries for KCET. He has been a frequent on-air contributor to business coverage on NPR and Marketplace and has written for The New York Times and Columbia Journalism Review. Ben was a 2017-2018 Knight-Bagehot Fellow in Economic and Business Journalism at Columbia Business School. In his free time, he enjoys skiing, playing poker, and cheering on The Seattle Seahawks.

When CEO Andrew Farah co-founded Density in 2014 with a team of Syracuse graduates, their initial goal was to avoid waiting in line at their favorite downtown coffee shop. Syracuse averages 104 feet of snow a year and they got tired of trudging through the cold only to wait 15 minutes for Sumatra drip coffee and bagels. Being engineers and designers, they thought there had to be a better way. They spent the next few years building a system that, as it turned out, is perfectly suited to the current COVID-19 era: A way for companies to monitor precisely how many people are occupying a given space.

"We don't take pride in the fact that a pandemic has accelerated distribution," Farah said. "But we take pride in the fact we can help in a small way to keep people safe."

Since COVID, Density has seen revenue shoot up more than 500%. Prior to the crisis, the company had seen growth of around 40% each quarter. Warehouses, grocery stores, meat processing plants and casinos all signed-up, eager to find a way to limit capacity.

Density announced Tuesday it has raised $51 million in Series C funding led by Kleiner Perkins, with participation from 01 Advisors, Upfront Ventures, Founders Fund, Ludlow Ventures, Launch, and DTA. Former MLB All-Star Alex Rodriguez also invested. Prior to this round, Density had raised $23 million, bringing total funding to date to $74 million.

Before the pandemic struck, Density saw considerable demand from companies who wanted to increase security and better utilize their office space. An estimated $1 trillion of rented office space sits empty in the United States and Farah says employees and managers are not very good at knowing what space they need and what is a waste of money.

"Most organizations were largely flying blind about how they design buildings," said Farah. "Buildings have been designed based on 150 or 200 square feet per employee, but that's just a best guess or observation."

When Verizon bought Yahoo in 2017, it used Density to figure out which desks and conference rooms it could get rid of to save on rent. Clients also include a who's who of tech companies such as Facebook, LinkedIn, Uber, Salesforce, Google, Amazon and Uber as well as Nike, Booz Allen Hamilton and the U.S. government.

While some might see the technology as intrusive surveillance, Farah says Density actually provides more privacy because its proprietary depth sensors and deep learning algorithms do not use anything that could identify who a person is, making companies reliant on traditional surveillance cameras that record a worker's every move.

"The most sophisticated companies in the world don't want to spy on employees," said Farah. "They want to preserve employee privacy."

Mark Suster, managing partner of Upfront Ventures, says he was drawn to Density as part of his thesis that computers are better at making decisions about the physical world than humans. He's invested in more than half a dozen companies along those lines including Nanit, which makes smart baby monitors, and Ring, a smart home monitoring system that was bought by Amazon for more than a billion dollars in 2018.

"Our investment in Ring was really about computer vision because Ring's initial selling point was, 'it's not just a camera for your front door but it has the ability to interpret the surroundings around you'," Suster said. "It can say if it's your dog, or leaves or someone who shouldn't be in front of your house."

Suster sees similar promise in Density, which he says can do everything from helping airlines board planes more efficiently to making sure restaurants and hotels are deploying staff when they are needed most.

"Ultimately, we're an enterprise software company," he said. "We allow people to predict how people are going to move around spaces. And people have started signing multimillion dollar contracts."

Interestingly for a company that helps other companies better utilize office space, Density has been fully distributed since 2014, with 50 employees spread out across five countries and 15 states.

"I had wondered if we should all be in the same place," said Farrah, who is now based in San Francisco.

Ben Bergman is the newsroom's senior finance reporter. Previously he was a senior business reporter and host at KPCC, a senior producer at Gimlet Media, a producer at NPR's Morning Edition, and produced two investigative documentaries for KCET. He has been a frequent on-air contributor to business coverage on NPR and Marketplace and has written for The New York Times and Columbia Journalism Review. Ben was a 2017-2018 Knight-Bagehot Fellow in Economic and Business Journalism at Columbia Business School. In his free time, he enjoys skiing, playing poker, and cheering on The Seattle Seahawks.

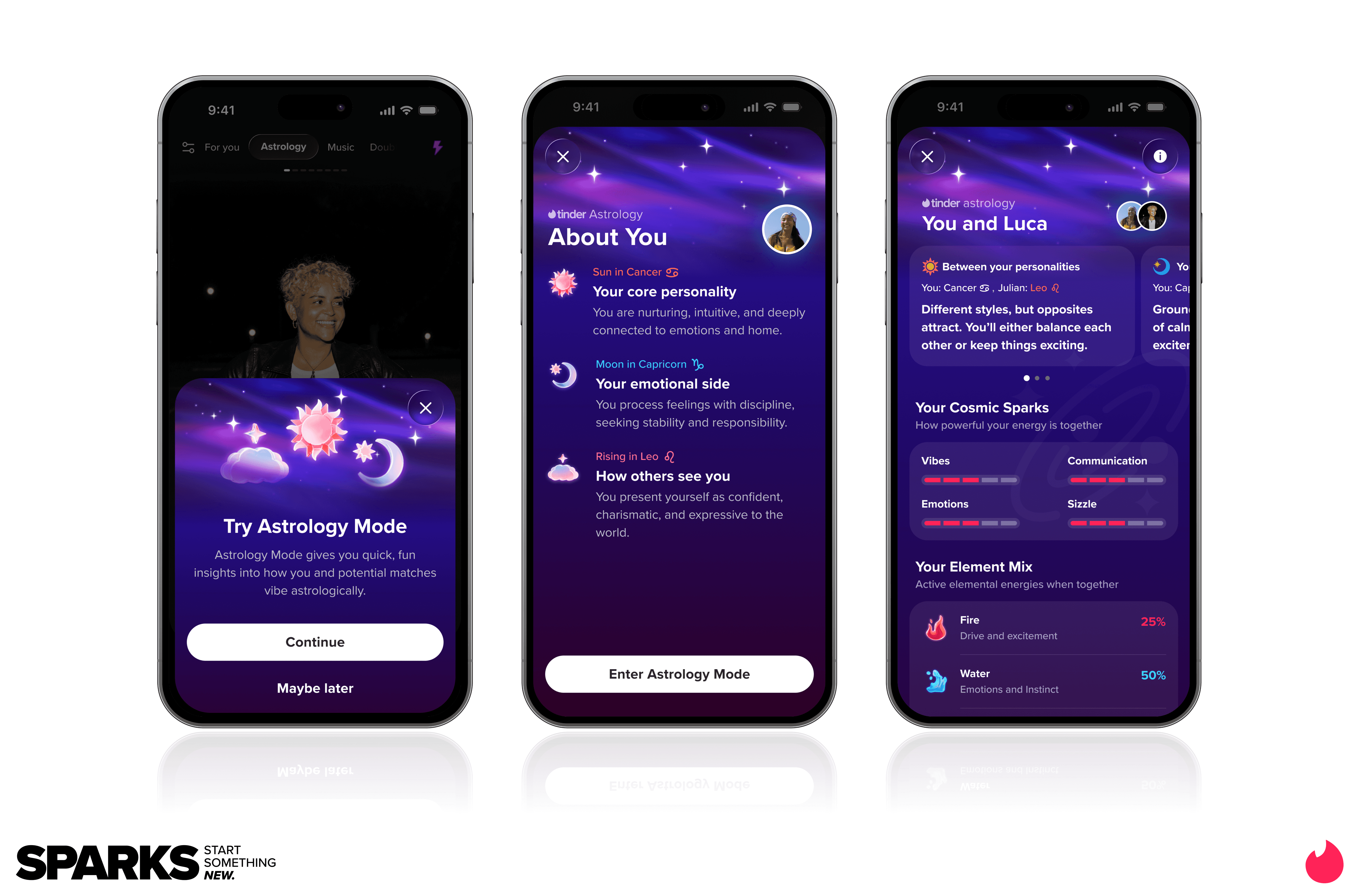

Match Group and Tinder CEO Spencer Rascoff

Match Group and Tinder CEO Spencer Rascoff Image Source: Tinder

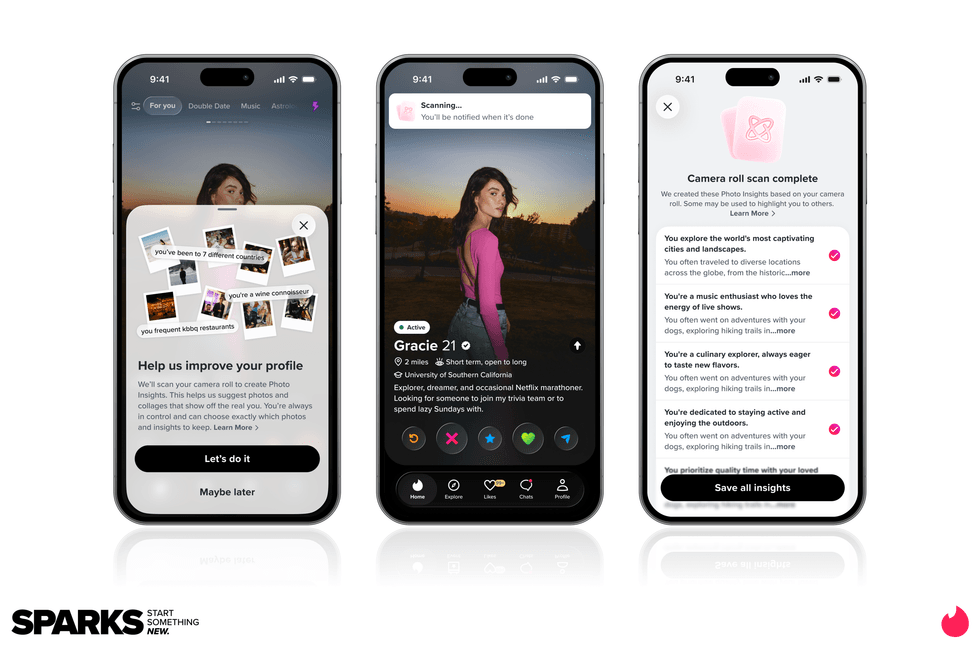

Image Source: Tinder Image Source: Tinder

Image Source: Tinder Image Source: Tinder

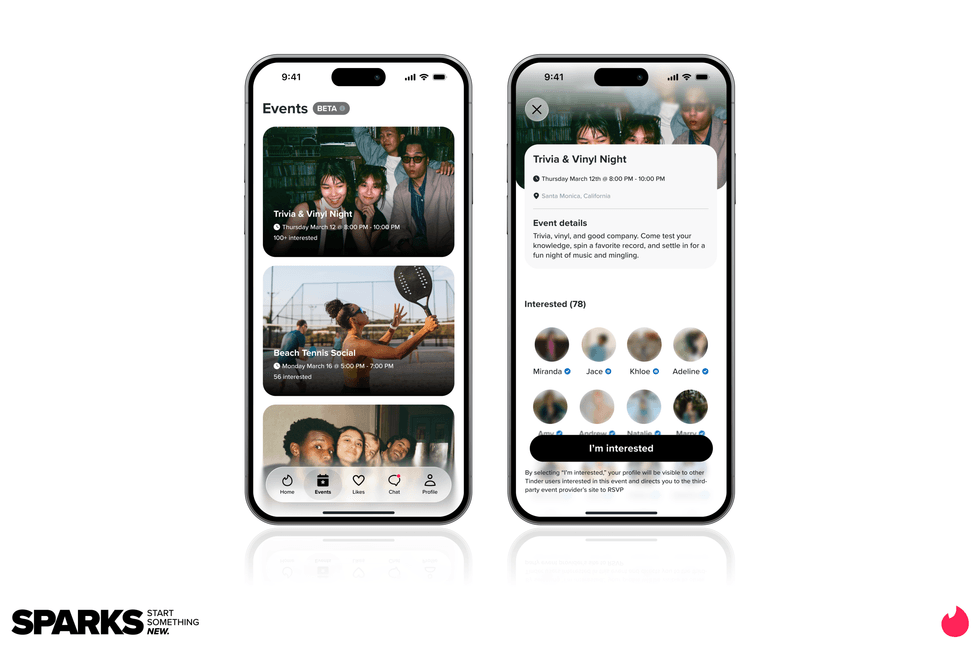

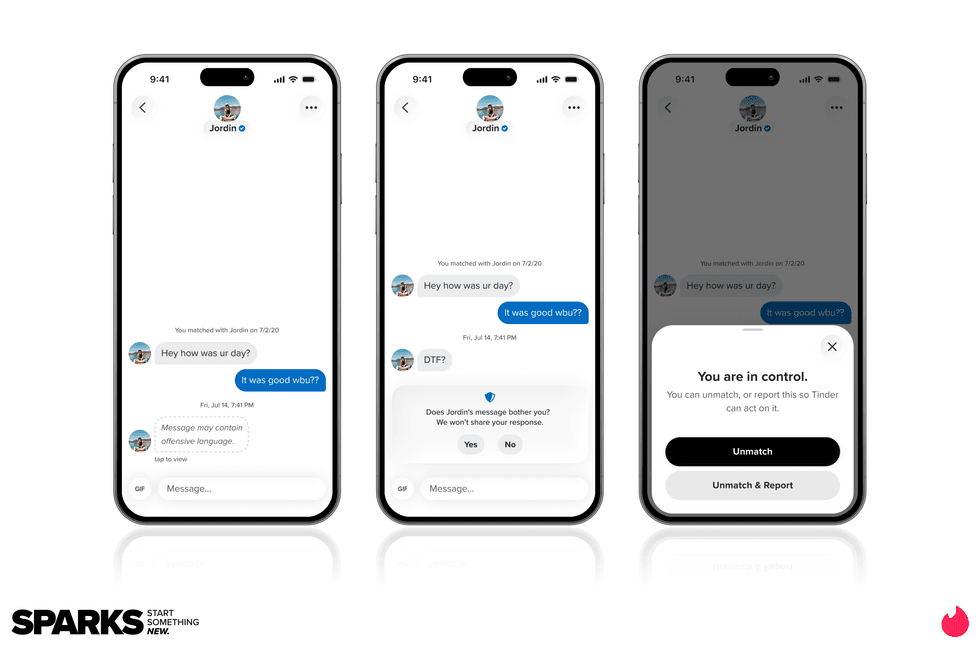

Image Source: Tinder Image Source: Tinder

Image Source: Tinder

Image Source: Revel

Image Source: Revel