Rental Startup PocketList's Rapid Rise and Fall

Francesca Billington is a freelance reporter. Prior to that, she was a general assignment reporter for dot.LA and has also reported for KCRW, the Santa Monica Daily Press and local publications in New Jersey. She graduated from Princeton in 2019 with a degree in anthropology.

Armed with nearly $3 million, a list of prominent investors and tens of thousands of users, the apartment rental platform PocketList looked like a startup poised to take off.

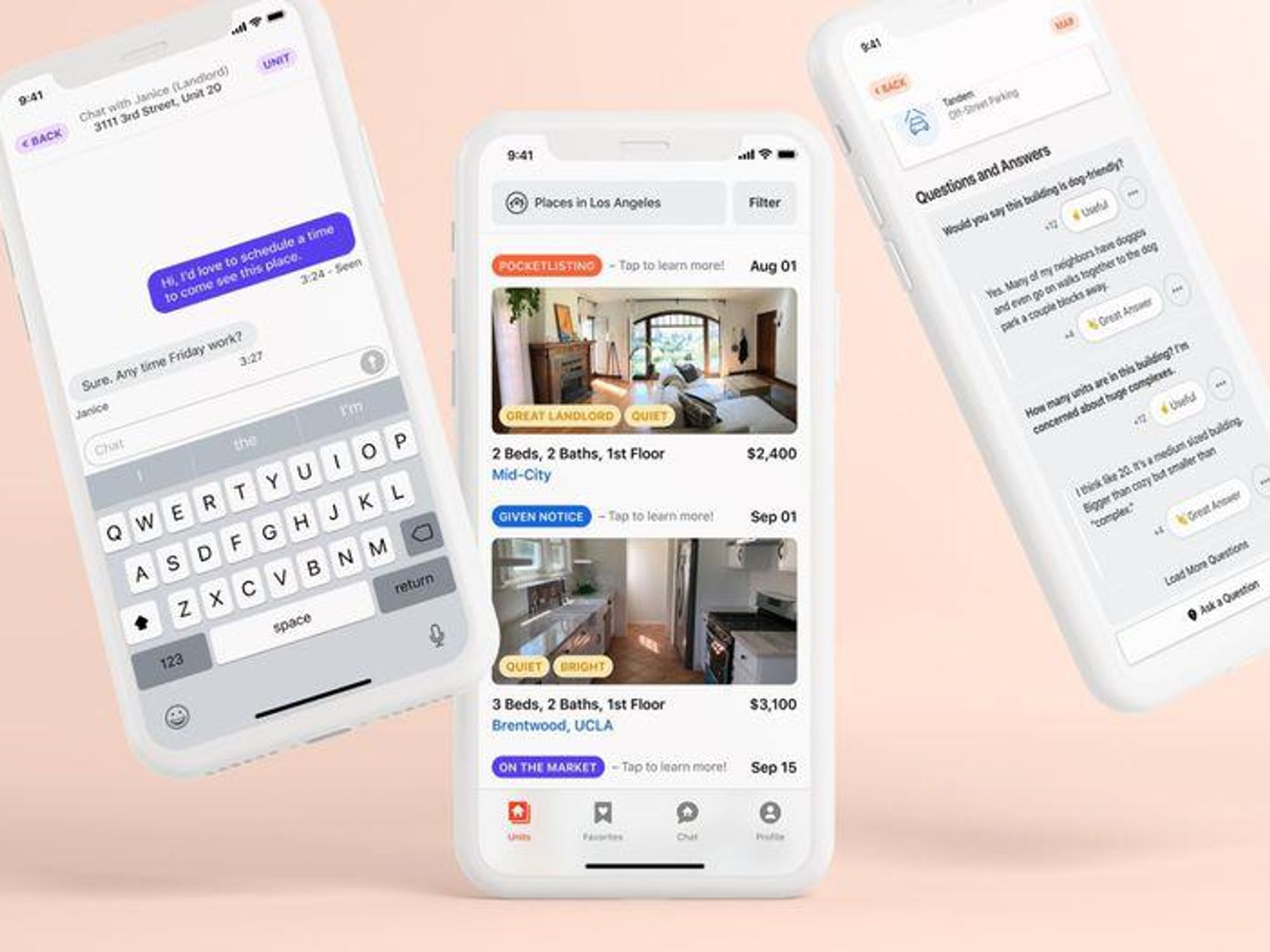

CEO and co-founder Nick Dazé touted the proptech software that let potential renters get an inside peek at apartments before being listed as technology that "turned the entire rental market on its head." He sold it as a way for landlords to save billions of dollars by cutting down turnover time between tenants and assured renters access to honest, up-to-date information about units before they went online.

Investors — who poured a record amount of money into seed startups last year — hardly needed convincing. Dazé closed a $2.8 million seed round last April led by David Sacks' Craft Ventures.

"It's no surprise that renters have flocked to the service," said angel investor Spencer Rascoff, co-founder of Zillow and dot.LA, in announcing the raise.

By July, PocketList had unveiled the app in Los Angeles with plans to launch in San Francisco and San Diego by the fall. Seattle, Chicago and New York were next.

Users could rate apartment features like natural lighting and parking in the neighborhood. There was a question and answer page for past tenants to field concerns and a chat function for landlords and prospective renters. The idea was to make renters feel like they had unvarnished insight into a unit, much the way Yelp lets users rate restaurants.

But the rollouts in new cities never came. Even before PocketList went live, renters across the country stopped signing new leases as the pandemic cast a pall over the economy. Landlords — now navigating eviction moratoriums and mounting bills — didn't have the money or the inclination to spend on new apps, Dazé said.

In the last week of April, the CEO and his co-founder Julian Vergel de Dios gave notice to eight remote employees and around 20 investors that the company would be closing operations for good.

"I spent from February until last week fundraising," Dazé told dot.LA during the first week of May. "The ultimate pause of us beginning to wind things down is that we struck out on fundraising and few very, very large customer deals we've been working on for several months fell through."

Dazé attributed PocketList's undoing to the declining renters' market and a reeling economy that kept many landlords from buying in. But in the world of venture deals, losses don't always mark the end of a company. It's the absence of investor faith.

"For a lot of seed investors, it's almost like buying lottery tickets," said UCLA Anderson School of Management professor Olav Sorenson.

"The odds of it paying off are low, but if it does pay off, you could make a lot of money," he said.

Investing capital in early-stage startups is risky and uncertain. It's nearly impossible to collect data on startups that fold given that most close shop quietly, according to Pitchbook spokesperson Kayla Gordon.

But, according to Sorenson, roughly half of all startups that raise seed money will close a Series A. The seed round supplies entrepreneurs with enough money to prove to investors their business can be successful.

That metric of success depends on investors. Most venture-backed companies in this stage don't turn a profit, but some can show enough potential for growth to entice investors back.

The Pandemic and Proptech

Investors' appetite for early-stage startups waned a bit last year, with these riskier companies pulling in $44 billion in capital compared to $47.1 billion in 2019, according to Pitchbook data.

It was a particularly rough year for proptech companies. The industry was hit harder than other parts of tech, such as ecommerce, which flourished during the pandemic as consumers moved online. Venture investments in real estate technology companies plummeted by half to $9.1 billion globally in 2020 compared to 2019, according to Pitchbook.

Most of that drop off came from flexible and co-working office spaces, said Pitchbook analyst Zane Carmean. The stay-at-home economy dried up demand for office rentals.

"A lot of that has to do with the fact that WeWork required a large injection of capital from Softbank and core investors after the failed IPO in 2019," Carmean said by email.

Other real estate tech startups kept their footing. Carmean pointed to a boom in housing demand from young coastal workers moving to the Midwest, South and Mountain West as remote working took hold.

Inside other real estate companies, though, research and development teams were the first to cut spending, said Marcelino Diaz, an analyst focused on proptech at Plug and Play Ventures. With the market dwindling, they didn't have spare cash to experiment with new technologies.

Instead, they were spending on tech that played into pandemic needs.

"Offices and retail were looking at how startups could come to help with sanitization, space optimization and most importantly, social distancing," Diaz said.

Investors backed startups like L.A.-based OpenPath for its touchless entry systems designed to reduce face-to-face contact inside office buildings and elevators. Diaz's firm invested in virtual and augmented reality startups like Avatour and Giraffe360, whose camera devices and software helped real estate managers move tours online. And he kept an eye on startups whose UV light technology promised cleaner, disinfected commercial spaces.

"It was a pivot in terms of where investments went," he said.

PocketList's founders anticipated their app would carve out its own spot in the changing market. But the demand for rental units in coastal cities — the platform's target audience — was shaky.

Pitching the Platform

In 2018, Dazé and Vergel de Dios were coming off 86 venture rejections for their startup Block, a Chrome extension for apartment hunters to sort and share listings with roommates. Dazé admitted the concept was tricky to explain, which he said, is "probably why it didn't work."

They scrapped the software and built a new prototype each month until landing on the idea for PocketList in July of 2019. In the early days, the co-founders operated the service manually through Google Forms and email, matching renters eyeing apartments in each other's neighborhoods.

"I was on my computer 24/7, three-year-old daughter climbing on my back," said Dazé, who was also consulting for Clutter, a storage and moving startup with offices in L.A. "You make it work."

Eventually, he told Clutter's CEO, Ari Mir, he was quitting the job to build his company full time. He asked Dazé for a demo and quickly became PocketList's first investor in its pre-seed round.

"Basically we raised about a million bucks that weekend," Dazé said.

Mir's investment "got the ball rolling" and a few investors who turned down the pitch for Block even chipped in. The pair soon pulled in a new roster of investors for a seed round about six months later: Abstract VC, Wonder Ventures and angel investor Rascoff.

User sign-ups and engagement had been almost doubling month over month and at its height, about 75,000 renters used the app. The platform was free for renters, instead relying on landlords to pay a fee to receive notifications about how often users listed their properties.

But by the time their funding round closed, it was mid-April of 2020 and the economy largely shut down as stay-at-home orders tightened.

"An incredibly prominent investor of ours who has a large audience — a day after lockdown — called me and scared the shit out of me," said Dazé. "He's like 'You need to batten down the hatches.'"

Dazé terminated the company's office lease in Playa Vista and cancelled software subscriptions. He cut monthly spending back by 30% without laying off a single employee.

"If we hadn't done that, we may have ultimately failed earlier," he said.

The company scrambled. It introduced paid features like instant messaging (which later became free) and experimented with new pricing models for landlords. Despite the changes, Dazé said, "every single interaction in our platform slowed down a lot."

He made the call to close the business after a series of rejections for his next funding round. A few undisclosed customers also pulled out of expected deals. On April 29, he and Vergel de Dios broke the news to their eight employees during a Zoom meeting. That afternoon, they emailed investors.

Craft Ventures and Wonder Ventures could not be reached for comment.

"Our bank account isn't at zero," Dazé said. "We're not shutting down shop in a panic because we're running out of money, but there's not enough money for us to do anything dramatic like pivot the company."

Though he would not disclose how much capital remains, Dazé told investors "not to expect anything" back. He'll distribute whatever remains based on the amount each investor contributed.

The CEO was tight lipped about his next moves, but hinted at a potential deal that may acquire the company's software. And he's confident new companies — if not members of his own team — will try their hand at a similar technology.

As for the proptech market, commercial real estate is already picking back up as companies forecast returning to the office. In L.A., leases hardly got cheaper over the past year.

"I consider this a timing issue, like most great failures," said Dazé.

He chalks most of it up to COVID-19. In a world without it, he said, "things would have turned out very differently."

Editor's note: An earlier version said Daze had been working for several weeks to strike a deal with customers, it in fact had been months. This article has also been updated to clarify the total amount raised.

Francesca Billington is a freelance reporter. Prior to that, she was a general assignment reporter for dot.LA and has also reported for KCRW, the Santa Monica Daily Press and local publications in New Jersey. She graduated from Princeton in 2019 with a degree in anthropology.

Image Source: Revel

Image Source: Revel