Graphene Stands to Revolutionize Audio, but First It Has to Get Past Industry Inertia

Sam primarily covers entertainment and media for dot.LA. Previously he was Marjorie Deane Fellow at The Economist, where he wrote for the business and finance sections of the print edition. He has also worked at the XPRIZE Foundation, U.S. Government Accountability Office, KCRW, and MLB Advanced Media (now Disney Streaming Services). He holds an MBA from UCLA Anderson, an MPP from UCLA Luskin and a BA in History from University of Michigan. Email him at samblake@dot.LA and find him on Twitter @hisamblake

When you put on headphones or listen to loudspeakers today, you are likely tapping into the same underlying technology that was invented in the late 19th century to convert electrical energy into sound.

That's not to say that audio technology isn't slimmer and sleeker, but there hasn't been nearly as much innovation as in video. That's at least the view of GraphAudio, a four-year old startup whose product is based on Nobel Prize-winning technology, which it hopes will bring about the next frontier in audio.

"We want to bring an audiophile experience to the mass market," said chief executive Ramesh Ramchandani, "and become the 'Intel Inside' of audio."

The headphones market has nearly doubled over the past two years. In 2019, Apple's Airpods yielded more revenue alone than Twitter, Snapchat and Spotify combined.

The Beverly Hills-based company is hoping to penetrate that market and capture a sizable chunk with tech that enables a superbly crisp listening experience, made from a miraculously efficient and effective material, which can ultimately be offered to end-consumers at a competitive price.

For 30 years, Ramchandani has worked in tech, primarily in semiconductors, first as a design engineer and later as head of several startups with successful exits. Along the way, he helped GoogleX set up its artificial intelligence strategy.

Two years ago, GraphAudio cofounders Fred Goldring, an L.A.-based entrepreneur, and materials scientist Lonnie Wilson, who'd previously worked out of the California Nanosystems Institute at UCLA, recruited him to lead the company.

What convinced Ramchandani to saddle up was the opportunity to mass-market a new technology that vastly improves sound and could be used in everything from smartphones to televisions.

The company has perpetual, exclusive licenses to several patents developed out of the Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory for audio components made from graphene, and $4 million in seed funding from investors including will.i.am and Herbie Hancock.

But so far GraphAudio can produce only a few hundred units per month of its technology out of its lab in Austin. That's because its process to manufacture at scale, which uses a technique called chemical vapor deposition, requires a more robust facility, and the company has yet to sign on a big-name customer. It also needs to shrink its brick-sized prototype amplifier, which provides the extra voltage needed by its electrostatic speaker system, to the size of a microchip.

Ramchandani thinks the company can smoothly overcome these engineering challenges and enable its technology components to fit into the headphones, televisions and smartphones of the customers GraphAudio is targeting. And he's chasing that vision so that he can bring to a mass market what he sees as the gold standard of audio, at or below prices that consumers already pay. But what he really needs to do is sell his technology to the companies that make those products.

GraphAudio's Challenges Ahead

Ramchandani said he is in "active discussions" with at least two companies, though would not say which ones specifically, citing non-disclosure agreements. But he said the companies were equivalent in size and stature to players such as Sony, Sennheiser, Samsung or Bose.

Jim Rondinelli, an audio expert and chief operating officer of audio-tech company Immersion Networks, sees a compelling case for GraphAudio to make to its target customers.

For an ideal loudspeaker or headphone, he said, "there's no better material than graphene."

For example, whereas Apple's earbuds convert only about 8% of their power source into sound, GraphAudio's transducer converts 99%. That's according to Alex Zettl, a physicist whose work formed the basis of the company's technology and who now sits on its advisory board. Those efficiency gains have several knock-on effects, such as improving battery life and reducing the amount of heat that gets dissipated across devices, which can damage other components.

But companies like Apple that are already succeeding in the audio market may be disinclined to change what they are doing. Rondinelli said, for instance, that Apple may have "some resistance to change because they already carry a lot of power and negotiating leverage."

Other companies prefer to stick to technologies they develop. A representative from Sennheiser, a German audio hardware company, said it continuously evaluates new technologies to improve listener experience. "However, as an audio specialist with a 75-year heritage, we utilize proprietary transducers for the majority of our headphones."

Is Graphene the Next Big Thing in Audio?

The key to delivering any sound to a listener's ear through speakers or headphones is a transducer: the basic technology that converts electrical energy into sound. It makes beats thump and voices soar.

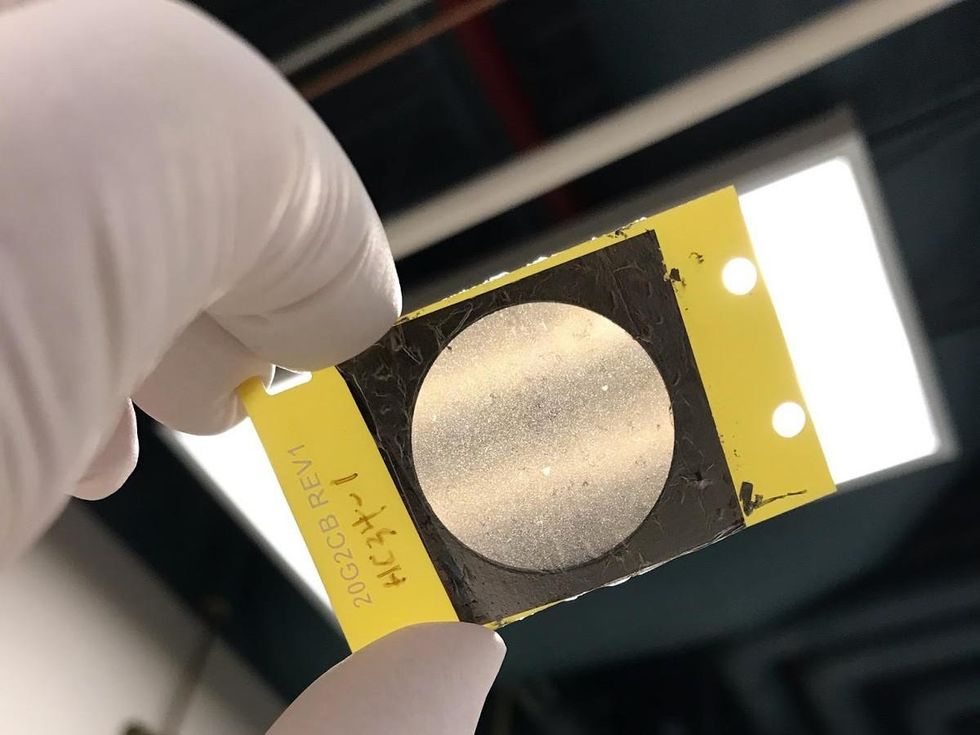

In 2016, GraphAudio acquired an exclusive license from the University of California, Berkeley's Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory to monetize patents that describe a transducer made out of graphene: an ultra-lightweight, stronger-than-diamonds carbon-based material that in its purest form is the only two-dimensional material on Earth.

Those patents were filed on the heels of a landmark paper written by UC-Berkeley physicists Zettl and Qin Zhou, which highlighted graphene's unique usefulness as a transducer for an electrostatic speaker.

Wilson, who would go on to co-found GraphAudio and is now its chief technology officer, had long been interested in graphene by the time that paper was published. The remarkable material had existed mainly as an intriguing theoretical concept until Andre Geim and Konstantin Novoselov won a Nobel Prize for their experimental work on graphene in 2010.

"I was looking for the next big thing and I really thought graphene, although it had been out there and they'd been trying to find a good application for it, was looking for a good home," Wilson said. "What really caught my eye was this graphene work that Zettl was working on up at Berkeley."

Competition for Graphene Speakers

GraphAudio's biggest competitor so far is Montreal-based ORA Graphene Audio. The company develops graphene-based speaker and headphone components, and has earned some revenue through joint-development partnerships with brands it describes as "well known."

ORA has sold headphones directly to consumers through a Kickstarter campaign, but ran into some production delays along the way. It is now only pursuing a B2B strategy, like GraphAudio.

The two companies' products are not identical. GraphAudio uses stacked layers of 100% pure graphene. By contrast, ORA's "graphene oxide" includes oxygen, in addition to what co-founder Ari Pinkas called a "magic formula" of materials that enable ORA to mold its components into a variety of shapes depending on its customers' needs.

That difference matters, Pinkas said, because at this point graphene oxide is easier to produce at high volumes. Novoselov, the Nobel Prize winner, has praised the company for offering "one of the first consumer products to feature a high-content graphene technology."

Another key difference between ORA and GraphAudio is that ORA does not rely on an electrostatic speaker design but rather the more common electrodynamic coil (see below section). Pinkas said this has helped his company forge partnerships with brands that are testing the product.

GraphAudio's transducer, however, can dual-function as a highly sensitive microphone – for which the company also holds a patent. That could help Ramchandani's sales pitch, as reducing the number of parts in a consumer device by combining a speaker and microphone would open up valuable real estate on those devices.

This microphone capability is key to GraphAudio's longer-term plans. Since it can detect frequencies beyond the normal range of human perception – it has registered ultrasonic wild bat calls, for instance – it holds potential for applications well beyond consumer audio. Wilson noted that autonomous cars could use it to communicate with each other, and that it could also be used for medical and military purposes, among others.

So, while Ramchandani, Wilson and team have a product with plenty of promise, there's still a long road ahead.

"We're on the 1-yard line in terms of our development cycle," Ramchandani said.

Still, he expects his company will advance down the field rather quickly, predicting that products with GraphAudio inside will be available to consumers by 2022. A big payout could await.

"We recognize we have challenges," Goldring said, "but we see ourselves disrupting audio in much the same way flatscreens revolutionized video."

If GraphAudio overcomes its hurdles, Rondinelli concurs. "It's easy to imagine a scenario where these guys are shipping hundreds of millions of devices," he said.

How an Electrostatic Speaker Works

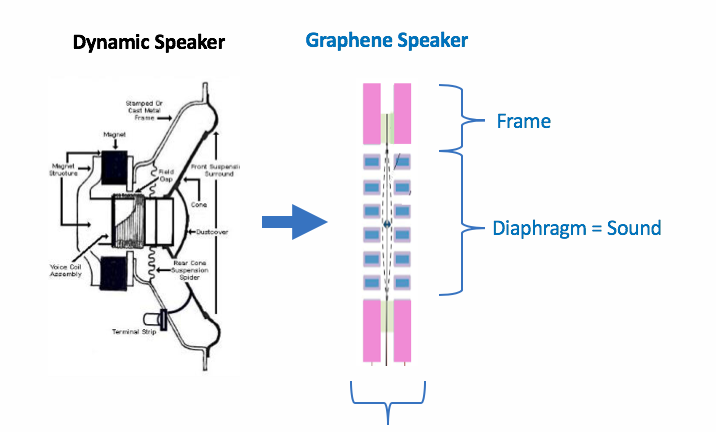

The most popular way to transduce electricity into sound has long been the dynamic coil speaker. It works by using a coil of wire and a magnetic current to nudge a magnet that physically pushes air through an open chamber, usually shaped like a cone; this creates vibrations that ultimately move the tiny hairs inside our ears, which our brains perceive as sound.

Electrostatic speakers work differently. Rather than using a transducer that relies on a magnetic field, coil and chamber to propel sound waves, they use an electric field to vibrate a round, flat and super-thin membrane which emits the pressure waves that we hear as sound.

Though still relatively rare, their development accelerated with World War II-era materials advances. Today the super-thin membrane is most commonly made from mylar, a type of plastic. MartinLogan sells electrostatic loudspeakers and Stax has a headphone version.

The speakers are typically more efficient at converting electrical energy into high-quality sound and tend to be more resistant to the deterioration that causes sound distortion.

But bass notes aren't traditionally as rich on electrostatic speakers, and they require relatively high levels of power. That usually means users must also buy an external amplifier, making them more expensive. GraphAudio believes that by replacing mylar with graphene, however, and pairing it with an amplifier that fits inside consumer hardware, it can overcome the shortcomings of electrostatics and make them ubiquitous, while improving battery life and even speeding up manufacturing.

---

Sam Blake primarily covers media and entertainment for dot.LA. Find him on Twitter @hisamblake and email him at samblake@dot.LA

Sam primarily covers entertainment and media for dot.LA. Previously he was Marjorie Deane Fellow at The Economist, where he wrote for the business and finance sections of the print edition. He has also worked at the XPRIZE Foundation, U.S. Government Accountability Office, KCRW, and MLB Advanced Media (now Disney Streaming Services). He holds an MBA from UCLA Anderson, an MPP from UCLA Luskin and a BA in History from University of Michigan. Email him at samblake@dot.LA and find him on Twitter @hisamblake

Image Source: Skyryse

Image Source: Skyryse

Image Source: Northwood Space

Image Source: Northwood Space