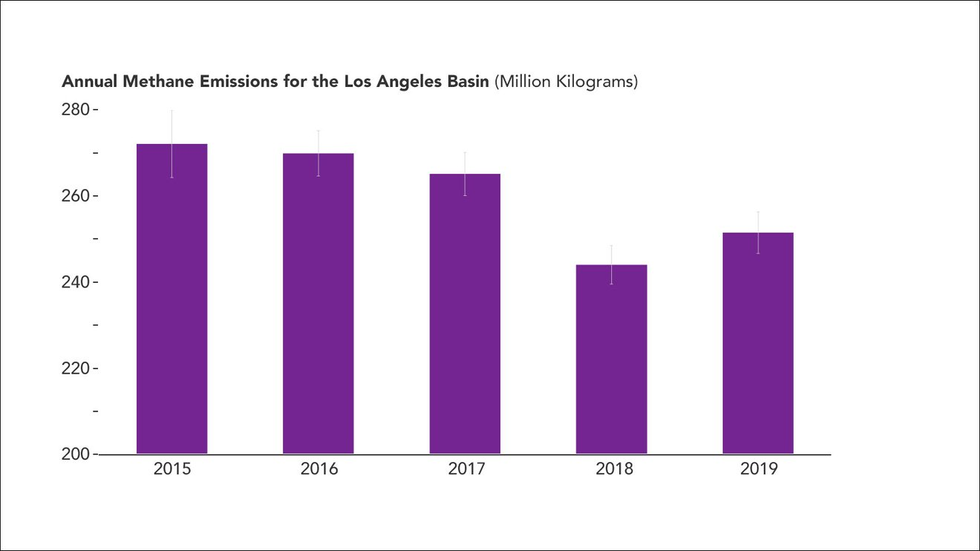

Multiple studies conducted by NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Pasadena using both airborne and ground-based sensors have found that the overall rate of methane gas emissions in Southern California have fallen in recent years.

From 2015 to 2020, one NASA study found that the LA Basin’s annual emissions fell by about 7%. Put another way, there were 33 million fewer pounds of methane released into the atmosphere during that time.

That study was authored by JPL data scientist Vineet Yadav, who told dot.LA, “if you have to make an immediate impact [on climate change], then the reduction of methane is very important.” In a report published this February, the JPL and California Institute of Technology found that the Los Angeles Basin (which spans the LA, Orange, Riverside and San Bernardino counties) was responsible for around 20% of all of California’s methane emissions.

The California Department of Energy lists 16 active oil refineries in the state, and several – including Chevron’s El Segundo plant, Marathon Petroleum’s Carson refinery and PBF Energy’s Torrance facility – are within LA County. At their peak, these refineries pump out over 360,000 barrels of oil per day. Refining oil produces methane gas, which can leak out into the atmosphere and is the second largest cause of global warming.

Yadav noted that in urban areas like LA, pipelines and oil wells can have leaks. But even then, “across the board, the natural gas emissions from pipelines, the leaks, have also declined; that was a surprising result for us,” Yadav added.

Methane is important to study not just because of its impact on the global climate but because it absorbs much more energy while it’s in our atmosphere than carbon dioxide. Though it has a shorter lifespan than CO2, methane in the atmosphere is responsible for around 30% of global warming since the pre-industrial era.

Yadav said that it’s not for sure that pipelines are the main source of methane leaks; there’s also livestock operations, landfills, natural gas plants, and refineries that could be responsible. But another JPL device, called EMIT, can help pinpoint specific sources of fugitive emissions. EMIT is an imaging device that was launched to the International Space Station on a SpaceX rocket last July, and it is able to create a map of methane plumes globally from orbit.

A second study authored by JPL researcher Andrew Thorpe and published this March looked specifically at the region’s oil refineries in LA’s South Bay. Both reports could go a long way towards staking public confidence in the varying ways to measure methane emissions.

Thorpe’s study relied on an airborne device developed by JPL called AVIRIS-Next Generation— a device that can be attached to an aircraft and create images of plumes of methane that are normally invisible to the naked eye.

“Everything that we're doing in the California study has an application globally,” Thorpe said. “The thinking is if you can change behavior, that you would expect to see a change in the number of methane plumes observed over a certain country, and the California study indicates that is definitely a possibility.”

Using the AVIRIS-NG device, the JPL surveyed local refineries during the first summer of coronavirus to see if their emission rates were at all affected by the global pandemic. The benchmark for this study was earlier similar surveys conducted in 2016 and 2017.

The device recorded a 73% reduction in methane emissions in 2020 from the earlier surveys. But Thorpe said it’s not accurate to say all this emission reduction came from a COVID slowdown– in fact, oil and natural gas production has been on the decline since 2015, Thorpe noted.

The first version of AVIRIS launched in the 1980s but the current project’s been in use since 2013, when JPL first partnered with the Department of Energy and Chevron to experiment its use for measuring methane. A newer version of the tech is being developed and should be launched within the next six months, Thorpe said.

“Methane is invisible to the human eye, even if you were at the tank and there was a methane plume, you wouldn’t see it,” Thorpe explained. “But there are technologies that can make the invisible visible, and if you can see a gas plume and you can say that it’s coming from a location on the ground, that can lead to mitigation.”

- NASA’s DART Mission Could Lead to Discoveries About the Origins of Our Solar System ›

- NASA’s JPL to Launch Two More Mars Helicopters ›

- Solar Storms Could Cost North America Up To $2.6 trillion. The JPL Is Trying To Predict When They Might Occur ›

- How NASA Satellite Images Could Influence Climate Change Policy ›

- NASA’s JPL Receives Billions to Begin Understanding Our Solar System ›