Sense and Stability: Artists Take AI to Court Over Copyrights

Samson Amore is a reporter for dot.LA. He holds a degree in journalism from Emerson College. Send tips or pitches to samsonamore@dot.la and find him on Twitter @Samsonamore.

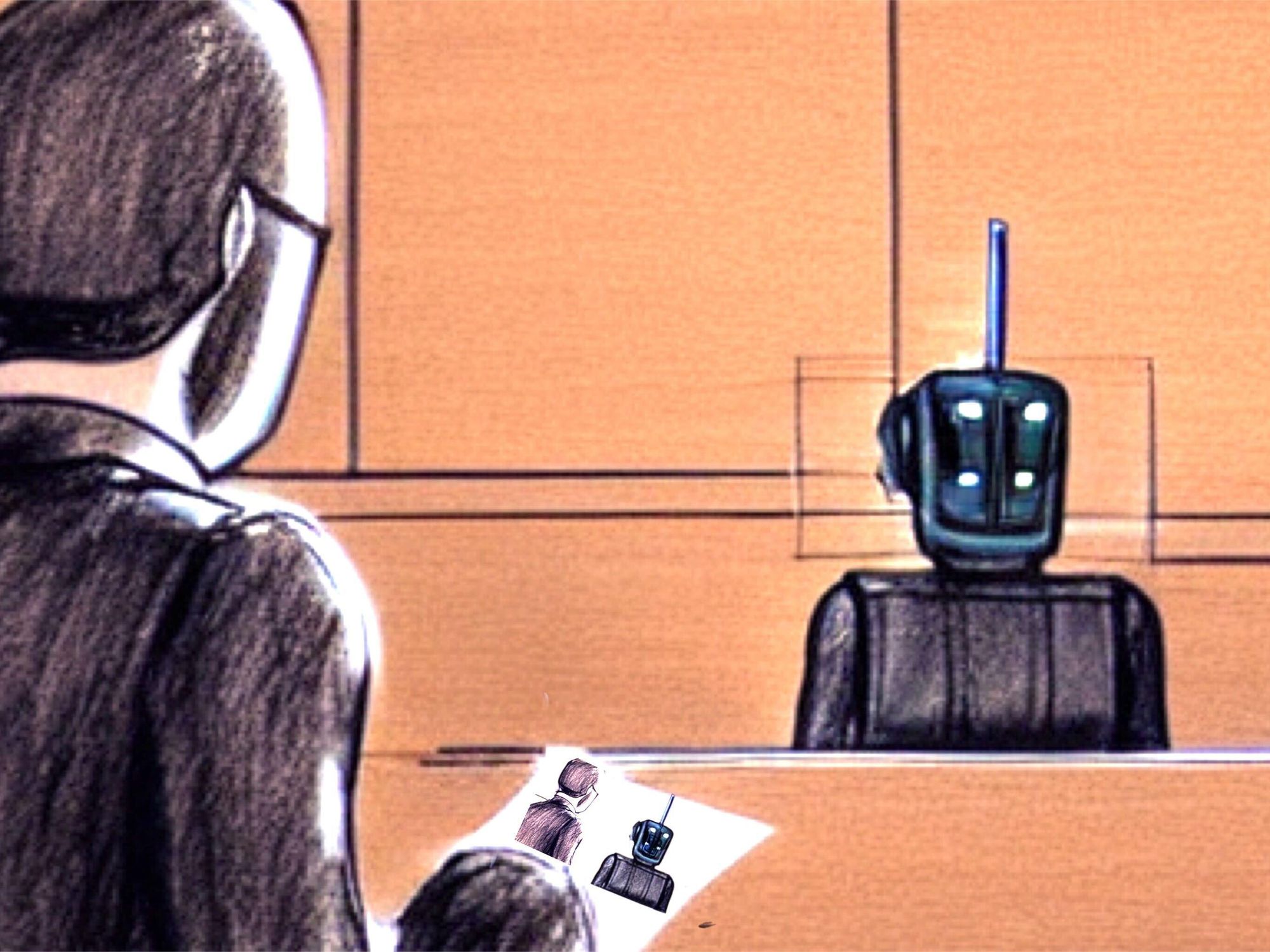

Last week, San Francisco-based artist Karla Ortiz, alongside two other artists – Sarah Andersen and Kelly McKernan – filed a class action lawsuit against AI art generators Midjourney and Stable Diffusion, as well as online art platform DeviantArt, for allowing their AIs to copy their work.

Hollywood-based DeviantArt launched its own tool called DreamUp last November, under the promise that it’d create AI art “safely and fairly.” Typically DeviantArt is used as a digital portfolio tool for artists; it’s being sued here because it allegedly allowed AIs including those made by Midjourney and Stable Diffusion to infringe on copyright. It should be noted that DeviantArt has come under fire in the past for allowing companies to profit from copyrighted images without compensating the artists.

The plaintiffs claim that three AI services created by these companies work via Stability's Stable Diffusion Software Library. According to the suit, Stable Diffusion’s training model "scraped" the internet for millions of pictures–many of them copyrighted and used the images teach the AI to reverse-engineer art. Thus, any resulting image generated by an AI trained on Stable Diffusion is inherently derivative and violates copyright, the plaintiffs argue.

The lawsuit also accuses DeviantArt of “crowding out human artists” by letting AI art onto the platform.

There’s a growing community of artists that are strictly against allowing AI to create art, mainly because to train the AI to create new art, you have to feed it existing works. Many creators, including the three suing, have seen their own copyrighted artwork be used as part of the model that trains an AI to generate new art, which raises the question – is that copyright infringement?

Unfortunately for both sides, each has a compelling argument.

Opponents of AI argue yes, and the lawsuit claims that “Stable Diffusion contains unauthorized copies of millions—and possibly billions—of copyrighted images… made without the knowledge or consent of the artists.”

In a Jan. 13 post explaining the lawsuit, attorney for the plaintiffs Matthew Butterick argued that even if “nominal damages” were applied and valued each allegedly stolen artwork at $1, “the value of this misappropriation would be roughly $5 billion,” more than the largest art theft in history (read “Master Thieves” for more on that heist). He pointed out that Stable Diffusion’s parent company Stability AI has admitted that its AI models aren’t fully licensed, which has so far been standard. We’re so early into the adoption of AI art generators that there’s very few legal guardrails yet, though this case could be the first if the artists win.

In his argument Butterick called AI art generators a “21st-century collage tool” and called Stable Diffusion “a parasite that… will cause irreparable harm to artists” by pushing them out of the market.

Proponents of AI, of course, disagree.

A group of anonymous “tech enthusiasts uninvolved in this case and not lawyers” created a website to rebuke Butterick’s claims, and they argued “the rights of creators are not unlimited,” and pointed to fair use doctrine. The response claimed the artists suing are doing so because they’re just so freaked out by AI art existing that they “fear and resist it.”

The anonymous pro-AI folks also argue that AI art tools don’t actually create image copies; they generate new art based on existing training data – which may or may not contain art the plaintiffs have created, but either way that’s fair use.

In a Twitter thread last weekend Ortiz called AI media models “deeply exploitative.” She added, “I am proud to do this with fellow peers, that we’ll give a voice to potentially thousands of affected artists. I'm proud that now we fight for our rights not just in the public sphere but in the courts.”

Additionally, in a recent New York Times op-ed, Andersen pointed out that her art had been co-opted by the alt-right before the rise in AI art’s popularity, but expressed concern that AI made it even easier to imitate her work by using her name as a keyword. Now, anyone could create a comic in her signature style without any artistic skill at all, in a matter of minutes. And to the untrained eye, it might look like Andersen drew it.

In a tweet Monday, McKernan posted a list of “hundreds of artists” whose work has been used to train generative art AIs, and asked creators to join the class action if they saw their name.

Butterick declined to comment. Attorneys for the defendants didn’t immediately answer a comment request. But in his post Butterick acknowledged that it is difficult to pinpoint exactly when an AI copies art, partly because of the “layer of magical misdirection” of text prompts.

In a recent blog post, intellectual property lawyer Andres Guadamuz noted that if Butterick can’t hold up examples of artwork that directly copied his clients’, then his odds of winning the case are slim.

“Every output image is a derivative of every input, so following this logic, anyone included in the data scraping of five billion images can sue for copyright infringement. Heck, I have quite a few images in the training data, maybe I should join,” Guadamuz joked.

Charles Arthur, a former technology editor at The Guardian who now runs the tech blog Guadamuz’s post appeared in, called the lawsuit a “total nothing [burger].” He added he’ll be following the trial “to its hopefully early demise.”

Separately, artists in Italy have started a GoFundMe petition to push EU institutions to “regulate AI training and protect our data.” It’s raised just over $25,000 of its $75,000 goal so far.

Others observing the scene said this lawsuit could be the first of many to come. Intellectual property lawyer Michael Kasdan said he’s been questioning how the U.S. Copyright Office could get involved in the AI art debate – specifically to decide whether or not AI-generated images can be protected by their own copyrights. That’s an interesting question to consider. Who’d hold that copyright… the AI? The company that owns it?

Either way, Kasdan noted, “it was only a matter of time before the issue of copyright infringement by AI apps was tested by the Courts.”

It remains to be seen how this case plays out, but one thing’s certain: whatever the outcome, the artists definitely have more to lose than the AI.

- Activision Blizzard Slapped With Another Sexual Harassment Lawsuit ›

- The Learning Perv: How I Learned to Stop Worrying and Love Lensa’s NSFW AI ›

- Is AI Making the Creative Class Obsolete? ›

- Art Created By Artificial Intelligence Can’t Be Copyrighted, US Agency Rules ›

- Is AI Art Real Art or Just a Gimmick to go Viral? - dot.LA ›

Samson Amore is a reporter for dot.LA. He holds a degree in journalism from Emerson College. Send tips or pitches to samsonamore@dot.la and find him on Twitter @Samsonamore.