With Sky-High Stakes, What Can Studios Do to Fight Piracy?

Sam primarily covers entertainment and media for dot.LA. Previously he was Marjorie Deane Fellow at The Economist, where he wrote for the business and finance sections of the print edition. He has also worked at the XPRIZE Foundation, U.S. Government Accountability Office, KCRW, and MLB Advanced Media (now Disney Streaming Services). He holds an MBA from UCLA Anderson, an MPP from UCLA Luskin and a BA in History from University of Michigan. Email him at samblake@dot.LA and find him on Twitter @hisamblake

The entertainment industry is navigating choppy waters in a sea of uncertainty that is evidently filled with pirates.

Content pipelines have been crimped due to shooting moratoria and the suspension of live events. Advertising revenues are plummeting. Although streaming consumption is up, many viewers will soon face tough choices about how to spend their money amid an economic downturn. Competition continues to grow. And ongoing health concerns stemming from the coronavirus may put an irreversible dent in businesses that require congregating in close quarters, like movie theaters and theme parks. Speculation of consolidation and bankruptcy is bubbling.

Given such headwinds, anti-piracy has arguably never been more important. Protecting revenues has taken on more urgency in these turbulent times.

Yet new analyses suggest that anti-piracy measures are failing. Muso, a British anti-piracy firm, recently found that film piracy in the U.S. was up an "unprecedented" 41% in the final week of March compared to the final week of February.

Reports have suggested that all the unreleased episodes of The Last Dance, a Netflix-ESPN collaboration about the Michael Jordan-era Chicago Bulls that has been a lifeline to starved sports fans, are available for unsanctioned viewing.

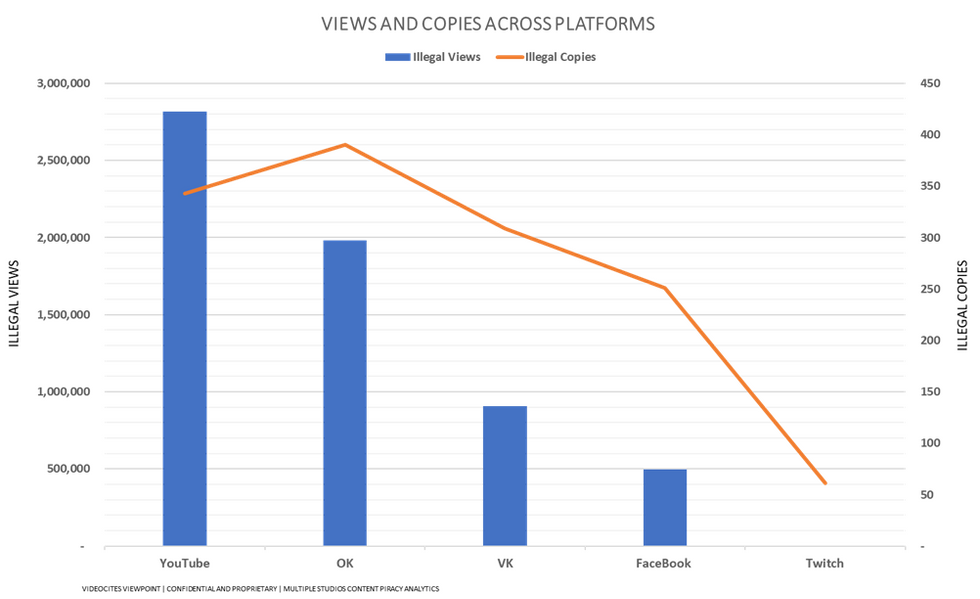

And an analysis exclusively shared this week with dot.LA found that four major studios lost $100 million in 23 days due to pirating across six major releases made available on streaming platforms from March 20 - April 11. The finding comes from Videocites, a video analytics firm founded in 2014 with offices in Israel and Beverly Hills. Videocites did not wish to disclose specific titles or studios.

In 2019, the U.S. Chamber of Commerce found that TV and film piracy costs the industry up to $71 billion annually. When sports are included, that number climbs to nearly $230 billion.

While determining an exact dollar figure is ripe for miscalculation because of the uncertainty over whether pirate consumers would have otherwise bought the title legally, three things about piracy are clear, said Mike Smith, professor of marketing at Carnegie Mellon and co-author of a report on digital piracy recently presented to the U.S. Patent & Trade Office.

One is that piracy hurts sales. For some time the question was unclear, since theoretically piracy can provide promotional benefits. But after 29 out of 33 peer-reviewed articles reached the same conclusion, "it's not an interesting debate anymore," Smith told dot.LA.

Also true, though not quite as well documented in the literature, is that digital piracy reduces investment in creative content -- and therefore the volume of creative output.

"If I were a studio executive," Smith said, "I'd be worried that people are getting comfortable with piracy right now."

Whack-a-mole?

It is often said that fighting piracy is like a game of whack-a-mole, explained James Maysonet, head of business development at Videocites and author of their new paper. In other words, there will always be new ways for pirates to circumvent content protections.

A globalized marketplace doesn't make deterrence any easier, noted Smith, since not all countries protect copyright equally.

Further complicating matters is the sheer variety of reasons why pirates post illegal content, Muso Chief Executive Andy Chatterley told dot.LA. "The whack-a-mole analogy doesn't give justice to the actual reality," he said. "It's more complex." A pirate's motives may be financial, malicious, fame-seeking or otherwise.

Smith also disagrees with the analogy: "The argument makes perfect sense, except it's wrong. Because it doesn't take into account the fact that people are lazy."

What to do?

The final thing the academic literature makes clear, Smith says, is that pirate consumers are just like regular consumers in one essential way: they respond to incentives.

"Making it harder to consume pirated content reduces illegal consumption, and increases legal consumption," Smith said. He emphasized that it isn't necessary to remove every single nefarious on-ramp to illicit content. For example, when the British government blocked access to The Pirate Bay, a popular piracy site, there was little change in pirated consumption. "But when they blocked the next 18 and then the next 53 most popular sites, that's when you saw increases in legal streaming consumption. You don't have to make it impossible."

Indeed, Maysonet claims that 90% of illegal streaming is done in broad daylight, on social media sites like Facebook and YouTube. This, he proposes, suggests that relatively modest increases in piracy protection could make a big difference.

"We're not talking about the sinister dark web that requires a person to download Tor, buy a VPN, and navigate the backwaters of internet hell," Maysonet wrote in his Videocites paper.

One solution he touts is his own company, which uses video-based artificial intelligence to create a "fingerprint" for visual assets, then scan the internet intermittently to identify and flag illegal copies.

Muso offers a similar service, except according to Chatterley it focuses more on an asset's metadata. Maysonet, speaking generally about anti-piracy methods, claims a metadata approach has lower capability than fingerprinting to find pirated assets, employing as they do disguise tactics like removing or obscuring metadata, flipping the video feed upside-down, chopping it up into tiny segments, or obscuring an asset's watermark. Chatterley says the advantage of a metadata approach is its cost and speed.

As for legal recourse, a content-protection battle is currently underway in the European Union. According to Maysonet, the key issue is whether digital platforms should be held liable for displaying pirated content. In March, the U.S. Senate's Intellectual Property subcommittee held a hearing to examine how other countries handle digital piracy, with particular attention paid to this EU Article 17 debate.

Maysonet said that U.S. companies are closely watching the proceedings. Whatever happens, he believes studios should invest more in IP protection. And he thinks Guilds ought to demand it to protect the financial interests of their members.

From Control to Convenience

But for the major studios, Smith wonders if the writing is already on the wall.

"I think the studios should be much more worried about Netflix's business model than they are," he said, echoing the thesis in a 2019 piece he co-wrote for Harvard Business Review.

Never mind that Netflix, which blew earnings expectations away last week, isn't vulnerable to today's advertising squeeze. Nor that, unlike many of its competitors, it isn't tied to other business units that have been hammered by the coronavirus fallout. What really sets Netflix apart, says Smith, is that its business model is based on convenience rather than control.

"For (the studio) business model to work, you've got to be able to control when people get access to the content," he explained. Piracy undermines that control.

"I think we're seeing a transition from a control-based business model to a convenience-based business model," Smith concluded. "You see that with Disney+, HBO Max, NBC Peacock, and the others."

Maysonet doesn't entirely agree that the theatrical model is done. Nor does he think it makes much difference.

"If we continue with the status quo," he wrote, "the pirates will continue to damage our industry."

---

Sam Blake covers media and entertainment for dot.LA. Find him on Twitter @hisamblake and email him at samblake@dot.LA

- Streaming Piracy Is Now a Billion-Dollar Industry - dot.LA ›

- Streaming Piracy Is Now a Billion-Dollar Industry - dot.LA ›

- The EU's Article 17 Is Already Changing Digital Music Deals - dot.LA ›

- LA's Movie Production Continues to Fall as COVID Surges - dot.LA ›

- Who Will Biden Pick to Run the US Patent Office? - dot.LA ›

- Imgur's Plans to Get Rid of All NSFW Content - dot.LA ›

Sam primarily covers entertainment and media for dot.LA. Previously he was Marjorie Deane Fellow at The Economist, where he wrote for the business and finance sections of the print edition. He has also worked at the XPRIZE Foundation, U.S. Government Accountability Office, KCRW, and MLB Advanced Media (now Disney Streaming Services). He holds an MBA from UCLA Anderson, an MPP from UCLA Luskin and a BA in History from University of Michigan. Email him at samblake@dot.LA and find him on Twitter @hisamblake

Image Source: Revel

Image Source: Revel