This App Hopes to Give Homeless Outreach Workers Real-Time Data While They're on the Street

Los Angeles invests hundreds of millions each year to alleviate homelessness, but the networks that underlie those efforts are often held together by legal pads and spreadsheets.

It took a person who's suffered through the system to try to update it, so that the homeless and their advocates can get what they need, when they need it.

Anthony Greco is one of the few people who can say he's been on most sides of the issue. He's lived on the streets, dealt with homeless family members and friends, he's worked in the shelters and counseled people dealing with substance abuse.

"I've literally been on every side of this problem in one way or another," Greco says. "I've been trying to get people into treatment in some way or another since I was seven years old."

The Get Help platform is a result of his lifetime of experience with substance abuse and homelessness. And it's been so effective that Los Angeles took it from beta to a basic tool in the city's plan to deal with one of its largest emergencies: Getting homeless people off the street during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Anthony Greco is the founder of the Get Help app.

A Lifetime Getting People Help

Greco grew up bouncing from house to house while his mother sought help at substance abuse clinics.

"When I was 15 years old, one day I came home from school and my mom and her boyfriend and that family had moved away out of town," Greco says, "and the house was empty except for all the stuff in my room."

That led him into his own struggle first with homelessness, then with substance abuse and finally into recovery and toward helping people in the same circumstances he'd once found himself in. Ultimately, he got his PhD in clinical psychology and worked with patients with substance abuse issues.

But at every step in his career, Greco found himself trying to solve the same problem: How do you match a person to the services they need at the moment they're willing to ask for help? Having real-time information is key, he says.

"There's a point when someone says that they want to get help," he says. "It's a simultaneous feeling of excitement and absolute dread at the same time, because on one hand, you're so excited that they want to get help and they want to go somewhere and then on the other hand the next thought is where am I going to go? Where am I going to call with how am I going to find an available bed? And it's a nightmare."

Once someone is willing to get help, the next question is where, and how? Greco describes calling rehab and shelter facilities as a child, as a homeless man and as a clinical psychologist to find a client or friend a bed, only to find that facilities were full or not accepting new residents, or that no one at the center seemed to have an idea of whether they had a place to stay.

Later, he encountered the same problem from the other end of the phone line when he was working at those same facilities.

"I remember getting calls, late at night," Greco says. "It was a mom on the other end of the phone wanting to know whether I have space for their son or daughter. And I didn't even know what our census was."

Had he known the headcount, he would have known how many available beds there were.

If Getting Shelter Were As Easy As Ordering an Uber

The idea for the app came when Greco, now a psychologist, found himself unable to get the same basic information he was seeking as a kid.

"I realized that it was just as difficult for a licensed clinical psychologist to get someone into treatment as it was for a seven year old."

Greco had pictured a simple app that would match the world of homeless needs to the world of resources available to them.

"I said, you know, there has to be an app for that," he says. "You can order a pizza at four o'clock in the morning, or a cheeseburger from Sonic and have it delivered from Pomona, but there's no tool to be able to find a bed for my friend."

Greco quickly realized that if he wanted to be able to offer immediate help, he needed more than a list of numbers; he needed accurate real-time data. Who had open beds right now, tailored to specific needs of individuals — with substance abuse problems, with mental health problems, with kids, with domestic abuse trauma, with medical needs?

He had a vision for the app, but he didn't have a background in tech or business. Luckily, as he searched for funding for the idea, he came across Michael Root, one of the early engineering pioneers at Riot Games, who quickly volunteered to be Get Help's CTO. The company registered as a public benefit corporation in 2019.

"I had no idea what I was getting into," Greco says.

Solving Problems for Homeless People

Greco says it usually takes between 6 and 7 approaches (sometimes more) before someone who's experiencing homelessness will accept help — and often the kind of help people on the street are looking for isn't what street teams have to offer.

"The first service that they often will accept isn't a bed," says Greco, "but they'll accept a place where they can go get a meal."

Greco says it's critical to seize those moments, where a person is willing to ask for some kind of help, if only to build trust.

"It's about meeting the person where they're at," Greco says. "And that's what I do as a therapist."

In other words, he says focus on building trust, and provide people what they need, rather than what you think they need. Not everyone is looking for a shelter bed.

"That's where I operate from and where Get Help operates from," he says.

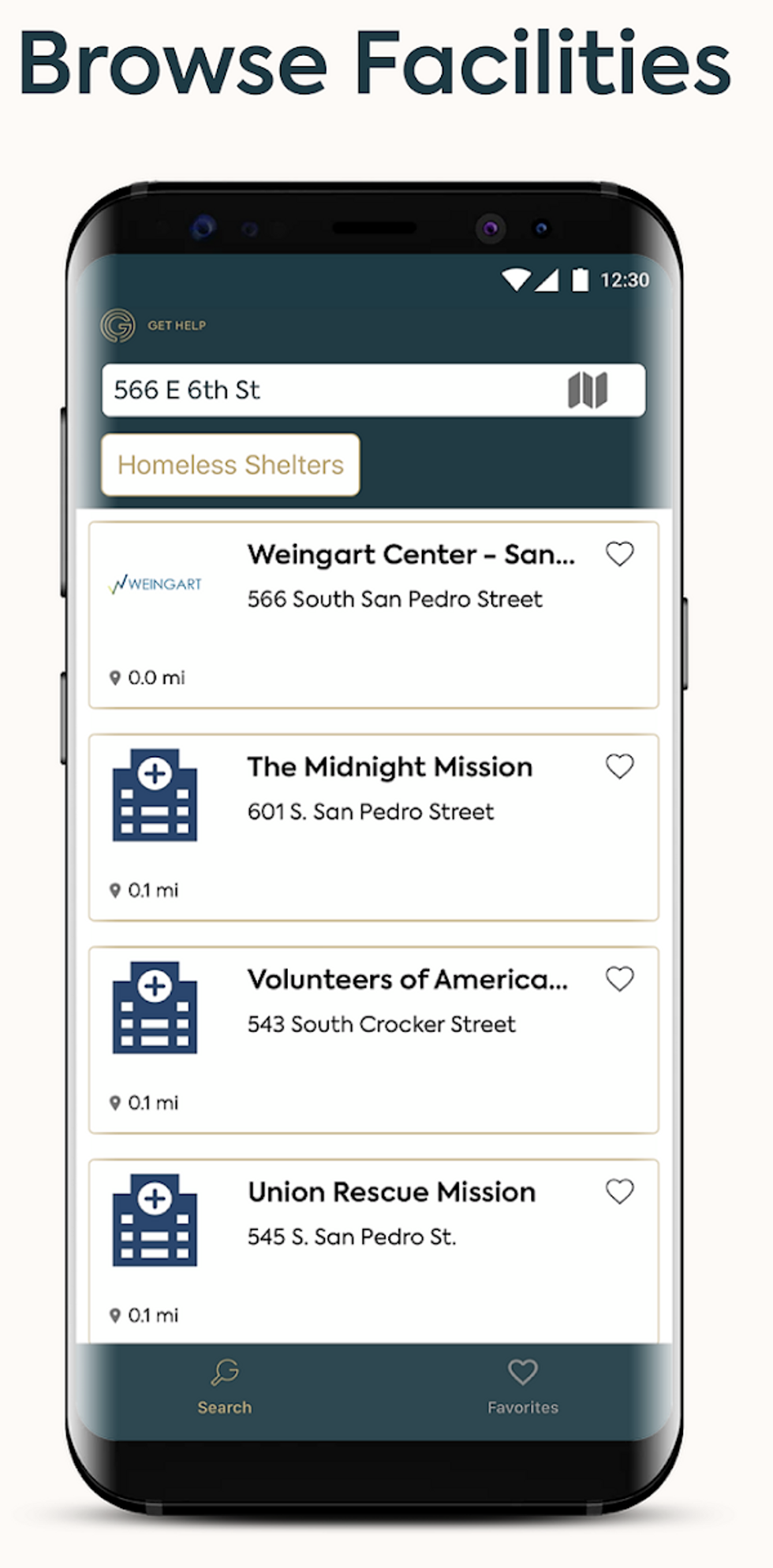

The app tries to reflect this by listing a range of services both big and small from shelter and sober living beds to food pantries, showers, laundry, storage facilities and health care services. All those services are what social workers call a continuum of care that will eventually lead to stability, he says.

Solving the Problem for Shelters

On the other end of the spectrum, Greco realized that if he wanted to be able to solve family members' 4 a.m. emergencies, he'd have to work with the shelters to get the data that would be crucial to getting their loved ones fast help.

What he quickly found was that many of these shelters and sober living facilities were using outdated tools to keep track of who was in their facility.

"They were still managing their inventory — and still are — is literally using yellow pads, sometimes whiteboards, Excel documents and email exchanges."

They reached out to the Weingart Center, one of the first shelters in Skid Row that specializes in providing emergency housing for people with mental illness. By the estimate of its current CEO, the company houses about 600 people nightly, and provides counseling, employment and other other services to thousands more. All of that requires an incredible amount of record keeping.

"In order to really run an operation," says Weingart's CEO, Kevin Murray, "you've got to do intake, you've got to assign room, you've got to assign food cards."

In addition, you have to make sure you're collecting the information that health insurers and the federal government require, as well as making sure you're tracking the basic needs — linen and toothbrushes, for example — of the people you're serving.

"Almost every provider is inputting this practice information in, you know, at least two, maybe multiple systems."

Greco's team met with Weingart to develop a data management system that could help them track that information.

"They actually sat down with our people at all levels to find out what they needed, and what would be helpful to them," Murray says. "We both sort of opened up to each other about what we wanted to do. And so we were participants in developing the system."

The result, Greco says, saved Weingart time and money by cutting down the number of steps that shelter staff had to take to do intake and reducing the number of data entry mistakes they made.

"Those errors result in billing errors," and those billing errors and mistakes can result in a place like The Weingart Center losing millions a year in funding opportunities.

It also made the information on how many beds the center had at any given time easily accessible, so that Get Help's app could make them available to service providers on the streets looking to get people housed.

"it's certainly, you know, added a lot of simplicity in our lives," Murray says.

From Pilot Test to a Citywide Crisis

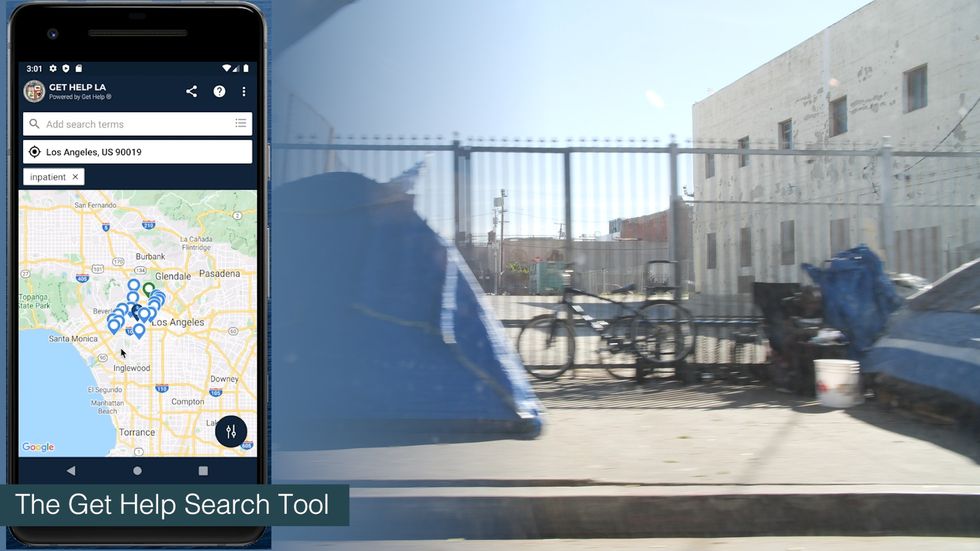

In late 2019, Get Help worked out a pilot program with a small faction of LAPD officers who patrol Skid Row and other areas to assist with routine clean ups of homeless encampments.

The officers in LAPD's Homeless Outreach and Proactive Engagement (HOPE) team downloaded the Get Help app and used it to direct the homeless folks they encountered to services in the area.

"The response was overwhelmingly positive," Greco says, adding that some officers reported it had changed the dynamic between some of their patrol and homeless in the area. Officers had real-time information they could offer to homeless folks, and their role went beyond enforcement to being able to offer assistance.

After six months, the plan was to expand the app's use in the city, when an even larger crisis hit.

"We had just got through a successful pilot with L.A. (city) and we're talking about expanding it, we were doing work on expanding to a different additional shelters, (and) we were starting conversations with L.A. County," Greco says, "And COVID-19 hit."

The city settled on an emergency plan to house vulnerable homeless people in recreation centers and other city facilities that had closed due to the pandemic.

Jimmy Kim oversees emergency operations for Los Angeles's recreation and parks department. He was tasked with creating the shelters, developing a system for keeping track of its inhabitants, and keeping them safe.

"The systems that we're using are so archaic," Kim says. "You know that saying, 'time is money', right?"

At first the city relied on regular manual headcounts, pen and paper and Google docs to keep a tally of those staying at its sites. It quickly found that process was inefficient.

"And so we came across (the app) in the mayor's office," says Kim. "They actually introduced us to the folks over at Get Help as part of a pilot program."

The app allowed them to streamline the process, and provided the mayor's office with real time information on the number and location of beds occupied.

"The quicker we could get them (registered), the quicker we could get people in," Kim says. "And then the less time they have to spend on doing registration, the more time they could spend on doing more important things."

The system proved a success, allowing Kim to keep track of registrations and discharges at the 24 shelters the agency oversaw, and allowing his staff of around 94 employees access to real-time data on who was where.

"I actually want to take that and use it for our normal shelters as well because it'll help us streamline that process and get real time usable data," Kim says. "You know, literally at the tip of your fingertips."

The department is now thinking about configuring the app to do contract tracing for shelter residents who come down with COVID-19, and it's thinking about expanding beyond the homeless emergency function, to other emergencies that require rapid sheltering — such as wildfires and earthquakes.

"Now, we're having those conversations," says Kim, "because I think it will help us streamline and get data a lot quicker… And if you have real-time data, you can make better decisions that way."

Meanwhile, Get Help is available to individuals, organizations and outreach workers in Apple's App Store and Google Play. His team is working with several large local shelters and sober living facilities and the county to expand the data available in Get Help's app that can be used by families, street teams and concerned residents looking for immediate help.

- Investing in Tech and a Vision to Strengthen LA's Social Net - dot.LA ›

- How to Turn On California's COVID-19 Contract Tracing App - dot.LA ›

- Samaritan App Builds a Support Network for LA's Homeless - dot.LA ›

- Our Community LA Creates App to Help Homeless Find Services - dot.LA ›

Image Source: Tinder

Image Source: Tinder Image Source: Apple

Image Source: Apple