This is the web version of dot.LA’s daily newsletter. Sign up to get the latest news on Southern California’s tech, startup and venture capital scene.

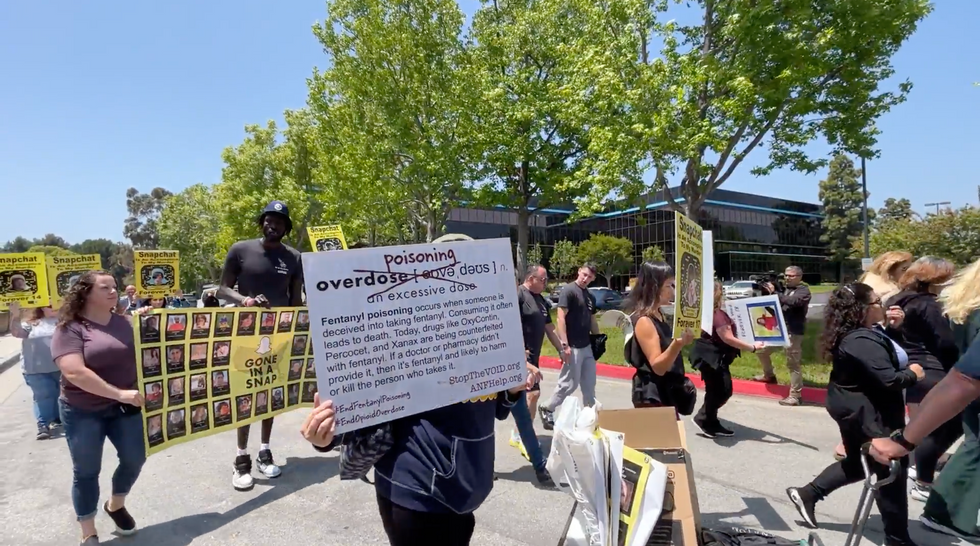

On a muggy Friday afternoon, over a dozen parents who have lost children to drug overdose or suicide marched to Snap Inc.’s Santa Monica headquarters to make their grievances against the social media company heard.

Numerous guardians took the mic and shared horrifying stories of finding their teenaged children dead in their own home after taking their own lives because of bullying on the app, or overdosing on illicit fentanyl obtained from drug dealers on Snapchat. The grieving parents carried bright yellow signs designed to look like Snapchat friend codes, with faces of their dead children in the center. Each poster displayed the date the child passed and noted they were “forever 17,” or the age when they died. They also had a slogan: “Snapchat is an accomplice to my murder.” The ages of the dead children ranged from 14 to 19 years old.

These protests have been happening for a while; dot.LA covered a similar march in June 2021.

Jeff Johnston, Sr., spoke about losing his son Jeffrey Johnston, Jr., to drugs he obtained via Snapchat. Johnston angrily took the mic and demanded CEO Evan Spiegel come out and face him. He also publicly encouraged Spiegel’s wife, Miranda Kerr, to divorce him, saying Spiegel was a “weak and evil man.”

Representatives from nonprofits including the Organization for Social Media Safety (OSMS) and ParentsTogether were also in attendance.

According to Snap spokesman Peter Boorgard, the company is working hard to stop dealers from abusing our platform. “We do this by employing certain technologies, working closely with law enforcement, collaborating with other technology companies, and by having a zero-tolerance policy where we shut off the infringer's account,” Boorgard said.

To his point, just last week, Snap announced it was a “founding partner” of National Fentanyl Awareness Day. And in 2021, Snap told Congress that banning drug sales on Snapchat is a “top priority.” But numerous parents told me that they feel Spiegel treats the problem of illicit drug sales on his app as “a PR problem,” and doesn’t view the situation as they do: A crisis.

As the modest group marched towards Snap’s inconspicuous headquarters at Donald Douglas Loop, I spoke with Amy Neville, the event organizer. She lost her son, 14 year-old Alexander Neville, in June 2020 to an overdose. Alexander unwittingly took fentanyl he thought was a pill of OxyContin or Xanax that he had received from a dealer that he’d connected with via the Snapchat app.

Legal relief

In attendance were Glenn Draper and Laura Marquez Garrett, attorneys for the Seattle-based Social Media Victims Law Center, who are representing the parents of Sammy Chapman who died at age 16 after he took Fentanyl he thought was Oxycodone. The Chapman family is working to pass Sammy’s Law, sponsored by Congresswoman Debbie Wasserman-Shultz of Florida, which would require social media companies to integrate third-party softwares that would allow parents to track their kids’ usage and interactions.

“If fentanyl is the bullet, Snapchat is the gun that's delivering the bullet to our children,” Samuel Chapman, Sammy Chapman’s father said.

Draper is working with both the Berkman and Chapman families along with roughly 65 others, and filed a lawsuit against Snap on January 3 in LA Superior Court. He's optimistic that once that case progresses to discovery, the public could learn a lot about how Snap’s algorithms work.

Draper also said that he thinks Section 230, which protects tech companies from the consequences of their users’ behavior, needs to change, and noted that Congress is moving to consider federal legislation to change the statute to hold tech companies accountable.

Parental controls

Last August Snap created a feature called Family Center, which allowed parents to see their teen’s friend list, and who they’re speaking with (if the child consents). But Neville and Marc Berkman, CEO of the OSMS, said that wasn’t enough.

Neville said that the Family Center “means that you have to create an account, [so] now they’ve got increased usership. You can see who your kid’s talking to, but not what they’re talking about,” she added. “They [Snap] equate that to, ‘you don’t listen to their private conversations.’ Maybe I do, maybe I don’t. But that option’s there, as a parent,” she said.

Disappearing content

One of Snapchat’s core features is the disappearing message. It’s been baked into the app since it launched in 2011, and it’s a key reason why people use the app. But the vanishing messages disturb parents who literally can’t see if their children are talking about drug sales, or being bullied. They’re asking for this data to be kept and accessible to users, a direct opposition to the app’s core function. The parents also allege the disappearing messages are why drug dealers prefer Snapchat to other platforms, since they can erase traces of their sales.

“This really isn’t a social media problem, this is a Snapchat-specific problem,” Draper said of the app’s unique functions. “You can use AI and all the most advanced moderation techniques to try and get drug dealers off of your site after the fact, but until you change the features that are attracting the drug dealers to your site in the first place, they're going to keep coming.”

Geolocation

Snap introduced a geolocation feature in 2017 called Snap Maps, which much like Apple’s FindMy app, lets Snapchat users see where their friends are. The feature was criticized almost immediately after launch, as parents raised concerns about it being perfect fodder for stalkers.

Users can turn this off, or choose to have only specific friends view their location. There’s also an option to go into “ghost mode,” which makes their location invisible. But parents argued that teens who might not know about these features’ settings and are liable to accept friend requests from strangers might misuse the feature. “They [dealers] use geolocation to find children in areas where they might be able to pay for the drugs, they solicit those children and then they use Snapchat to connect the dealer with the child and to make the arrangements for the drug deal,” Berkman argued.

Third-party monitoring

Neville and other parents also said they want neutral parties to be tasked with monitoring the company’s progress. “As far as our government and legislation are concerned, I really want that duty of care followed by third party auditing, because at this point, so much crime has happened on their platform,” Neville said. “We’re just supposed to take their word for it nowadays, we need third party auditing.”

These third parties, Neville suggested, could be law enforcement, the Organization for Social Media Safety, or anyone “who really can take a hard look at it and don't have any financial ties.”

Back in 2021, Snapchat said it was “generally open” to using third-party software, but Spiegel’s also said that it might not work, citing user privacy and scalability issues.

“We would take that on so long as we were completely independent of Snap,” Berkman said of being a Snapchat auditor. “The arrangement would have to enable complete independence and the funding for that process would have to be independent of a specific platform or the [tech] industry general.”

Editor's Note: Snap Inc. is an investor in dot.LA.

- Snapchat’s New Wildlife Crossing AR Experience Hopes To Keep Mountain Lions — and Itself — From Going Extinct ›

- TikTok Will Tell You To Take a Break With New Screen Time Tools ›

- Why Children’s Advocates Say Social Media Apps Are Like Casinos ›

- Why Schools Across the Country Are Suing Social Media Companies ›

- How 'Ginormo' Plans to Make Youtube Videos Cinematic - dot.LA ›

- Google Alters Search Results, Snapchat’s AI Girlfriend - dot.LA ›