Are a Vehicle’s Features More Important Than It Being Electric?

David Shultz reports on clean technology and electric vehicles, among other industries, for dot.LA. His writing has appeared in The Atlantic, Outside, Nautilus and many other publications.

The state of California wants 100% of new passenger vehicles sales to be fully electric by 2035. Last year, the state hit a nation-leading 16%. That’s pretty good, but 84% is still a long way to go.

A new study, published Monday in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, investigates which factors have been responsible for the rise in new EV sales nationally. The findings indicate that consumers are increasingly likely to choose an electric vehicle, and nearly all of the gains can be explained simply by improving technologies.

Principally, the researchers tried to tease apart whether improvements in the technology or just plain old consumer preferences have driven EV adoption. Kenneth Gillingham, one of the authors of the new study, said that at the outset, he expected both factors to be working in tandem: As EVs go mainstream, people become more accustomed to them, they ride in them, their friends or family might buy one, while simultaneously, the range, the features, the charging speed all improve and make the case more compelling.

However, the study found that that’s not actually the case. Only the improving tech explained the rise in EV adoption. The result echoes what previous surveys about Tesla have shown: People care less about whether the car is electric and more about what the car can do.

The new study used a survey of potential new car buyers that were recruited online in a nationally-representative sample. Buyers were shown head-to-head comparisons of vehicles, where one was electric and one was not. Both vehicles were identical aesthetically, but differed in their price, powertrain, operating cost, acceleration time, range, fast charging capability, and brand country-of-origin. These traits were randomized, and then the buyers chose which vehicle they preferred. “That's the beauty of this type of exercise,” says Gillingham. “We can keep all the intangibles the same, but focus on differences in things that really matter to people.”

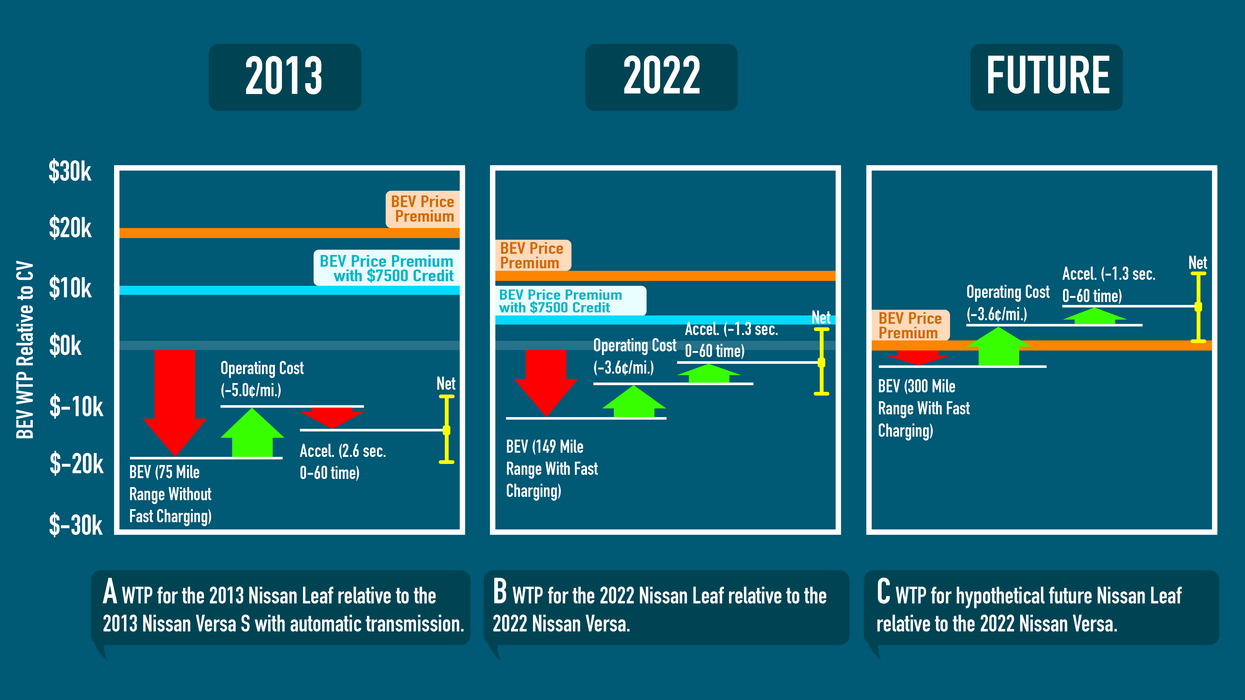

The experiment’s design allowed the researchers to understand how much more buyers were willing to spend on electric cars, and which technologies made the biggest impact on their willingness to pay. Importantly, the researchers could also compare this new data to a similar study conducted in 2013, to gauge how attitudes are changing and make predictions about the future.

Unsurprisingly, the data shows that range remains among buyer’s biggest hang ups when it comes to buying an electric vehicle. For instance, when evaluating the electric 2022 Nissan Leaf, buyers reported that the range of 149 miles–even with fast charging–decreased their willingness to pay by over $10,000 compared to the gasoline-powered 2022 Nissan Versa. In other words, you’d have to knock $10k off the asking price to make the cars equivalent in the eyes of the buyer. However, other features like a lower cost of ownership and a faster acceleration time brought the Leaf almost back to even with the Versa. And if the Leaf’s range increases to 300 miles (which puts it at ~100 miles less than the range of the Versa), as researchers expect in the next several years, the gains in acceleration and cost of ownership suddenly bring the Leaf ahead of its gasoline-powered equivalent.

Those same sorts of patterns played out over and over again in the study, where eventually the tech improves to a point where suddenly the electric vehicle just looks like the better car and buyers make the switch. If technology continues to improve at the current pace and EV costs continue to decline as they have been, the researchers estimate that by 2030, most buyers will choose the EV in a head to head comparison to an equivalent gas-powered car. “If those projections come to bear, it’s entirely feasible that we literally could have half of the new cars and SUVs being electric by 2030,” says Gillingam.

Of course the question is, will the market be able to actually supply enough vehicles to meet that demand. The new study demonstrates just how massive the potential market might be in just seven year’s time. The feasibility of actually getting supply chains in place, manufacturing online, and building enough vehicles to capture that demand, however, remains another question outside the scope of this research. The opportunity is there, though, says Gillingham. “If you are a large automaker, you probably are gonna want to have an electric version of many of your best sellers, given how large the market appears to be.”

- Prediction: EVs Are Disrupting Car Shopping Habits, Giving 3 Companies a Competitive Edge in 2023 ›

- What To Do When Winter Travel Chills Your EV Battery ›

- Which EV Adoption Barriers Actually Matter? ›

David Shultz reports on clean technology and electric vehicles, among other industries, for dot.LA. His writing has appeared in The Atlantic, Outside, Nautilus and many other publications.

Image Source: Skyryse

Image Source: Skyryse

Image Source: Northwood Space

Image Source: Northwood Space