'We're in the Business of Creating Music': Can a New App Make Meditation as Easy as Listening?

Sam primarily covers entertainment and media for dot.LA. Previously he was Marjorie Deane Fellow at The Economist, where he wrote for the business and finance sections of the print edition. He has also worked at the XPRIZE Foundation, U.S. Government Accountability Office, KCRW, and MLB Advanced Media (now Disney Streaming Services). He holds an MBA from UCLA Anderson, an MPP from UCLA Luskin and a BA in History from University of Michigan. Email him at samblake@dot.LA and find him on Twitter @hisamblake

Neal Sarin experienced some great results from meditating – better sleep, more creativity and sharper intuition, he said – but he realized not everyone has the time or resources he invested to learn the practice.

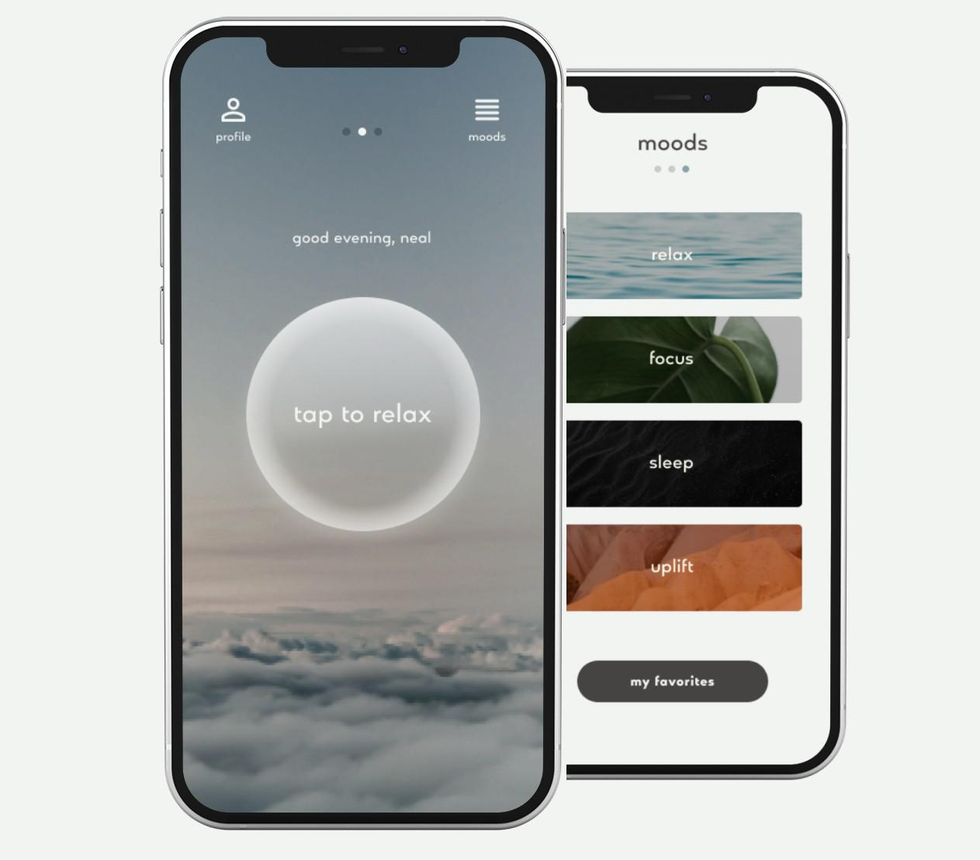

Now Sarin, a former A&R director at South Asian music streaming company Jio Saavn, is aiming to use music to bring meditation to the masses with Sona, his new app that launches today.

"As a society we've been conditioned to view music as a means of entertainment, when really music is healing and medicinal," Sarin said.

Sarin formed his company in 2019 and has worked with eight composers across the world to build an exclusive library of songs meant to help users tap into brain states that mirror the effects of meditation.

Plenty of other apps aim to do similar things. Headspace and Calm guide users through meditation practice to bring them more mindfulness and less stress. And there's no shortage of playlists on Spotify or YouTube purporting to help listeners "chill" or "focus."

But Sarin said a few factors make Sona different.

One is a proprietary composition process for the app's music. Sarin, who is also a musician, described this process as a set of eight or nine elements that are conducive to helping listeners achieve a meditative brain state. These include a slow tempo and frequent repetition of musical phrases. But it's important to him that these guidelines don't overly restrict his composers' creativity.

"We're never going to be in the business of licensing a bunch of rain sounds or sine waves that apparently are stress-reducing. We're in the business of creating music," Sarin said.

Sona pays composers on a per-song basis and retains 100% of the master copyright and 50% of the publishing rights, he said. The current stable of eight composers are spread as far as London and Tel Aviv, in addition to New York and L.A.

"Something that I say to composers when we're working with them is that we've got to think about making ambient pop songs," Sarin said.

Another differentiator, he noted, is Sona's focus on science.

"We don't want to just say that our music has therapeutic benefits and meditative benefits," Sarin said. "We actually want to validate it."

In 2020 Sona tested the effects of its music through a study it commissioned with the neuroscience division of market research firm Nielsen, which subsequently sold that subsidiary, now called NielsenIQ.

Working with 64 participants, all non-meditators and split by gender, the study used an EEG to monitor electrical activity in their brains. Half listened to Sona songs for 10 minutes, and half listened to traditional easy listening tunes, á la John Mayer.

"Participants demonstrated greater memory and attention during Sona music and less attentional focus and more relaxation after the music," NielsenIQ's head of science and research Avgusta Shestyuk wrote in an email.

Her group used a proprietary method that looks at so-called theta, gamma and alpha brainwaves to measure these outcomes, she added. The results have not been peer reviewed, but Sarin said the research plan was approved by an independent review board.

In the future, Sarin wants to study the long-term effects of Sona's music as well, such as whether ongoing use leads to improved sleep or reduced stress over a sustained period of time.

"We take research very seriously and moving forward we'll be conducting a lot more," he said.

The company has recruited several scientific advisors, including UC Berkeley neuroscientist Robert Knight and the president of the Sleep Research Society of America.

When Sarin was at Jio Saavn, he mostly worked with pop and hip-hop artists, including Nas and Marshmello. But he was struck by the gap between what he viewed as a broad demand for the benefits of restorative music and the low investment that companies make in it.

"Why aren't we signing [restorative] composers and developing them the same way we do hip-hop and pop artists?" he remembers thinking.

Sarin bootstrapped his company, though he said he is in active conversations with investors.

The app will run on a freemium model, with a limited version available for free; those users will be able to listen to songs that fall under Sona's "relax" category. For $3.99 a month or $29.99 a year, premium users will have access to Sona's full library of songs, including those classified under "sleep," "focus" and "uplift", in addition to extra features like reminders, timers and favoriting.

Sona may also eventually license its music. But adding advertising is unlikely.

"I think that would deter from the whole purpose of the application itself," Sarin said.

Sam primarily covers entertainment and media for dot.LA. Previously he was Marjorie Deane Fellow at The Economist, where he wrote for the business and finance sections of the print edition. He has also worked at the XPRIZE Foundation, U.S. Government Accountability Office, KCRW, and MLB Advanced Media (now Disney Streaming Services). He holds an MBA from UCLA Anderson, an MPP from UCLA Luskin and a BA in History from University of Michigan. Email him at samblake@dot.LA and find him on Twitter @hisamblake

Image Source: JetZero

Image Source: JetZero